There is a new War on the Rocks article making the rounds on pro-Russian channels as proof that the Ukrainian armed forces are in disarray. Maybe, but I read the article and I find it ridiculous and unhelpful. Keyboard warriors and armchair generals really will believe anything if it confirms their pre-existing biases.

The article in question is a 2 June piece written by Erik Kramer and Paul Schneider, two retired American Green Beret officers, about the (apparently) appalling condition of the Ukrainian command and control (C2) structure. The story is, of course, a sales pitch for their private training initiatives. Which is fine, as a sales pitch isn’t necessarily false or unreliable. However, the incidents detailed in their report are anecdotal, often unrelated to the training product they’re pushing, and at times even directly contradict each other.

Furthermore, I looked up Kramer and Schneider, a fairly obvious step that, apparently, no other “pro-Russia” commentator bothered to do, and the results are interesting. I’ll get more into that in a bit.

This article is a good example of an unreliable an unreliable narrator. The unreliable narrator is a commonly used story-telling device in books and movies, in which a character (typically the protagonist) gives conveys false information to the reader. For example, Patrick Bateman in American Psycho is literally insane, so nothing he says can be trusted.

In the real world, journalists, military men, and academics can convey false information to the public for a variety of reasons. They might be too inexperienced and disconnected from the local culture to understand what’s going on. They might lie deliberately to push a certain agenda or for personal financial benefit. A fourth category of people, the expat, is possibly the most dangerous unreliable narrator. He is often more knowledgeable than foreign journalists and academics, which enables him to construct a more elaborate and convincing lies about his home country to push a certain idea.

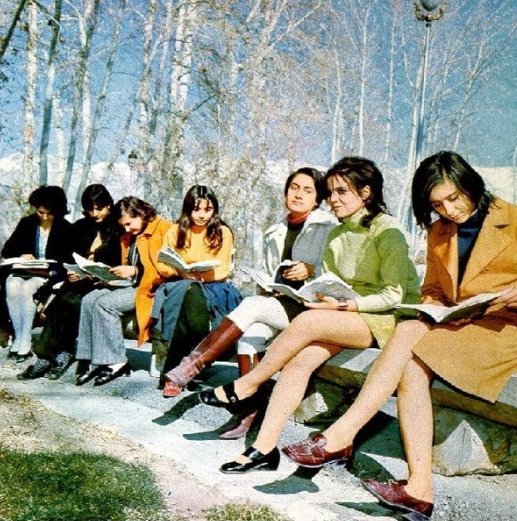

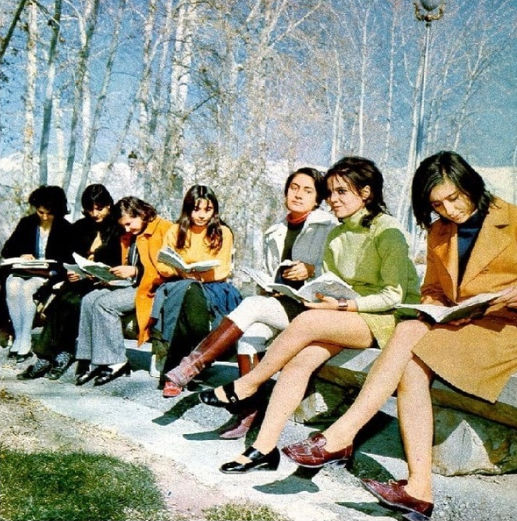

A classic example of the unreliable narrator is what I call the “emancipated woman” myth. The internet is flooded with photos from places like pre-revolution Iran and pre-Taliban Afghanistan, and they all look something like this:

There’s ideological agenda is to push a narrative that all women in these countries in this time frame looked and dressed like well-to do western, which simply isn’t true. The wealthiest, most educated, and liberal people in the capital might have dressed like this in 1970s Kabul or Tehran, but that isn’t necessarily representative at all of the rest of the population. Worse still, when you meet expats from these countries in person, like the famous Iranian dissident Marjane Satrapi, this can further reinforce the false belief that the large majority of people from her country are like this and have the same beliefs.

Judging from these photos, it is easy to understand why revolutions and military defeats always catch the US State Department by surprise. Our experts look at cherry-picked information which seems to prove a certain narrative. The nationalist government of China is winning. We are winning in Vietnam. The Shah’s government is strong. The Afghan government is strong. Chaotic Saigon-style evacuations are the product of an organization that consistently has wrong beliefs, and consequentially always surprised by sudden failure, and is never even adequately prepared for even the possibility of failure. After such a defeat, like the collapse of the Afghan puppet government in the summer of 2021, experts are able to come back to the scene of the crime armed with hindsight, and discover, unpleasantly, that the signs of impending failure were obvious, and were obvious for very long time.

Now we have this Kramer/Schneider article painting a very dismal picture of the Ukrainian armed forces and their ability to fight. That’s very nice for pro-Russia bloggers so they accept it without question. When you know someone is an unreliable narrator, you shouldn’t immediately accept what he’s saying, even when it’s something that confirms your pre-existing biases.

With all that in mind, let’s take a look at this article by Kramer and Schneider and their assessment of Ukrainian military inadequacies. The authors claims include:

Lack of Mission Command

In our experience, across many units and staffs, the Ukrainian Armed Forces do not promote personal initiative and foster mutual trust or mission command. As Michael Kofman and Rob Lee recently discussed on the Russia Contingency podcast, elements of the Ukrainian Armed Forces have an old Soviet mentality that holds most decision-making at more senior levels. Amongst military leaders at the brigade level and below, our impression is that junior officers fear making mistakes. During our training sessions with field grade officers, we are often asked what the punishment is for failure during missions or making bad decisions. We are also repeatedly asked at each step of planning or operations, “Who is allowed to make this decision?” They are surprised that U.S. battalion battle captains (staff officers who oversee ongoing battalion operations) have the authority to make decisions or give orders on behalf of the battalion commander.

Lack of Effective Training

The Ukrainian Armed Forces’ current training philosophy is based on the old Soviet model. Large-scale battalion-level training is orchestrated and choreographed. During several exercises, we witnessed company commanders overseeing the exercise from afar and only occasionally interjecting. They were acting more as observers than direct participants. This philosophy is changing and, as noted in the Russia Contingency, appears to be generational. Younger officers are more open to Western military–style leadership, while older officers have clung to Soviet doctrine. Despite these tendencies, we have yet to see any true combined arms training involving infantry, artillery, and armor working together. Synchronizing all these different elements to achieve maximum military effect, avoid fratricide, and confuse the enemy’s takes repeated training at all levels of command, which allows leaders to make mistakes and work through processes.

Lack of Combined Arms Operations

A critical challenge for the Ukrainian Armed Forces is they do not consistently conduct combined arms operations. The lack of combining synchronized operations results in greater losses of life and equipment as well as failed operations. Based on our discussions with Ukrainian company commanders and our own trainers who fought with the Ukrainian Armed Forces, tanks are used more as mobile artillery and not in combined operations with infantry where the armor goes into action just ahead of the infantry. We have seen firsthand the shot-out barrels of tanks (and artillery) from constantly being fired at max range or overused without maintenance or replacement. Michael Kofman has made similar observations. The armor/infantry relationship is supposed to be symbiotic, but it is not. The result is that infantry will conduct frontal assaults or operate in urban areas without the protection and firepower of tanks. Also, artillery fires are not synchronized with maneuver. Most units do not talk directly to supporting artillery, so there is a delay in call for fire missions. We have been told that units will use runners to send fire missions to artillery batteries because of issues with communications.

Ad Hoc Logistics and Maintenance

Western aid has been critical for Ukraine’s defense. However, the variety of equipment Ukraine now uses has led to significant logistics and maintenance challenges. In our experience, the Ukrainian military cannibalizes new equipment arriving in Ukraine to service equipment deployed in the field. As a result, front-line units only receive a small percentage of what is sent to the country. For example, a .50 caliber machine gun arrives in Ukraine with extra barrels, parts, manuals, and accessories, but by the time it gets to Donbas, all that remains is the gun.

Improperly Used Special Operations Forces

Ukrainian Special Operations Forces (SOF) vary in their abilities, training, and specialties. Unfortunately, many are employed like conventional infantry. This negates the skills that make these units specialized. Due to the high-intensity combat operations and the ongoing Russian counteroffensive, special operations force units are often put in the trenches and not assigned traditional special operations force–type missions of raids, reconnaissance, and ambushes. These piecemeal efforts result in high casualty rates and a lack of special operations force missions involving surprise or stealth that can support and shape battalion and brigade conventional force operations. Traditionally, these types of soldiers receive more training and have less firepower than a conventional unit, so you are wasting a valuable asset that takes time to reconstitute. Ukraine special forces units comprised of international volunteers shop around their services to conventional unit commanders without a mission being tied to a strategic or operational goal. One example of a mission was a conventional brigade commander who had reported to his command that he had occupied a village taken from the Russians. When he realized that the information he had was mistaken and they had stopped short, he asked the international special operations forces unit to go into the occupied village and take a picture of a Ukrainian flag placed on top of a building in the center of the village. Special operations force units are quickly depleted, and replacements lack the training and experience to conduct true special operations force missions.

How to Fix These Problems?

The solutions to these challenges require a reallocation of resources and a change of mentality. This is, arguably, tougher than allocating more resources and spending more money. We recommend a centrally planned, executed at the lower level, synchronized training program focusing on a twenty- to thirty-day training regime for each brigade. This approach is known as a “train the trainer program” and is designed to create a cadre of trainers who then can continue to train new Ukrainian officers that are cycled through the program. The program of instruction should have enough flexibility to make adjustments based on changes on the battlefield and nuances between units. It is critical that this training take place inside Ukraine, using local and foreign instructors for Western and Soviet-origin equipment.

My biggest issue with the article, aside from its shaky and anecdotal basis, is that the problems described seem to be the opposite of what the authors say, and their proposed solution is also the opposite of what should be done.

For example, the authors complain about Ukraine having an inflexible top-down “Soviet” command structure. Aside from the inherent absurdity of accusing an explicitly anti-Soviet ethno state of being too Soviet, this isn’t 1993 or even 2003. It’s 2023. The Soviet Union ended three decades ago, not yesterday. Any senior or even mid-level officer or NCO in the Ukrainian SSR would have retired a long time ago. Then there’s the additional and very obvious fact that the Ukrainian armed forces collapsed in 2014 and had to be rebuilt almost from scratch. The basic building blocks of this new force were right-wing and neo-nazi militias like Azov battalion and the cyborgs. Were they “too Soviet?”

This accusation breaks down even more the longer you think about it, and the authors’ anecdotal examples all seem to prove the opposite. In the opening paragraph of the story, they describe a Ukrainian veteran from Mariupol who incompetently set up his unit to throw grenades and fire machine guns the wrong direction on a training range. That’s an example of too little supervision, not too much. Also, I need to point out that if such an incident happened on a properly managed facility, it could be reported to range control, who would send someone to shut down the training event and punish the person responsible. So, overall, the story doesn’t match the lesson the authors are trying to convey.

Accusations of inflexible top-down command structure also don’t match up with their description of special forces units being misused. An SF commander “shopping around” for assignments is, again, an example of too little supervision, not too much. A case of supply exceeding demand (SF shopping for units that need them rather than the other way around) clear sign that these units don’t have a clear purpose. The statement about SF being “quickly depleted” doesn’t make sense unless SF commanders are deliberately choosing suicide missions, which seems unlikely.

The whole section about lack of mission command makes little sense. For readers who don’t know, “mission command” is the current buzzword for allowing subordinates to take the initiative and have at least some leeway in choosing how to accomplish an assigned goal or objective. Small unit leaders being reluctant to take the initiative can be caused by micromanagement, but in this case it’s much more likely caused by lack of experience and training. This is also pretty obvious survivorship bias at play here. Aggressive leaders tend to be killed while their more cautious peers survive.

“Train the trainer” is the authors’ proposed solution, but it doesn’t really make sense, and for multiple reasons. So essentially, the US armed forces have something called OCTs, Observer Coach Trainers. These are skilled professionals who can teach soldiers, particularly freshly-mobilized reservists, how to correctly perform their jobs in an upcoming deployment. It’s not possible for a handful of experts to train hundreds or thousands of people, so they mentor that unit’s leaders and key personnel, who then pass that knowledge on to everyone else. It is true that a person can be trained to be an OCT in 30 days… if he’s already an expert in his field. OCT certification is about teaching someone the “correct” way to teach, it’s not a magical way to make someone competent at teaching something he himself is unfamiliar with.

When presented with an organization that is under-trained, a solution needs to start at the top and trickle down to the lower ranks. Trying to train random sergeants and platoon commanders is the opposite and has no chance of success. The brutal reality of the matter is that when an organization is already at war, it is too late to try to re-train it.

Some of the article’s complaints make no sense, or at least aren’t related to the supposed topic. For example, this idea that Ukrainians have to send runners to communicate with artillery batteries. I don’t actually believe this story, as it sounds implausible. A person can’t plausibly run or even drive 5-10 kilometers in a timely manner. What’s more likely is that small units, like platoons and companies, have to have to often rely on hand-delivered messages due to a shortage of radios, and the radios they do have are jammed often. The reason I say this information is irrelevant is because it’s a problem that is solved by more funding for equipment, not training.

For a brief tangent, I do find it likely that Ukrainian fire support isn’t responsive and timely enough, and often fires blindly without anyone correcting it. Recently I shared a video of a Russian attack on Ukrainian trenches and this is exactly what happens. Ukrainian artillery, apparently, received orders to fire on the compromised trenches – the problem is that the Russians anticipated this and wait a short distance away while the trench is plastered with shells.

Overall, I find the article too hysterical to be trusted, and this is further confirmed by my research of the authors. They both have special forces backgrounds, and in my experience SF guys are highly knowledgeable and definitely not dumb. They also have almost no online presence, besides LinkedIn profiles and a tiny number of articles written over years, which is typical for SF guys. They’re particularly aware of personal and operational security, so make a habit of not having social media accounts and avoiding photographs. They market themselves through personal networks, and have no need for constantly howling online like a guy trying to sell shitcoin.

For example, I found a 2022 article written by Schneider on the Small Wars Journal. It’s very different in tone from the War on the Rocks article, and he expresses awareness of some of the problems I just expressed, like survivorship bias. I find it difficulty believing he could have awareness of a topic in one year, then suddenly forget about it in the following year. Also, he wrote the Small Wars Journal article after having it reviewed and approved by Army authorities. I find it unlikely he would abandon such caution in Ukraine, which means he got this new article approved as well.

This is why you do your homework kids, and why you should think twice before repeating something as fact.

Ian Kummer

All text in Reading Junkie posts are free to share or republish without permission, and I highly encourage my fellow bloggers to do so. Please be courteous and link back to the original.

I now have a new YouTube channel that I will use to upload videos from my travels around Russia. Expect new content there soon. Please give me a follow here.

Also feel free to connect with me on Quora (I sometimes share unique articles there).

I read it and it seemed to me to be a sales pitch.

Didn’t see it. What exactly, what phrase led you to this conclusion?

It is a sales pitch for this guy’s shitty training company

I like your “Shitcoin” line. They sell kit, tee shirts and coffee too.

The people criticizing the command & control are unaware how much can go wrong in such a heavily contested battle field where all the gear and uplinks are subject to EW measures and confusion. It’s all people who are used to having a complete technological edge on the opponent or clear conditions, something does not hold for the UA combatants.