Today I decided to take another look at the fourth phase of Russia’s special military operation (see my post here), which began with the announcement of a referendum in four liberated oblasts of Ukraine, as well as the announcement of a partial mobilization of Russian citizens. As I noted in a previous post, there is a huge amount of propaganda and disinformation coming from pro-NATO outlets, but it’s easy to refute. That said, I think almost everyone is missing the significance of these events, and these misinterpretations could spell global disaster.

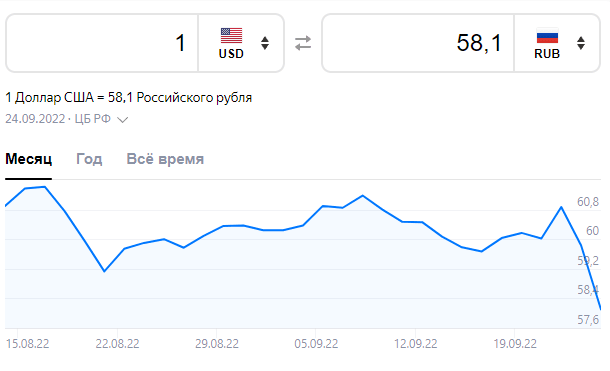

First, I want to, again, address this propaganda that Russian men are “fleeing” the draft. It’s very simple, actually. When people travel, they need money. That’s especially true now that Russian cards no longer work outside the country. This means they have to exchange rubles for dollars or euros. Exchange rates are largely a matter of supply and demand. If huge numbers of Russians suddenly wanted a western country, that would impact the exchange rates and the Ruble would plummet. Well, let’s take a look at the rates as of today:

The Ruble has not plummeted. Compared to the Dollar:

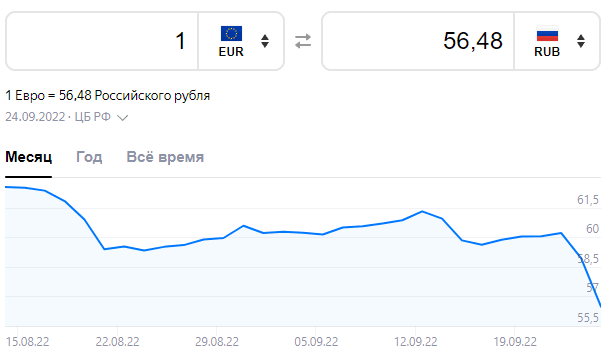

Same with the Euro:

The British Pound has also taken a noticeable dip versus the Ruble:

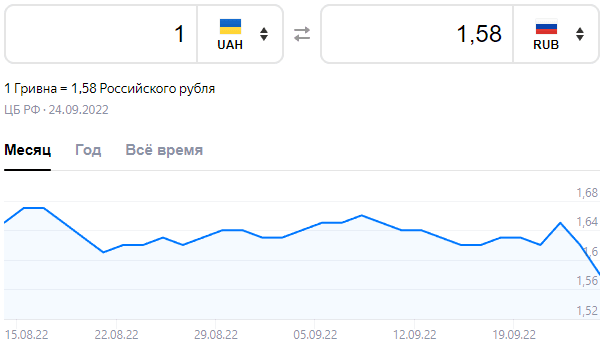

Ukrainian Hyrvania:

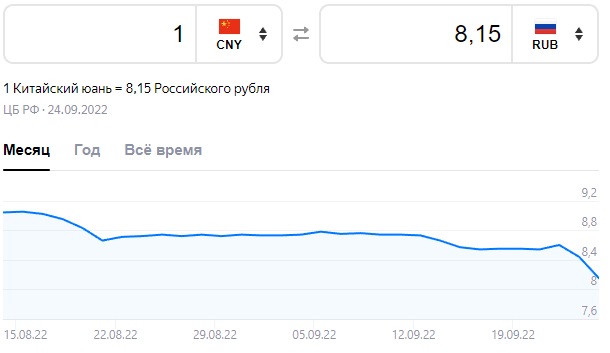

Even the Chinese Yuan:

No mass exodus, sorry. The Ruble just got stronger, which suggests the propaganda about Russia being in “chaos” and “panic” aren’t true and the announcement of a referendum and mobilization to support it were perceived by the market as good news.

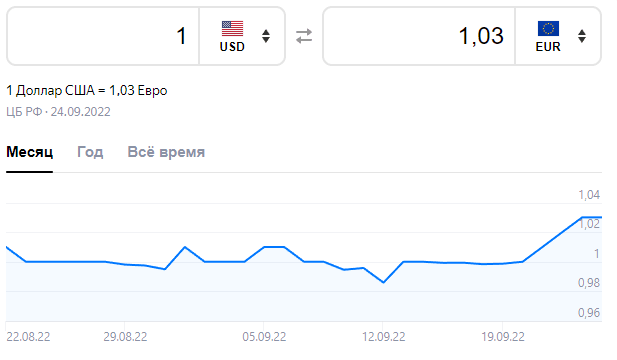

Interestingly, at the same time, the Dollar strengthened. Compare it to the Euro:

The European Union is crumbling, and Biden’s USA is gobbling up the spoils.

Lately I have skimmed mountains of text about recent developments in the Ukraine, both from pro-NATO and “pro-Russia” sources and it is almot all drivel. Look, it’s actually quite simple and anyone even vaguely familiar with military history should be familiar with what’s happening. From the Wikipedia page for “Defense in Depth”

Defence in depth (also known as deep defence or elastic defence) is a military strategy that seeks to delay rather than prevent the advance of an attacker, buying time and causing additional casualties by yielding space. Rather than defeating an attacker with a single, strong defensive line, defence in depth relies on the tendency of an attack to lose momentum over time or as it covers a larger area. A defender can thus yield lightly defended territory in an effort to stress an attacker’s logistics or spread out a numerically superior attacking force. Once an attacker has lost momentum or is forced to spread out to pacify a large area, defensive counter-attacks can be mounted on the attacker’s weak points, with the goal being to cause attrition or drive the attacker back to its original starting position.

A conventional defence strategy would concentrate all military resources at a front line, which, if breached by an attacker, would leave the remaining defenders in danger of being outflanked and surrounded and would leave supply lines, communications, and command vulnerable.

Defence in depth requires that a defender deploy their resources, such as fortifications, field works and military units at and well behind the front line. Although attackers may find it easier to breach the more weakly defended front line, as they advance, they continue to meet resistance. As they penetrate deeper, their flanks become vulnerable, and, should the advance stall, they risk being enveloped.

The defence in depth strategy is particularly effective against attackers who are able to concentrate their forces and attack a small number of places on an extended defensive line.

Defenders that can fall back to a succession of prepared positions can extract a high price from the advancing enemy while themselves avoiding the danger of being overrun or outflanked. Delaying the enemy advance mitigates the attacker’s advantage of surprise and allows time to move defending units to make a defence and to prepare a counter-attack.

A well-planned defence in depth strategy will deploy forces in mutually supportive positions and in appropriate roles. For example, poorly trained troops may be deployed in static defences at the front line, whereas better trained and equipped troops form a mobile reserve [emphasis mine]. Successive layers of defence may use different technologies against various targets; for example, dragon’s teeth might present a challenge for tanks but is easily circumvented by infantry, while another barrier of wire entanglements has the opposite effects on the respective forces. Defence in depth may allow a defender to maximise the defensive possibilities of natural terrain and other advantages.

The disadvantages of defence in depth are that it may be unacceptable for a defender to plan to give ground to an attacker. This may be because vital military or economic resources are close to the front line or because yielding to an enemy is unacceptable for political or cultural reasons. In addition, the continuous retreats that are required by defence in depth require the defender to have a high degree of mobility in order to retreat successfully, and they assume that the defender’s morale will recover from the retreat.

Consider what I have previously written about the Ukrainian armed forces, like in my post The Blood Pump of Donbass:

Ukrainian forces are adequate for static territorial defense, however, they have not shown any signs of largescale maneuvers beyond battalion-sized units.

This has held true even for the Ukrainian offensives this month. See my after action review post here. Ukraine apparently has more than 600,000 soldiers, but most of them are conscripts with little to no training, they lack the expertise, coordination, and hardware to participate in anything more complex than defending trench lines. That said, don’t underestimate them. Large numbers of determined militia in a strong defensive position can push back “superior” troops. However, they have severe limitations, and this has been true throughout human history. In Ancient Greece, city states mustered large militias of brave hoplites armed with long pikes who could grind down an enemy army through attrition and weight of numbers. But these dense hoplite armies were easily outmaneuvered and defeated by professional armies with finer tactics and more defense weapon types, like Roman legionaries. The Roman legions fought in disciplined smaller units, or maniples, who could wheel and maneuver more quickly than a solid block of pikemen, and negotiate terrain more efficiently.

You see this pattern over and over again as human societies evolve in a somewhat cyclical fashion, along with their weapons. During the Renaissance period, European armies once again fought in thick “forests” of pikemen, like the Spanish tercio. This sheer depth (but not “defense in depth!”), through weight of numbers was needed to protect their gunpowder weapons against aggressive cavalry attacks. But thanks to improvements in gunpowder weapons, this tactic too became outdated and replaced by smaller and more flexible formations.

There is a famous story I read as a child about Arnold von Winkelried, a Swiss folk hero in the struggle against the Austrian army in the 1386 Battle of Sempach. The Austrians’ superior pike army was winning against the Swiss rebels and all seemed lost. Then Arnold shouted “make way for liberty!” and deliberately impaled himself on several of the enemy pikes, rendering those weapons useless and allowing his friends to exploit the gap and destroy the entire Austrian army. Incidentally, Soviet soldiers in WWII often did something similar, stuffing themselves into the firing slits of nazi machinegun bunkers, rendering those weapons useless the same way Arnold did with the Austrian pikes. Without their precious machinegun, that entire section of the nazi line could be swarmed with soldiers and defeated.

Even in the Napoleonic period one can see this pattern. Lightly trained troops had to fight in large, dense formations. This made maneuvers simpler and avoided confusion and panic, but at a serious cost. A unit of riflemen marching in a dense block could never project 100% of their firepower in one direction. A battalion of professional soldiers marching in a thin rectangle could move faster, change direction faster, perform complex maneuvers, and project all their weapons at once. Even the famous “squares” Wellington’s soldiers used to fend off Napoleon’s cavalry charges at Waterloo were not solid blocks of soldiers, but hollow squares. This formation would fail immediately if someone got scared and ran away.

This is why I say a deep formation is not an example of defense in depth, but the opposite of defense in depth. A hoplite phalanx, or a trench filled with patriotic militia, relies on peer pressure and a very simple strategy to fend off enemy attacks. But if you take that militia out of the trench and tell them to carry out a pincer movement against an enemy-held village, it’s a disaster. They just don’t have the training and coordination. In a defensive scenario, if you tell them to leave the trench, retreat 30 kilometers, then mount a counter-attack, it’s also a disaster. That Wikipedia article I quoted above is telling the truth, and that’s why Ukraine is using these tactics. They have 600,000 soldiers, far more than what Russia has in the country, but put most of those soldiers directly on the frontlines where the complexity of maneuver warfare is unnecessary, but at the cost of much higher casualties.

Russian contract soldiers have far more training, more equipment, and proportionally more vehicles making them more mobile, so it is unnecessary to employ “not one step back!” tactics. They can rapidly advance, retreat, and reposition as needed and without the worry of confusion and panic spreading.

In May I wrote about the “fatal scale error” of the Ukraine war:

Taking all of this into account, here is my attempt to summarize how to win a battle, or a war.

Expose as much of the enemy force to attrition as possible, and for as long as possible, while minimizing your own force’s exposure to attrition, while still utilizing them 100% at key moments of the operation for the purposes they’re suitable for.

Here’s an analogy. An army is an object that’s fluid and can be molded into any shape, like water. However, the more you do this, the more your army suffers attrition. You dump a bucket of water on the floor and try to mop it up again, you’ll still lose some. And understand that attrition isn’t just combat losses. Ships and planes crash just from cruising around in peacetime. Soldiers roll their ankles, trucks break drown, and equipment wears out whether or not there’s a war on. Any military unit, whether it is a tank battalion or a crew on a warship, will degrade over time unless they are given sufficient time to rest and refit. Think of a battle like a sports game. A team with many fresh players on the bench will probably win against a team that doesn’t.

Ideally, the enemy should be exposed all the way to their rear echelons to disruption by indirect fire and air attacks. Their soldiers should all be on high alert, suffering high rates of attrition from injuries, fatigue, and desertion, but not able to use their weapons to hurt you. Meanwhile, your own army should be exposed to as little combat as possible, and maintaining large reserves. Those reserves can be used for anything, from replacing or reinforcing units actively engaged in combat operations, or opening new fronts at key times and places.

To give some practical examples, if five soldiers can lob mortar rounds into the enemy camp and keep a whole battalion on high alert all night, that’s a success. If the enemy issues a general mobilization and empties their prisons to respond to a small group of paratroopers, that’s a success. Yet at the same time, the enemy should be unable to effectively respond to your main attacks, so they meet little resistance. In a nutshell, the enemy should overreact to your feints and underreact to your main effort.

We have to consider the politics of this war. NATO’s entire position is centered on the premise that Ukrainian Aryan super humans are easily winning against Russian subhuman orcs. If the Ukrainian army gave up 30,000 square kilometers to the Russian “invaders” like the Russian MoD just did, that would be an unacceptable sign of weakness and western voters wouldn’t understand why they’re sacrificing their livelihoods for a lost cause. We also have to accept the pragmatic realism of the situation. The Russians have a vast superiority in firepower. They can give up territory while inflicting massive casualties on the enemy every step of the way until their offensive runs out of steam. Ukrainians don’t have that option. They would just lose territory with nothing to show for it, and that would have predictable consequences for morale and international support. Ukrainian/NATO tactics work, but come at a cost.

Let’s take a look at Shoigu’s statement on casualties on both sides as of 21 September. From RT:

The Russian military has lost almost 6,000 troops during the fighting in Ukraine, Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu said on Wednesday.

Fatalities on the Ukrainian side are ten times higher, with 61,207 Kiev troops killed, according to the minister.

It’s the first time that Russia announced its losses during the military operation since late March when the number of killed servicemen stood at 1,351, according to the defense ministry.

“Our losses to date are 5,937 dead,” Shoigu revealed.

He also praised the work of military medics, saying that 90% of the Russian troops who had been wounded during fighting were able to return to action after treatment.

“Initially, the Armed Forces of Ukraine amounted to between 201,000 and 202,000 people, and since then they have suffered losses of around 100,000, with 61,207 killed and 49,368 others wounded,” he said.

Shoigu added that Kiev has since mobilized hundreds of thousands more men into its forces.

The Russian forces and the militias of the People’s Republics of Donetsk and Lugansk have also eliminated more than 2,000 mercenaries fighting for Kiev, the minister said. Just over 1,000 foreigners currently remain in the ranks of the Ukrainian military, he added.

I feel the need to add some clarifications. First, Shoigu was just talking about losses of the Russian armed forces, not the allied separatists, who have apparently taken significant losses too. As for his statement on Ukrainian losses, those figures of killed/wounded are based on however the Russian MoD confirms enemy casualties. That methodology is important because it determines how soldiers and commanders are awarded and otherwise distinguished for their battlefield accomplishments. So his figures are probably reliable, but they are also probably an understatement. Russian observers and drones often can’t know for sure how many enemies were killed in an artillery barrage or a missile strike. Their ability to confirm kills is certainly even lower when it comes to strikes deep behind enemy lines. Rumors of Ukrainian killed in action exceeding 70,000 or even 80,000 are likely, based on Shoigu’s estimate, probably true.

His count of 49,368 Ukrainian wounded seems very low compared to 61,207 killed, since in modern wars the number of wounded tends to have a 3:1 or 4:1 ratio with fatalities. This is a guess on my part, but I think he was most likely referring to Ukraine’s overall irrecoverable losses (minus prisoners). A little over 60,000 killed Ukrainian soldiers would suggest at least 180,000 wounded, of which a little over 49 thousand could not return to duty. Based on Shoigu’s claim that 90% of Russian wounded have returned to duty, if there were 18 thousand wounded, roughly 1,800 could not return to duty. Of course that’s a total guess since the Russian MoD to my knowledge has not made any kind of statement on numbers of their wounded.

Shoigu’s statement on mercenaries is equally interesting. If accurate, that means as of 21 September, there were only 1,000 foreign mercenaries fighting alongside the Ukrainian armed forces. Since then, they have taken further heavy losses. From RT:

Up to 300 foreigners fighting for Kiev against Moscow have been killed in Nikolayev Region in southern Ukraine, the Russian Defense Ministry said on Saturday.

“Up to 300 militants were eliminated by a missile attack on the point of temporary deployment of foreign mercenaries in the area of the village of Kalinovka, Nikolayev Region,” the ministry’s spokesman, Lieutenant General Igor Konashenkov, announced during his daily briefing.

This adds to a growing list of foreign combatants who have lost their lives fighting for Ukraine. Earlier this week, Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu revealed that Russian forces and the militias of the Donbass republics had eliminated more than 2,000 foreign mercenaries. As of September 21, 1,000 foreigners remained in the ranks of the Ukrainian military, according to the minister, whereas in April the number was estimated at 3,000.

The “fog of war” is real and it can be tough to tell what exactly is going on in Ukraine, but the number of foreign mercenaries is a decent indicator for which way the tide is going. There are millions upon millions of combat veterans in NATO countries. Why aren’t more of them going to fight? There are two possibilities, which are not mutually exclusive:

-The war is a bloodbath, and foreign mercenaries just don’t have a dog in the fight so aren’t interested.

-Ukrainians and foreign mercenaries don’t get along.

I’ve seen pretty substantive chatter that both of these statements are true.

Now, about the mobilization. To understand the purpose of the mobilization, we need to understand “defense in depth,” which I’ll get into momentarily. From RT:

Russia will call on 300,000 reservists to serve in the conflict with Ukraine, under a partial nationwide mobilization, Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu announced on Wednesday. He added that Moscow has considerable capacity in terms of personnel.

According to Shoigu, the mobilization will apply neither to university students, nor conscripts. The minister stressed that only those who have already served in the military will be called up.

“Those are not people who have never heard anything about the army. Those are those who, firstly, had completed their military service, secondly, those who have a military specialty… and have military experience,” he noted...

The defense minister noted that the line of contact between Moscow and Ukraine’s forces is more than 1,000 km long, and the mobilization would be used for defending it.

“It is natural that this line should be reinforced and those territories (held by Russia) should be controlled. Of course, this is the purpose of this work,” he said, referring to the mobilization effort.

Details of an unpublished clause contained in the decree on partial mobilization are for “internal use” only, Kremlin Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov said on Wednesday.

He added that the information contained in the section relates to the number of personnel to be called up, but did not elaborate any further.

Partial mobilization in Russia was announced by President Vladimir Putin during a televised address earlier on Wednesday, and the relevant decree was later published online. The document consisted of ten clauses, but one of them – No.7 – was not disclosed.

“It’s for internal use, and that’s why I can’t reveal it,” Peskov said after being asked to comment on the matter.

“The only thing I can tell you… is that Sergey Shoigu in his interview spoke about 300,000 people, [who are to be mobilized.] The talk is about 300,000 people. And, as the defense minister clarified, they won’t be recruited simultaneously,” he pointed out.

My observations:

While the explicitly stated purpose of the mobilization is to strengthen the defensive line between the liberated oblasts and Kiev’s forces, this doesn’t mean all of the call-up soldiers will be sent. It’s possible that some of these reservists are technicians and professionals who will beef up Russia’s defense sector, and this doesn’t necessarily entail leaving the country at all.

They will be called up in waves, which means the Russian MoD came up with this 300,000 figure as the strength they would need to two or more full rotations.

Beyond that, it’s hard to say much else about their mobilization without straying into complete conjecture. Of course the Russian MoD is being deliberately vague, and no western writer or analyst seems to want to seriously know what’s going on, and just spews silly propaganda instead. So, I’m left with conjecture. I think I’m probably on the mark, but take this with a grain of salt as usual.

Some of these reservists could be deployed as replacements, but most of the units currently in the Ukraine theater don’t seem to have taken particularly heavy losses. Reservists could also be sent as individual or small-unit replacements, allowing contract soldiers to rest and recuperate. This system has the added benefit of requiring little to no further commitments in equipment, since a soldier obviously doesn’t take his tank when he goes on leave, it’s given to the soldier who replaces him. However, that’s still not enough of an explanation since the explicitly stated purpose of the mobilization is to strengthen the forward line of troops. This implies the creation of new units, which is much more complicated. These new soldiers need staffs of experienced officers and noncommissioned officers to fall in on.

Based on the Russian system of drawing manpower and equipment from their brigades to create temporary battalion tactical groups, this is my guess for what they’ll do with the new reservists. They’ll draw more existing battalion staffs and company command teams and give them reservists as the bulk of the rank-and-file soldiers. And I don’t see anything that would prevent them from reassigning contract soldiers to mentor the inexperienced reservists.

Consider where these units will be sent. When the first rotation of, say, 100 or 150 thousand reservists arrives, that frees up the more experienced contract soldiers to be concentrated in crucial areas of the front.

Also consider the principle of defense in depth.

We should start seeing the first reservists enter the Ukraine conflict in 2-3 months. Maybe as soon as six weeks.

Ultimately, here’s my biggest concern about the media buzz lately. It’s once again the famous journalism blunder “wet streets cause rain,” confusing cause and effect. Russia’s partial mobilization is an effect of the referendum in the separatist regions of Ukraine. The referendum is a much bigger story, and it goes far beyond the 300,000 reservists. By accepting these Ukrainian oblasts into the Russian Federation, Russia puts their reputation on the line. They cannot allow NATO to casually kill civilians on Russian soil without responding. That’s a consequence of the past 6+ months of propaganda. The drones in the West don’t consider Russia a threat, and have become too comfortable with the Ukrainians’ status as proxies. NATO weapons being used against Russian soil would be nothing less than a direct NATO attack against Russia, and we have to assume that it would be treated as such.

Ian Kummer

Support my work by making a contribution through Boosty

All text in Reading Junkie posts are free to share or republish without permission, and I highly encourage my fellow bloggers to do so. Please be courteous and link back to the original.

I now have a new YouTube channel that I will use to upload videos from my travels around Russia. Expect new content there soon. Please give me a follow here.

Also feel free to connect with me on Quora (I sometimes share unique articles there).

Thanks. Long but good read.

One of the possibilities for the utilization of reserves left unmentioned is that they can relieve units that are stationed elsewhere, away from the theatre, freeing up professionals for the conflict.

Well yes, as I said, that is a likely way for the new reservist units to be used.

Thanks for the Military Science lessons Ian.

I’m glad you liked it!

“west streets cause rain” typo in the last paragraph

Great catch, and I fixed it. Thank you!