Last night I read Mumu, an 1852 short story by Ivan Turgenev. If you are not already familiar with Mumu, I would like you to read it first, and there is an English translation available here. As I said, it is short, only 22 pages. If you really don’t want to take my word for it and read the whole thing, the Wikipedia article is here.

Mumu is a short story, so my review will be short. It is possible to over-analyze literature and I think Turgenev’s Mumu is no exception. The tendency to over-analyze gets worse when western critics review things from barbaric lands. What I mean by that is when a foreign culture is “othered,” the experts, or especially the experts, tend to over-fetishize it. An expert who fetishizes the subject matter searches for layers upon layers of meaning that don’t necessarily exist. For the perfect example, look to the 1987 review of Mumu by an Edgar L. Frost. Look, we are talking about a 22-page story. The review of said story should not be 16 pages long.

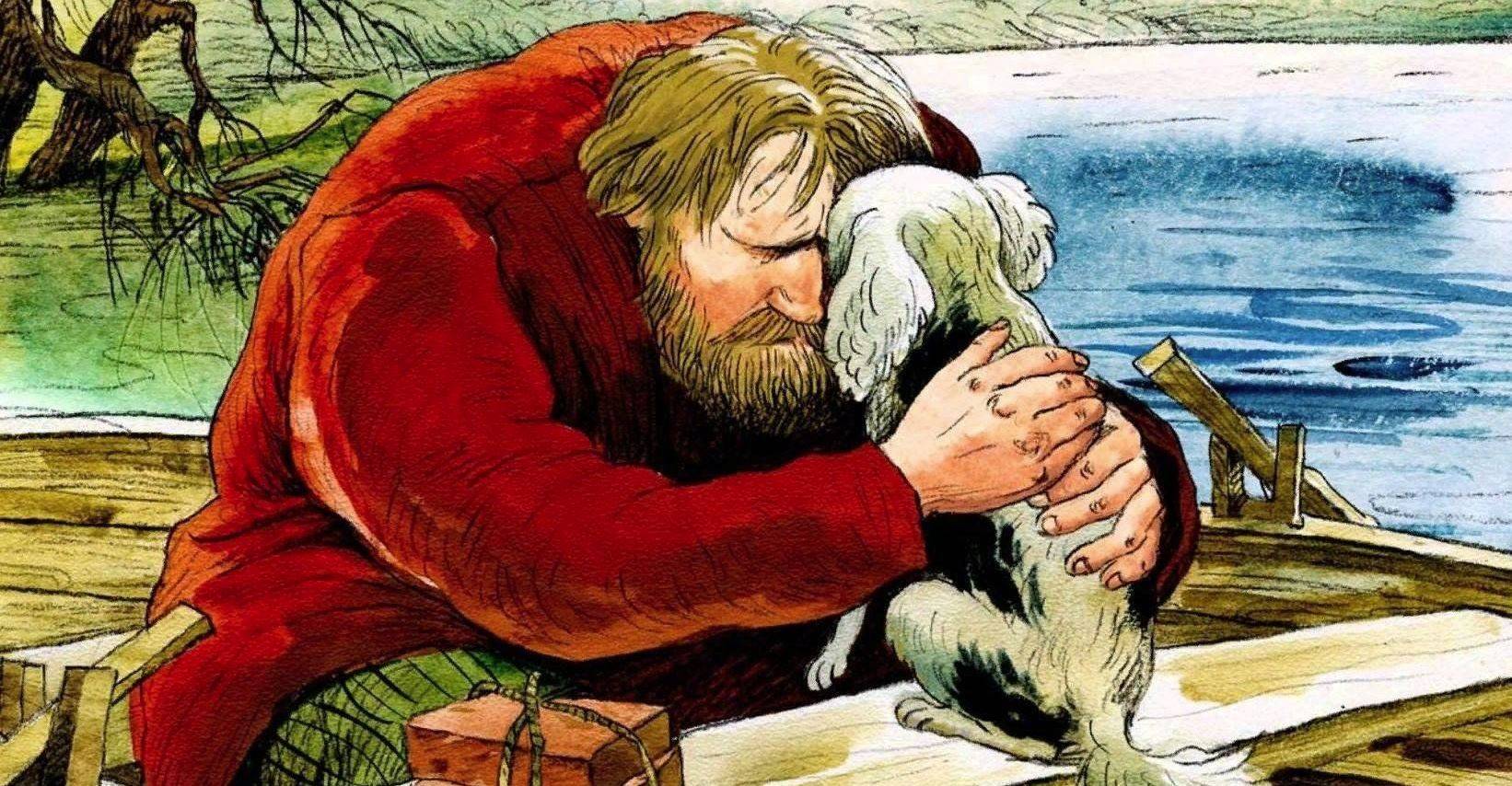

So no, I don’t think Turgenev was making a grandiose statement with many layers of meaning for future readers to uncover through skilled detective work. Mumu is a simple story about a simple man and his dog. Anyway, the interpretation of a story falls upon the reader. So here is my interpretation.

The main character, Gerasim is a giant and strong villager born deaf and mute. Why Turgenev chose to make Gerasim a deaf mute is anyone’s guess, but there wasn’t necessarily any great point here except that people with various disabilities do exist. From reading various reviews and comments, I think Gerasim is one of those characters who is simultaneously overestimated and underestimated. He is completely uneducated and very simple, even more simple than a person who can talk and listen, so it is unfair for the modern reader to demand complex decision-making of him. Yet in the end, Gerasim shows more wisdom than the modern reader typically gives him credit for.

Despite having the strength of four men, he is powerless. Furthermore, Gerasim is a villager living in Moscow. In his old village, Gerasim would be accepted as a great laborer, but in the city he is shunned. Even his failings in winning the affections of the washmaid Tatiana are exaberated by living in the city. His simple but sincere attempts to win her affections could perhaps have worked on a village girl, who might just be glad to have a man who is strong enough to take care of the family, doesn’t drink and probably won’t beat her. Even if he’s not much a conversationalist.

But the bigger problem with Tatiana is the estate owner, the barinya, a cruel old woman who delights in exercising power over everyone in her dominion. The barinya decides to marry Tatiana to Kapiton, a local drunkard. For further context, Tatiana is an extremely shy 28-year-old washmaid with a birthmark on her left cheek. Maybe perfect in Gerasim’s eyes, but to anyone else not exactly a desirable bride. Though neither people are excited about the prospect of marrying each other, they go along with it anyway out of fear. I don’t think the barinya actually had the legal authority to force serfs to marry each other, this was still a Christian country after all. But the ability to punish people gave her the de facto authority whether or not it was formally law. For me, that’s one social lesson from Mumu.The regime stays in power through the willing obedience and collaboration of its subjects. The disobedience of one subject is punished by the other willing subjects. So all of the barinya’s subjects, Tatiana, Gerasim, Kapiton and all the others, follow her instructions even when they’re incredibly wrong and cruel.

Kapiton fears being beaten by a jealous Gerasim, so everyone comes up with a scheme to make the barinya’s orders work. Tatiana pretends to be drunk to make Gerasim disgusted with her and not oppose the marriage. The scheme works.

When Kapiton’s habit of being a useless drunkard becomes too much and he’s exiled along with his wife, with neither of them mentioned again. So why even have this episode in the story at all? The first half of Mumu has almost no apparent impact on the second half, with the girl being immediately replaced by the dog as the object of Gerasim’s affections. So why even include it? Well, I think for two reasons. For one, the marriage scheme illustrates the barinya’s relentlessness, and the equal relentlessness of her followers. And this interpretation hinges on one important moment. When Tatiana is about to leave with her useless husband into exile, Gerasim gives the red handkerchief he had bought her shortly before the marriage scheme, and she cries. Why would he give Tatiana the handkerchief and why would she cry over it? If Gerasim had been disgusted with her, then he should have thrown the gift away, but he kept it. And Tatiana crying that Gerasim loved her doesn’t make sense as an explanation, as she already knew that, and was clearly not in love with him, regardless of her disappointment in Kapiton.

From my perspective, this can only mean that Gerasim had not been fooled but played along with the scheme anyway. At this moment Tatiana understands he hadn’t been fooled is moved by his selflessness. The barinya sees herself as a puppet master, but Gerasim isn’t her puppet. Understanding this is crucial to understanding the second half of the story. But Gerasim’s intentions can only be guessed at. Is he acting submissively like a whipped animal, or defiantly like a lion? Since he is mute and there’s no internal monologue, that’s up to the interpretation of the reader. It was apparently important to Gerasim for Tatiana to know that he wasn’t fooled, which doesn’t seem consistent with someone who was beaten into submission.

Then moments later, Gerasim rescues Mumu from drowning in the river. Everyone reading this should know what happens to Mumu in the end.

So what to make of that?

Well, let’s look at the sequence of events. First, the barinya met Mumu and offered milk and food, which Mumu rejected by backing against the wall and baring her teeth. The barinya wants every living creature in her domain to figuratively or in this case literally eat from her hand, so Mumu’s rejection sealed her fate. She had to be destroyed. First, she ordered Mumu kidnapped. After Gerasim rescued Mumu, he hoped he could keep her safe in his little house, but that hope was dashed when the barinya’s henchmen arrived and demanded the dog. Facing the barinya’s power, Gerasim realizes there is absolutely nothing he can do. He promises the henchmen to get rid of Mumu himself. One of the henchmen, Stepan, is like a kind soldier. He follows orders, but sympathizes with the victims of those orders. Stepan is the one who persuades the barinya and everyone else to trust Gerasim and not interfere.

Then comes what might be one of the saddest scenes in literary history.

Some naysayers insist that Gerasim should have tried to run away or otherwise tried to save Mumu in some way. But the author himself went to fairly long lengths to explain why that wouldn’t work. No matter where Mumu was hidden, the barinya would have eventually found her.

Like with Tatiana, the real question is Gerasim’s intent. Was drowning Mumu an act of submission or defiance? Again, it is absolutely clear that this was defiance. Carrying out the execution himself was the most proactive choice possible, not in any way passive. Then he gathered his things and ran away to the village of his birth (which was still on the barinya’s lands). Giving Tatiana her handkerchief was subtle defiance, then drowning Mumu and running away was outright rebellion.

Why the barinya chose to leave him be is a bit of guesswork, as are Gerasim’s thoughts and how much of this was premeditated. He was a simple guy, so maybe he just could not bear to stay after what he had done. Or maybe it was just that important to him for the barinya to know she hadn’t won. And he did win. the barinya decided that there was nothing more to do to Gerasim and left him be. Then she died and her heirs had more important things to think about.

There is this idea that Russian literature is dark and depressing, but I don’t think that’s a true characterization. Instead, I would say there is self-awareness and a sense of injustice in their culture. Not to say our own classical authors didn’t do this, but we don’t apply the lessons to ourselves or even suggest that our system is unjust.

No one should argue that the events of Mumu are strange after what happened to Peanut the squirrel and his friend, Fred the raccoon, in New York. The authorities raided someone’s house, kidnapped his helpless animals and killed them for no reason except to be cruel and demonstrate their power. The “collective west” sneers at the barbarism of the Russian Empire, and yet modern Russia isn’t the regime executing people’s pets for the fun of it.

Here is my dog 🙂

Ian Kummer

All text in Reading Junkie posts are free to share or republish without permission, and I highly encourage my fellow bloggers to do so. Please be courteous and link back to the original.

I now have a new YouTube channel that I will use to upload videos from my travels around Russia. Expect new content there soon. Please give me a follow here.

Also feel free to connect with me on Quora (I sometimes share unique articles there).

А great review and a great picture of Spazz

Good review.

Thank you for the post

thank you for reading and commenting!