Chinese Mandarins, American Knights: Law and the Matrix of Values Development

As important as the values of a nation are, equally significant is the mechanism by which they evolve. In this section, we will examine the different matrices of values development in the United States and China. More specifically, we will consider them within the context of the law, their history of development, how they shape the progression of values in each country, and the strengths and weaknesses of each system in a world of ever-accelerating change.

We must begin by defining a matrix of values development. A matrix of values development encompasses both the informal and formal systems by which the values of a people are advanced in a general sense and adapted and applied to a specific time and context. The matrix both shapes the values of a people and has values of its own.

This last point might seem a bit confusing to those who are unfamiliar with the sausage-making process that is the creation of laws and policies, but even for them, it is easy to understand with an explanation. Within any regulatory system of complexity, there are rules and there are rules about how the rules are made. These interrelate. In an absolute monarchy, one in which the highest value is obedience to the supreme sovereign, the rulemaking process is simple: Whatever the king or queen says immediately becomes law. So let it be written, so let it be done. Depending upon the relationship between the state (which is either the property of the ruler or an extension of him) and the faith of the people, these commandments may take on a religious significance greater than their legal one. In a pure democracy, there will be a procedure for making a proposal, debating the proposal, taking a vote, and (probably) recording the vote before a law is implemented. The laws are less likely to take on a religious or moral significance than they are to reflect the moral and religious beliefs of the people at the time.

A matrix of values development encompasses both the informal and formal systems by which the values of a people are advanced in a general sense and adapted and applied to a specific time and context. The matrix both shapes the values of a people and has values of its own.

The procedural rules thus described reflect and shape the values of the society in which they exist, be those values absolutist, theocratic, democratic, or something else. And these rules are a part of the larger matrix of values development. The matrix also encompasses the people who make the rules, the environment in which they work, the hierarchy of rules and rule makers (with not all rules and rule makers being equal), and the public’s perception of/investment in said rules.

As will be established in this section, China is not (nor has it been for centuries, with the possible exception of Mao’s reign) an absolute monarchy. This holds despite the emperor’s historical claims to the Mandate of Heaven, which was never unconditional and could be lost through bad governance. And the United States is not a democracy in practice. Rather, China’s governance and matrix of values development is consensus-seeking and mandarin. America’s matrix of values development is adversarial and medieval.

A note before we continue: Laws and values are treated as being harmonious and synonymous (in the main) in this section. This is not a matter of ill-considered conflation. Rather, it is entirely intentional. Laws and values may differ, but not by too much or for too long. If they do, either the laws will be ignored, the people and the government will be in contention, or the values of the people will change. The focus of this section is on the law, but the theories herein are more broadly applicable to American and Chinese culture and matrices of values development—a point we will briefly consider in a popular culture context.

In failed states and banana republics, the law may be little more than theoretical—something to be dismissed or overcome through bribery—but neither the United States nor China is a banana republic (at present). They, both the United States and China, may enforce their laws inconsistently, but by and large, their governments and their people are closely and proudly (if imperfectly) bound to their respective national values, identities, and myths.

Now, we consider the core of the American matrix of values development—that of our medieval court system.

The expansiveness and power of American courts are noteworthy. America is not the most litigious country, a distinction that belongs to Germany. Nor does it have the greatest number of lawyers per capita—that nation would be . . . Israel. Yet a purely quantitative review of the legal system in the United States fails to capture the importance of the courts in determining the direction of the nation. This considerable power of the courts is exercised through two means—case law and constitutional review.

The common law system (also called the case law system), in which judges can create laws by way of judicial opinion and decisions, is not universal. And it stands in stark contrast to one of its major competitors—the legal system established by the Napoleonic Code, in which laws are created almost exclusively by statute. The common law system is older, deriving from the English tradition of the monarch or his subordinates deciding cases as they saw fit. The Napoleonic Code is a radical revision (implemented under the guidance of Napoleon I) of the earlier civil code of France, with the power of the courts and the upper classes they represented being greatly lessened.

The fundamental difference between these systems is that of induction versus deduction. The common law is inductive: A decision from a particular case is applied to other cases that are analogous by degree (such is reliance on legal precedent or case law, meaning law developed from settled cases). The courts work, often in theory more than practice, towards the development and refinement of universal legal principles. The Napoleonic Code—the model for much European and South American law—is deductive: The law is defined and codified by the legislative branch and applied to individual cases, with precedent having little weight. In practice, neither system is pure. American and English courts enforce statutes, some of which greatly curtail the discretion of the courts. And precedent is not entirely disregarded in the Napoleonic Code countries, but its authority is more often persuasive than binding. Nevertheless, the distinction between the two is still of quite some import. (And yes, one could argue using a different line of reasoning that Napoleonic Code is inductive and the common law is deductive, but we are thinking as lawyers in this section. Let us acknowledge that there is a counterargument for every argument, pick a side, and do the best we can for our clients, billable hours permitting.)

The great strength (and weakness) of the common law is that it relies on specifics. Many cases may be so similar that they are functionally interchangeable (there are a finite number of ways to shoplift from a Walmart), but a significant minority do not. And this is where the threads of legal reasoning tangle. Cases stand to be appealed on either procedural grounds or grounds of legal interpretation. Procedural appeals occur in cases of every sort. Improper admission or rejection of evidence, problems with jury selection, and (in criminal trials) failure by a prosecutor to disclose exculpatory evidence or the defendant not being afforded effective assistance of counsel are all common grounds for appeal. But in the matter of novel cases, there is the additional question of what precedent or guiding principle applies.

Most common law systems suffer from serious inefficiencies and inconsistencies. For example, the Indian court system—established under British rule—is famously backlogged, with at least one case being entered in 1800 and remaining unresolved as of 2019. But even amongst common law nations, the American judiciary plays a distinctively powerful role that contributes to the intricacies of our matrix of values development and makes for a legal system that is inimitably boggling.

This is where the history of the United States Supreme Court and one of its most famous decisions come into play.

The United States Constitution has less to say about the courts than one might think. The structure of federal district and appeals courts (“inferior courts”) is undefined, as is the number of judges to be appointed to the Supreme Court. While the jurisdiction of the federal courts is described expansively, addressing “all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution,” the role of the Court as an active interpreter of the Constitution was never stated or clearly articulated. This role was not established by United States Congress nor the Constitution, but by the Court itself. Before Marbury v. Madison, an 1803 case regarding an end-of-presidential term appointment of a federal judge, the role of the Court was restricted to that of trying cases and reviewing appeals. It sometimes determined if the lower courts were abiding by statutes and the Constitution, but it did not declare laws invalid. This ability of the Court to function above the legislature, effectively becoming a lawmaking (and lawbreaking, if you will) entity as much as a case-deciding one, was the work of Chief Justice John Marshall.

A growing number of nations—Spain, Germany, and Greece, amongst others—have constitutional courts, but none predate that of the United States or share the same degree of worldwide notoriety. Furthermore, the authority of the United States Circuit Courts of Appeals to establish precedent specific to their jurisdiction, and the existence of state supreme courts, which evaluate statutes according to their own criteria, adds layers of complexity.

The effect of this complex system of distinct and sometimes overlapping jurisdictions and constitutional interpretations is to make governance in the United States resemble that of the Holy Roman Empire, a land with one emperor, but many kings. And as the power of the courts grows, the system becomes more medieval, not less.

Professor Robert A. Kagan analyzed the role of courts (the appeals and supreme courts included) in American life, describing our governance as being one of adversarial legalism. This model is not necessarily the most legalistic, most legislated, or most restrictive. Other nations may have considerably more (and stricter) laws on anything from product labeling to assault to environmental regulations and laws on recycling. The difference is in the degree to which the courts and lawsuits brought by private parties can transform policy. Activist attorneys—those who seek to expand concepts of liberty in ways never envisioned by the Founders, to greatly limit the rights of businesses to high and fire employees, and to redefine basic concepts of identity—have had considerable success. They have persuaded the courts to radically reinterpret both the United States Constitution and federal statutes a great many times.

Within this profoundly anachronistic legal system and matrix of values development, change is made not by democratic politicking or technocratic adjustment, but by pleading at the court of the relevant sovereign. Not every decision in America is made this way. In addition to the state and federal legislatures, certain established bureaucracies are large and powerful, with rules and rulemaking procedures of their own. But our point stands in a general sense. And that state (but not federal) judges are often elected, does not negate the feudal nature of the courts. The Holy Roman Emperor was elected as well, and the incumbent advantage of judges is so great as to give them what amounts to lifetime appointments.

Within the framework of adversarial legalism, attorneys are not mere advocates for clients, they are knights jousting before an audience of lords and commoners.

The judiciary and its many fiefdoms hang above every other social system—from schools to businesses to all points in between. The adversarial legalism described by Kagan shapes not only our legal interactions, but our social, business, and personal ones.

Within the framework of adversarial legalism, attorneys are not mere advocates for clients, they are knights jousting before an audience of lords and commoners.

Much of this fighting is mercenary, fame-seeking, or some admixture of the two, but to assume that greed or narcissism is the sole motive energy for members of the legal profession is to deny evidence to the contrary. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) historically (if not presently) took defense of the First Amendment seriously, as did its attorneys, even when they strongly opposed the beliefs of those they were defending. Probably the best known of these cases was National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie. In this legal drama, a Jewish ACLU attorney, David Goldberger, argued for and won the right of neo-Nazis to march through a community in which a considerable number of Holocaust victims lived. (The organizer of the march eventually agreed to move the event to Chicago, where it occurred with little violence.) Jokes about even Nazis wanting their legal representation to be kosher aside, the case demonstrated adherence to principles over convenience, self-interest, or fortune. Goldberger did achieve notoriety, but much of it took the form of infamy, with Goldberger finding himself both the subject of considerable public criticism and—as one might anticipate—less-than-welcome at his local synagogue.

Brown v. Board of Education (ending school segregation), Miranda v. Arizona (of Miranda rights fame), Roe v. Wade (abortion rights, amongst other things), District of Columbia v. Heller (right to bear arms), Obergefell v. Hodges (right to marriage for same-sex partners)—The fact that average American can recognize (if not fully understand the ramifications of) at least a few of these case is noteworthy. The courts, originally intended as the weakest branch of government, have become the coercive social-engineering engine of both first and last resort.

The defining element of legal adversarialism (and the American matrix of values development of which it is a part) is its promotion of courtly combat. It holds the argument, the performative fight, and the power of persuasion as the best and most efficient tools by which social norms and values should be developed and imposed. And he who won the argument becomes the most relevant truth.

As power concentrates within the judiciary and quasi-judicial structures, the stakes of argument and adversarialism increase, as do the intensity, prevalence, and sophistication of adversarial tactics. Evolutionary pressure forces each iteration of amateur and professional advocates to perform better than the last, whose techniques have been widely disseminated. At worst, passion, meaning opinionatedness and bellicosity, may grow to be seen as inherent goods, irrespective of their utility.

The super-prioritization of either consensus or combat can lead to a deviation from what C.S. Lewis called “natural values,” which he tied to the Dao (as interpreted through his personal religious beliefs), and by extension, constructal law. A minority of great conviction, regardless of the truthfulness of those convictions, may prevail over those whose understandings of the world are grounded in reality but who are less inclined to fight for what they see as being self-evident truths.

This bloodthirstiness, with all its love of winning and desperate fear of loss—eat or be eaten whenever you open your mouth—is both part and parcel of the omnipredatorial culture and an active driver of it.

Conversely, deviation from the Dao resulting from a desire for consensus results in errors of a different sort—those bending towards the unexamined assumptions of the quiet majority and the most conservative of philosophers. It may also lead to competitive compliance, an example of which can be found in the focus on testing within China. Other examples present themselves in every part of life.

Consider beauty (and the lack thereof).

Matrices of values development are recursive in that they are both self-referential and can, more or less fractally, repeat across scale. Most of this section addresses matrices of values development within the legal and bureaucratic context, but their mechanisms of operation apply throughout the society into which they are integrated.

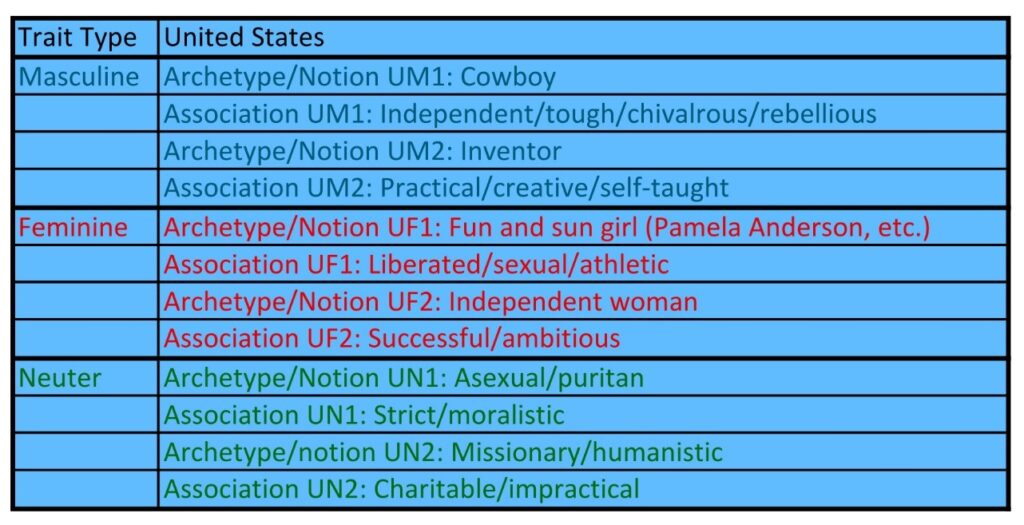

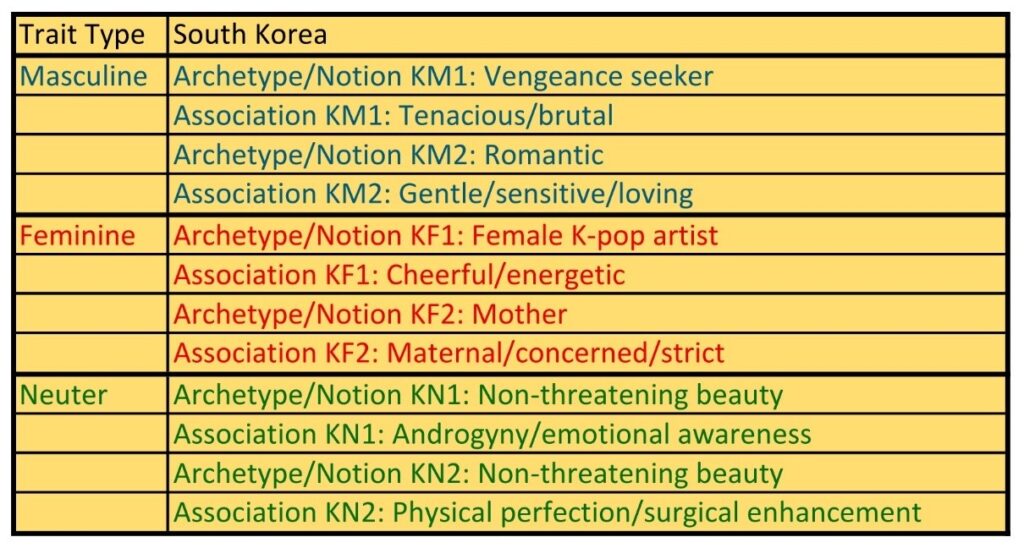

In South Korea, a nation strongly influenced by Ruism and consensus-seeking (and thus an adequate proxy for China in this argument), plastic surgery intended to reduce one’s aesthetic flaws and produce a uniform appearance of attractiveness is ubiquitous. Per capita, the South Koreans spend more on cosmetic procedures than the people of any other nation. Nearly a third of women between the ages of 19 and 29 report having undergone at least one such operation. Stated simply, Koreans, the women most of all, are competitive in the realm of appearance.

And then there is the American opposite of this—body positivity, which attacks the very notion of aesthetics. The body positivity movement was started independently by two different agents—an engineer in New York distressed at how those around him treated his overweight wife and Fat Underground. The latter was a feminist organization in California that produced a manifesto demanding equal rights for the obese (with the underlying assumption being that the obese did not already have equal rights) and declaring the weight-loss industry an enemy.

These competing strategies to address the matter of one’s social acceptance or rejection based on appearance are exemplars of their respective culture’s matrix of values development in action. Within the consensus/Confucian matrix, one strives for victory by achieving excellence in conformity. Within the adversarial matrix, one strives for victory by arguing against the standard one determines to be unfavorable. The Morlocks do not trundle to the courthouse nor do the Eloi flit to the mandarin’s chambers, yet they respond to social pressures just as one would expect, relying upon the tools their cultures afford them.

In the consensus matrix, the majority preference—for beauty, in this case—is the dominant force. In the adversarial matrix, a vocal minority—those who argue that the many should rid themselves of their natural and evolutionarily essential partiality for prettiness—hold sway.

In both instances, there is a ratcheting effect that will eventually lead to absurd outcomes. Korean physical standards become iteratively more particular and difficult to meet. And American demands for fat acceptance, well fed by their many successes, gain mass by the day. Within a few generations, one can imagine Korean technology advancing under market pressure to the level of providing complete face replacement and genetic engineering to reduce the odds of one’s offspring being unattractive. Such procedures and enhancements stand to be cripplingly expensive. Americans, on the other hand, are likely to be rhetorically strongarmed into such uncritical acceptance of the ungroomed and unhealthy that People of Walmart is decried as promoting unrealistic and misogynistic pictures of perfect pulchritude. Thus, every Harrison Bergeron will find himself weighed down and masked in the name of equality and emotional safety.

The direction of the value amplification—be it either in favor of conventional and conformist attractiveness or for the abolition of beauty as a recognized construct—is determined by the rules of the matrix of values development. Without some governing system, either matrix of value development may self-destruct under the pressures of modernity, but the failure mode and output vary according to matrix dynamics.

With that critical bit of context in mind, we turn to the Chinese matrix of values development—its Confucian, mandarin-driven courts, body of traditional statutes, and bureaucracy.

The law within China has a different genesis, a different role, and different history than that of anything in the West. Early Chinese law was distinctly non-Western and placed more emphasis on the maintenance of social harmony and fulfillment of duty according to Confucian principles than on individual rights in the decontextualized, abstract sense. And the family, not the individual, is regarded as the foundation of society. This is not to say that Chinese law did not practically take into account individual concerns or the circumstances in which a crime was committed. The Chinese courts could and did address such concerns, and we will consider the mechanisms by which they did so.

For the sake of our examination, the Chinese courts have been defined by two unique characteristics. The first is that their judges were not professionals dedicated to the practice of law. They were mandarins, educated in Confucian values and social theory generally, but not as attorneys per se. The second is that the courts have had (and still have) little autonomy to change the fundamental nature of law. They were (and are) an organic part of the larger system of government, serving as subordinate to the sovereign, the larger bureaucracy, and the abstract social good.

From the beginning of the mandarinate to 1995, there was no dedicated preparation system for judges. During the Qing dynasty, most adjudications and investigations were performed by local magistrates. These magistrates were responsible for tax collection, education, religious rituals, and other civil and military functions within their districts. They had no training in the niceties of the law. A given magistrate might have had a secretary or assistant knowledgeable in the Qing legal code to guide and advise him, but such was not required by statute or custom.

This does not establish that the Qing system of justice was one of hanging judges and drumhead trials. There was a considerable system of case evaluation during the Qing dynasty, with the provincial governor trying capital cases and being able to examine and modify any lower-court decisions in his jurisdiction (much like an appeals or circuit court). The Ministry of Punishment served as another check against injustice and reviewed all death sentences, which could either be implemented quickly or after an additional mandatory review during the annual Autumn Court, during which the most serious cases were examined. Finally, the emperor had final authority to accept or adjust sentences as he saw fit, including granting clemency—a power not unlike that of the state and federal chief executives.

Despite this extensive formalization of legal procedures, the system remained resistant to professionalization, with the practice of law being effectively criminalized during much of the Qing dynasty and the nation having no law schools until 1904.

Forbidding attorneys in a court may seem strange practice to those from the United States, a nation where the advertisement of legal services has become an art form. But one should not attribute this restriction to some desire of the emperor to rule unencumbered by the loquaciousness of learned legal minds. Rather, it reflects the thinking of Confucius himself, who saw the law as a weak and imperfect tool of leadership, inferior to that of guidance by example. Had the Chinese Legalist school of thought—one more cynical in its view of human nature and more concerned with controlling behavior than in cultivating morality—prevailed, the Chinese legal code and systems of governance might have looked quite different.

The Master said, “If the people be led by laws, and uniformity sought to be given them by punishments, they will try to avoid the punishment, but have no sense of shame. If they be led by virtue, and uniformity sought to be given them by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of shame, and moreover will become good.”

Confucius

The lack of professional attorneys and judges and the Confucian skepticism of the power of law did not lead to an underdeveloped body of statutes. And it did not result in incompetent or unnuanced results in a time during which family and social relationships were complex, relatively static, and far more critical to the maintenance of an orderly society than they are today.

A defining element of the Confucian-influenced legal tradition was that it was a respecter of social rank and propriety. The relationship and social distinctions between accused and victim were often taken into account. A review of the Great Qing Code—which addressed matters civil, criminal, military, and governmental—reveals how carefully complex social and family obligations and hierarchies and the maintenance of societal and family harmony were enshrined in law. And the competing interests addressed in the Code gave the mandarin prosecutor-investigator-judge much to consider when handing down verdicts and punishments.

While some of these regulations related to social station, many of them were not so much classist as they were familial, intended to maintain the Confucian ideal of a family in which every member contributed to the common good. Thus, one would receive a lesser punishment for stealing from relatives than he would for stealing from strangers, with the underlying duty of families to care for and assist their relations seen as a mitigating factor to the crime. According to related theories of responsibility, one would receive a greater punishment for causing injury or offense to a family member to whom one was categorically subordinate.

An interesting example of the capacity of the mandarinate/judiciary to weigh these pieties and concerns and to develop compromise punishments can be found in the Case of Woman Xie.

In Xie, the father-in-law of the case’s eponym attempted to rape her while her husband was away at work. Xie rebuffed her father-in-law’s unwanted advances by liberating the offending organ with a blade, which resulted in his (and presumably his organ’s) death. Xie was thereafter detained and tried.

When deciding on an appropriate sanction for Xie, the government faced the complex issue of how to consider several competing statutes and legal theories. First, there was the matter of an attempted sexual assault, for which the assailant (had he survived) would have received a punishment of 100 strokes of a heavy bamboo cane and exile 3,000 li (about 930 miles) from home. The second part of this sentence—exile—may seem trivial to modern Americans. But it was a serious penalty in an era in which local relationships and family were important and a trip of nearly 1,000 miles was more challenging than the few days’ road trip of present. Had the assault been completed, the father-in-law (again, had he survived) would have faced death by strangulation (Article 366: Section 2).

Next, there was the matter of fornication between relatives (with relatives including the wives of certain family members) for which Xie’s father-in-law, had he done as intended with force, would have faced death by beheading (Article 368: Section 2).

Our review of the relevant statutes suggests that raping one’s daughter-in-law was thought to be (at best) poor form in Qing dynasty China, just as it is in the United States today. The law reflects as much, giving the courts serious matters to consider. But other familial concerns—singularly irrelevant to modern legal theory but critical in Qing dynasty China—also demanded the attention of the jurists.

Competing against these laws against sexual assault were extremely specific statutes on the striking with intent to kill one’s parents or the parents of one’s husband, for which the penalty was death (Article 319: Section 1). For a woman to so much as curse her mother- or father-in-law or her husband’s paternal grandparents was also punishable by death. (Men cursing their parents or paternal grandparents faced the same punishment; however, men’s in-laws were not afforded equal protection from offense.) (Article 329) And the Code had no explicit self-defense theory upon which the courts or emperor could rely, further complicating the assessment of the case.

After several rounds of review, two years of detention for the suspect, and an action on the part of the emperor, Xie’s case was resolved. Although Xie’s original sentence was death, it was reduced to a fine paid in lieu of corporal punishment, with the emperor ordering that the case be treated as a binding precedent—an uncommon occurrence. Xie was not forgiven, nor was the slaughter of one’s relations valorized, but nor was she significantly punished.

Thus were a group of mandarins and the emperor able to craft a sentence that neither violated core Confucian principles nor placed potential future victims of similar assaults in an untenable position. Given that the average time to disposition of a non-capital felony case in the United States is 256 days (not counting appeals), a few years to address the complex legal concerns and theories in Xie’s case seems reasonable. And the events of this case occurred around 1830 (about 27 years after Marbury v. Madison for those who are interested) in a country in which long-distance transportation and communication and transmission of legal documents were difficult.

The mandarin scholar-leaders dynamically adapted traditions, punishments, and customs according to circumstances and the dictates of fairness, just as Confucius believed they should. One could reasonably argue that the Chinese system of justice proved at least as effective and nuanced in its reasoning as did the American system in the cases mentioned in Part I of this series. But the Chinese system worked on incremental, not transformative, principles. The emperor had other ways to exercise his authority if he wished to induce radical social change.

In such a system—one that favored gradual evolution of thought, in which general scholars served as investigators and judges, and in which legal professionals were forbidden—there was no role for an activist legal community. Some local reformers, such as Liu Heng, worked within the government, but their reach was limited. The attorney as knight—the American interventionistic model—would be no less out of place in the court of the emperor would than a Connecticut Yankee in that of King Arthur.

While this system had its strengths, the need for modernization of the Great Qing Code and legal customs became evident after China’s interaction with the British and American imperialists. Thus, modernization began with fits and starts. Several Chinese researchers traveled to continental Europe in the early 20th century to determine what made its legal systems effective and what parts were worthy of emulation. These scholars ascertained that all of these systems had a shared heritage of Roman law. Under their recommendation, the study of ancient Roman law was actively encouraged in China, and a new legal code based on such law was implemented, with the Great Qing Code being supplanted. (This supplantation was imperfectly executed throughout the Sinosphere, with the Code being referenced in a Hong Kong case—W v. Registrar of Marriages—as late as 2013.)

Later iterations of Chinese law incorporated (at various times) an American-style bill of rights and Soviet and German legal constructs. That these sources were all founded on radically different notions of human rights and responsibilities, the role of family, and the function of government would appear to make them singularly incompatible. Such has not proven to be the case. The Mainland legal system—much like modern music with a heavy emphasis on sampling—can be said to have borrowed from the many while remaining a creature apart.

And despite these apparent theoretical contradictions, the Chinese matrix for values development is still essentially intact. The system continues to assign a higher priority to collective than individual wellbeing—the many over the one—and favors a non-activist court system. And it, like the Napoleonic tradition, makes little use of precedence, although this appears to be slowly changing.

When left to its own devices, the Chinese legal system tends toward a gradualism that stands in sharp contrast to the destabilizing social engineering of its modern American counterpart. And its matrix of values development has proven stubbornly resistant to anglicization.

Hong Kong—its legal system already mentioned—provides interesting examples of what happens when common law courts established under British rule and the Great Qing Code meet, with the latter becoming a reference, much like case law, for the former. There remains in Hong Kong a lingering respect for families and family clans as institutions capable of some autonomy, including in regards to the resolution of inheritance and succession issues. This harkens back to ancient custom in China, in which the courts acted as much as mediators in family matters as strict imposers of order—a practice that may continue for generations more.

The professionalization of the Mainland Chinese courts is a recent development. The courts during the Republican/interregnum era (1911-1949) applied laws variably, depending upon local factors. Urban courts relied more heavily upon Western notions of law when addressing civil cases, and rural courts were predictably more conservative and inclined to rely on Qing Code. The subsequent actions of the pre-Cultural Revolution Communist China (1949 to 1965) courts fall within something of a lacuna of history. However, the available records suggest that they—the courts in Beijing most of all—served as testbeds for varied legal theories and practices promoted by the political system. In the Cultural Revolution, the subordination of the courts was pronounced, reflecting Mao Zedong’s view of legal procedure as a necessary evil. They performed erratically and with minimal autonomy from the Communist Party and its overarching goals during that era—namely suppression of counterrevolutionaries.

Normal court functions resumed not long after Mao’s death, which is not to say the courts were aligned with Western standards. A critical reassertion of the rule of law was the trial of the Gang of Four—the four most prominent and ruthless leaders of the Cultural Revolution—which began in 1980 and concluded in 1981. As imperfectly conducted as the trial was, it demonstrated a move away from revolutionary justice and towards a system of process—with indictments, judges, defense attorneys, and a hearing. Thus, the great non sequitur of Maoist rule came to an end and China resumed its slow advancement towards a modern, but distinctly Chinese, legal system.

From 1978 to 1995, one’s case might have been decided by a law school graduate, a military veteran, a court staff member, or a high school graduate recruited by the court system. In recent years, the role of judges has become more distinct, and judges are required to pass proficiency tests, with similar tests being offered to would-be attorneys.

This represents a significant shift in the Chinese legal system, demonstrating the rise of working legal professionals and an increased respect for the profession. Yet the fundamentally subordinate nature of the courts remains unchanged, as it likely forever will. At present, the Supreme People’s Court, the highest in the nation, reports directly to the National People’s Congress, which has the authority to add or remove judges as it sees fit. At worst, we could accuse the Chinese legal system of being a puppet of the political system. But such may be less accurate than it is a misunderstanding of the long-established role of courts in the Chinese tradition. Most charitably, we could describe it as embodying neither rule of law nor rule of man, but rule of common weal.

With our recently improved knowledge of the Chinese legal system and matrix of values development in relation to those of the United States, we can advance this section’s thesis. The mandarins and knights are behind us, but never far away. And Milgram—last mentioned in the first article in this series—trails them both: Regardless of law or matrix of values development, the average man is passive. He is neither knight, nor mandarin, nor inclined to question either.

Now, we ponder what effect, if any, this matrix has had and is likely to continue to have on China’s economic, cultural, and technological development.

Belief, Philosophy, and Development in Practice: China, the West, and History

When considering the above Chinese beliefs and values and how they and their matrix of development differ from those of the West, at least two questions may come to mind:

- Is there something inherently limiting in Chinese beliefs—in the abstractness of Daoism, the rule-following and conservativism of Ruism, the nonattached morality of Buddhism, or the interaction of the three—that caused China to fall behind the West, despite the former’s considerable history of applied science and technology?

- If the answer to the first question is in the affirmative, does the ongoing influence of these beliefs dictate that China will forever remain a follower of the West in more ambitious intellectual domains?

The first question is exactly the sort of negative inquiry (Why didn’t the dog bark?) that invites speculation from all and sundry, with no single opinion/answer being undeniably, irrefutably correct. But an examination of a few theories stands to be worthwhile, if for no other reason than that doing so provides some insight into how the (largely Western) theorists describe the developmental arc of China’s history and civilization.

We must distinguish between the metaphysics of a belief system—how that system defines and describes reality—and the values of a belief system, which dictate personal behavior, social interaction, concepts of justice, and (at least occasionally) affairs of state. The thesis presented in this section is that the metaphysics of Chinese beliefs likely did little, if anything, to slow China’s development, whereas the values of certain Chinese belief systems—Ruism in particular—might have had a deleterious effect. The distinction between these two—metaphysics and values—is critical, and it is one that we will consider more in the next section.

Scientist, historian, and sinologist Joseph Needham suggested that China’s philosophy of organic materialism—the view that nature is an integrated system that is unamenable to reductionism and experimental control—was a mixed blessing. It both allowed the Chinese some early technological advances that relied upon their capacity for holistic assessment of the universe and impaired the development of empirical investigation techniques. He also speculated that the Chinese view would eventually integrate with and complement the modern physical sciences, which are increasingly likely to present phenomena as emergent and complex.

Conversely, in Why the West Rules—For Now, historian Ian Morris developed a more geographical argument (covering a much longer timespan) for Western domination of the world. He posited that certain advantages in the natural environment allowed the Western peoples greater access to wealth and energy, which facilitated their economic and technological development. Thinking such as this would assign philosophy, no matter how great the thinker who developed it, the role of product more than producer of civilizational advantage. This position—similar to the one taken in this text—does not relegate philosophy to irrelevance, but sees theory as trailing practice and economic incentives. Understanding starts with authentic observation, which is inductive, organic, and universal to all intelligence (including that of the non-human variety). The better part of reasoning is post hoc and flawed.

Finally, Ken Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy suggests that the difference between Western and Chinese civilization was negligible until the 19th century. It was during this century that Europe’s easy access to coal and resources from the New World allowed it to pull ahead. As for the counterargument that access to the New World was the product of existing European technological superiority, we need but think back to the Ming dynasty and the great adventures of Zheng He. We can recall that China’s failure to reach the Americas was more the result of a political miscalculation than one of maritime ineptitude.

And these are just three of many theories attempting to explain the past and present differences in Eastern and Western economic development. There are others. Using them as a starting point, let us consider what we do know:

Assertions of present and near-past Western technological supremacy are correct. The West has dominated the world for several centuries. This will likely end soon—not long after the Chinese economy overtakes that of the United States—but a forecast of sunshine tomorrow does not negate the reality of today’s rain (or vice versa). China had no equivalent to the European Age of Enlightenment and the subsequent rise of positivism, the latter of which shifted Western thinking away from the abstract and unfalsifiable to the physical and empirical. The lack of these intellectual upheavals may have slowed the development of Chinese science, technology, and engineering. But may is not a synonym for must.

Relevant or not, the West’s philosophical shift was recent. The Enlightenment began in the 17th century, and Auguste Comte developed positivism in the 19th century. As for who—China or the West—was ahead before then depends upon whom one asks. What can be noted with certainty is that the Western world rose to unquestionable prominence, pulling far past China in science, technology, and material wealth, during the reign of the forever insecure and extremely conservative Qing dynasty. This dynasty was strongly incentivized by its outsider status to avoid radically altering the culture and traditions of a distinct people—the Han majority—lest it be accused of destroying a civilization that was not its own to harm.

As for Needham’s argument of theory before practice—meaning that the non-empirical theory of organic materialism prevented Chinese technology from advancing beyond a certain level—history offers a firm rebuttal. Before the latter half of the 19th century, Western natural philosophy was permeated with untested theories—of the humors, of luminiferous aether—which were so off the mark as to be meaningless. Yet innovation preceded understanding.

The first marine chronometer—a tool essential for calculating longitude was developed in 1730 by John Harrison, a carpenter who built his first wooden clock when he was 20 years old. Harrison had no formal scientific training and began his work decades before positivism came into being. His first design was too inaccurate for navigational purposes, but such did not deter him. And the 30 years Harrison spent refining his design (completing his award-winning iteration in 1761) were not dedicated to pondering abstract concepts, but in active experimentation—the same sort of experimentation used to perfect designs throughout human history and prehistory.

We should not neglect to note how quickly philosophies and views can be adapted to their times. Rates of innovation are elastic in that they are sensitive to market forces, hence the extremely rapid development of technology during wartime and the motivational power of prize money—the pursuit of which drove Harrison for decades. And culture is neither concrete nor water. It is closer to a non-Newtonian fluid—apply a little force and it responds as would a liquid, apply too much and it acts as a solid.

Chinese metaphysics cannot be faulted for the civilization that developed it falling behind the West. Rather, the emphasis on stability over growth (a product of both Manchu policy and Ruism) within China during a critical era of global development produced an environment in which there was no immediate pressure to advance said metaphysics.

Chinese metaphysics cannot be faulted for the civilization that developed it falling behind the West. Rather, the emphasis on stability over growth (a product of both Manchu policy and Ruism) within China during a critical era of global development produced an environment in which there was no immediate pressure to advance said metaphysics.

The Self-Strengthening Movement (1861-1895), an attempt at infrastructure and military modernization that concluded a few years before the Hundred Days of Reform began, succumbed to the abortive pressures of a sclerotic Confucian mandarinate. But this is not an unequivocal testament to the failure of a given philosophy (or philosophies), for such resistance to change is likely as much the result of structural and economic factors of a more mundane and temporal origin. Let us not forget that Christianity demands obedience to authority and that one offers those who smiteth thee on the one cheek the other also. Yet the historically Christian nations have proven to be some of the most intellectually productive, rebellious, and militarily competent.

Now there is the matter of us—the Americans—resting on our laurels. To determine why we do this, we must engage in an investigation into the effects of structurally induced complacency. To answer how this will affect future rates of innovation in the United States, we will need to pull from our knowledge of history, economics, sociology, and psychology.

In any culture, scientific thinking and a spirit of honest inquiry are the exceptions more often than the rule. We are a hierarchical species, finely attuned to indications of power and status. We may prefer the confidently wrong over the hesitantly right, and the profoundly wrong can be some of the most confident of all. Science offers no certainty. And we are certainty seeking animals. Every theory remains (at least in theory) a theory that any person acting as a scientist, regardless of credentials or the lack thereof, could potentially challenge and disprove. To be true to their profession, scientists must have loyalty to process and rigor, not to people, and not to personal comfort of either the social or material sort. At best, this is a tall order. At worst, it is a mile-high one, suited to none but the most tenacious amongst us—those with a refractory (and occasionally masochistic) passion for the truth that is strengthened by the withering heat of nearing it.

Amongst the many warnings given in President Eisenhower’s address, one of the more relevant is that “in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.” Consider this and the effects of the near monopolization of research funding by the government—of undeniable importance during Eisenhower’s time, and far more so today—and think back to the contrasting matrices of values development.

Highly literate in a canonical arcana few outside their group have the method or means to effectively challenge, with a language (or dialect) of their own, and governed by a leviathan paymaster—such describes the Qing mandarinate to a T. It describes our emergent technocratic overlords no less well. The American scientific/academic funding complex is nominally positivistic, not Confucian, but its structural dynamics stand to transmogrify it into something functionally indistinguishable from a consensus-oriented matrix of values development. In any stable, centralized society, a certain respect for bureaucratic order and conventions overwhelms and erodes the spirit of risk-taking and free thought. At its worst, this can prove singularly corrosive to innovation.

The larger American matrix of values development remains feudal, but the scientific/academic funding complex is a system somewhat unto itself. Yet it is not strictly mandarin. Here are the key differences between it and the Chinese matrix:

- The traditional Chinese matrix was populated with generalists, whereas the scientific/academic funding complex is populated with specialists.

- The traditional Chinese matrix interacted with the public regularly, at least at the level of county magistrates, whereas the members of the scientific/academic funding complex are shielded from interaction with the unwashed peasantry.

- The traditional Chinese matrix placed great emphasis on social cohesion within the family and larger community. The scientific/academic funding complex addresses family and ordinary social relations obliquely. Essentially technocratic, this matrix treats community relationships (outside the academy/matrix) as either experimental curiosities or archaic insofar that they interfere with the ability of the siloed matrix to propagate its foundational worldview.

Describing the American scientific/social science/technological class as mandarins would be inaccurate. A better term for American experts might well be siloed mandarins due to the disconnect they have from both those in other fields and society at large. And the system of which they are a part could be fairly described as the siloed mandarinate matrix of values development (hereafter shortened to siloed matrix).

The siloed matrix is fundamentally similar to the Chinese consensus matrix in that both value harmony and agreement over combativeness and competition. The siloed matrix differs from this in that harmony is valued within the field of expertise, but not necessarily in relation to anything or anyone else.

The most relevant effect of this construct is that it can slow the advancement of understanding and innovation, even in fields one might assume are pure and outside the realm of politics. For example, theoretical physicist Sabine Hossenfelder observes that mathematical elegance has come to be taken as an essential element of working theories in her field. She also argues that adherence to this prerequisite, which is difficult to violate within the consensus-driven siloed matrix of values development, has interfered with the process of discovery by positing ideas that are not even wrong. In a field in which access and credibility are controlled by a select number of institutions and officials—one that is gatekept—consensus is enforced in many ways. Financial restrictions (denial of access to grants), limitations on employment opportunities (denial of tenure), and subtle social pressures have the potential to be every bit as effective tools as is the violence of governments. Imposed consensus is not identical to groupthink. Groupthink typically lacks an economic element.

None of this is to say that Daoism, Ruism, or Buddhism have not influenced the development of China, just as Christianity and the earlier pagan traditions absorbed and supplanted by it surely did as well. But within this specific domain—that relevant to the growth of empirical knowledge—we cannot establish with any certitude that the traditional religions and philosophies of China in their metaphysical aspects impaired her development.

What we can establish is that the matrix of values development in which a body of knowledge exists can shape its direction and rate of advancement. This is not a matter of metaphysics. It is a matter of socioeconomic, cultural, and political factors of far greater complexity. In the United States, one of the few fields that is proving highly adept at advancing humanity’s understanding of its fundamental nature is marketing. Driven by and driving technological innovation—in everything from artificial intelligence and data science to the fundamentals of psychology—marketing is big, complicated, and effective. But its paymasters—companies—demand results, not ego-stroking and consensus. Both the strength and importance of marketing and the power of market incentives to produce good (actionable) research will be considered in the sections that follow.

Much of what we have addressed thus far occurred in the past, where innovation occurred. The present and future are no less relevant.

Metaphysical Drag and Values Drag: Effects on Industriousness and Innovation

After considering the past, we turn to questions of the present: If the answer to the first question is in the affirmative—meaning that the tenants or practices of China’s major beliefs somehow slowed the nation’s technological and scientific progress—is this relevant now? Does the ongoing influence of these beliefs dictate that China will forever remain a follower of the West in more ambitious intellectual domains?

Perhaps this line of inquiry seems unnecessary. We have already made some effort to establish that the first question should not be answered in the affirmative, at least in regards to the metaphysics of Chinese beliefs. Yet not all may agree with the line of reasoning used in the previous arguments. Thus, we will proceed as though our reasoning has been proven inadequate and consider the relevance of metaphysical drag. Additionally, we will take into another matter—that of values drag—and argue that neither it nor its metaphysical cousin will prove of no more consequence to China in the next century than they will to the United States.

The first possibility is that despite all evidence to contrary, adherence to Chinese metaphysics has somehow slowed the development of a robust, technologically sophisticated society and that this metaphysical drag impairs innovation to this day and will continue to slow innovation in the future. The second possibility is that the Chinese metaphysical beliefs are compatible with the accumulation of knowledge but that Chinese values have produced such a hidebound and deferential culture that the creative capacity of China’s people has been stunted.

First, metaphysical drag.

The capacity of a people to modernize their beliefs—as the Westerners did during the Age of Enlightenment—has already been examined. What has been given less attention is the ability of people to hold profoundly contradictory ones. Needham’s theory—that organic materialism interfered with the development of science in China—is appealing at first look to those singularly oblivious to human nature. It assumes that humans require logical consistency to thrive in their intellectual pursuits. Such is profoundly wrong. We are rationalizing animals, not rational ones. And the human capacity to adjust theories automatically and instinctively while maintaining the illusion of consistency is astounding. In the previous section, we noted that a people can have profoundly inaccurate beliefs in one domain but advance quite effectively in another. Thus, the peoples of Europe could develop increasingly effective navigational technologies while continuing to believe in the aforementioned luminiferous aether. This is a matter of an uneven rate of knowledge development, which is different from that of outright contradiction—the topic we consider below.

Christianity, a religion that demands (but does not always receive) belief in miracles from its adherents, has been the faith of several prominent scientists. Freeman Dyson (of the Dyson sphere, not the vacuum cleaner) furthered the theory of quantum electrodynamics, collaborated with Edward Teller to design the TRIGA nuclear reactor, and contributed to Project Orion—a plan to use atomic bombs to propel spaceships. He managed all of this without a Ph.D.—something in which he took pride. He also considered himself a “practicing Christian up to a point but not a believing Christian,” who took the resurrection of Jesus as fiction. And Christians and Buddhists alike have found no great difficulty in justifying war, despite the emphasis their faiths place on non-violence.

Even were the metaphysics of Chinese beliefs so profoundly incompatible with rational thought that anyone who studied with more than semi-serious intent for a long weekend was left in a state of enduring befuddlement, the Chinese could still progress. They, like the rest of humanity, could believe one model of the universe to be true while living in accordance with a radically different one. The human capacity for irrationality is probably one of the species’ greatest strengths. It is better that we advance haltingly, haphazardly, and with messes of contradictions than that we are so chained to logic that we never advance at all.

Next, we turn to values drag.

Ruism places tremendous emphasis on respect for one’s elders and for awareness of appropriate conduct for one’s social station—a matter we have seen to be critical in its tradition of jurisprudence. And its prioritization of stability over growth—on good governance and national development more than colonial expansion or omnipredatorial consumption—may have lessened the need for technological development. Finally, the ability of China’s civil service system to competence capture—meaning recruit the best and brightest into government and keep them from growing restive—has been mentioned as well. But there is another matter to take into account.

Daoism and Buddhism both promote a resignation to the transient, flowing nature of life so much so that attempting to change one’s circumstances may come to be seen as futile. Ruism emphasizes fate no less. This ties to fatalism—a doctrine and worldview more widely believed by Asians than Westerners. There is something to be said for the argument that a fatalistic view carried to its logical conclusion would lead to passivity and acceptance of the will of one’s superiors and the whims of nature. Fatalism could interfere with scientific investigations if only because the fatalistic would see no point—Nothing can be done to change our fate, so why worry about the cause of anything?

But one should not assume that the fatalistic are purely so. One is but occasionally so resigned to fate that he considers effort without any value at all. Few men will open their mouths, look upwards, and wait for either manna or guano to fall from on high, confident that they will eat comfortably or die uncomfortably (from salmonella), per the dictates of heaven. There is nuance to the non-fatalistic fatalism of China that may not be obvious from a culturally naïve reading of core Buddhist and Daoist texts.

An example—

Chinese students have been found to believe that academic success is the result of hard work—something one can choose (or not choose) to do—more than do Americans, who often see academic success as a product of intelligence. This would suggest that the Chinese believe more strongly in their ability to change their fate through effort than do Americans, but this conclusion is complicated by the relative frequency of the growth mindset. Compared to the Chinese, American students have this in greater abundance—meaning they believe they can change, grow, or develop their intelligence and personalities—their core being—by way of training, a fascinating notion that has been almost entirely debunked.

Stated simplistically, Americans accept as true that one can improve what he is on the most fundamental level and then achieve greater levels of success with what he has become. The Chinese believe one cannot exceed certain inborn restrictions—a more fatalistic view—but that one can improve what he does by making the best of what he has always been. And this simplification is imperfect (as simplifications are wont to be). One must keep in mind the Buddhist emphasis on achieving enlightenment—not exactly a mechanism of self-improvement as it emphasizes non-self but hardly indicative of resignation to stagnation.

In practice, much of what has been described amounts to a distinction without a (meaningful) difference. Hard work to improve one’s innate self and hard work to improve one’s performance (while leaving the self unperfected) can be functionally indistinguishable. Practice is practice. Hard work is hard work. Improvement is improvement, regardless of the theory behind it.

Fatalism should be a values drag—causing students and families to accept their fate. Yet the evidence bears out nothing of the sort. The Chinese have considerable confidence in the power of struggle to improve one’s condition. There are few other explanations for the herculean efforts they make better the individual, family, and national lot.

Perhaps the Chinese are less fatalistic than the research suggests.

Research comparing Chinese and Western perceptions of fate is primarily designed in the West and administered to the Chinese living in the United States or Europe. Thus, there is the distinct possibility that what the researchers are incorrectly categorizing as fatalism are actually beliefs more influenced by wu wei. To change one’s nature—as one with a growth mindset is wont to do—is to swim up a waterfall. To work within the limits of one’s abilities (and to make the best of them) might not qualify as effortless action, but it would seem less effortful than efforts to forge a new self ex nihilo.

Now we turn to the final source of values drag considered in this essay—complacency.

Complacency is not a philosophy, nor is it metaphysics. But it is a value of sorts—the valuing of a tolerable present over the chance of a grander future—and it may prove every bit as restrictive as the more inflexible moral conventions. The Qing and Ming dynasties were complacent, regarding China as the center of the world and outsiders as barbarians unworthy of emulation. China paid dearly for this. By abandoning the fruits of Zheng He’s exploits and his legacy of adventuresomeness, the Chinese authorities put themselves and their nation at a significant disadvantage relative to the Western colonial powers. The British, for example, skimmed $45 trillion off the Indian economy from 1765 to 1938 by way of taxation without representation, and the rest of the British Empire likely profited the mother country similarly. It is highly unlikely that the Chinese leadership is ignorant of this lost opportunity or would wish to make another mistake of this magnitude.

The age of colonialism has come and gone, and China, even in the days of Zheng He, showed no great enthusiasm for conquest in the proper sense of the word, preferring trade and tribute. As much the result of Chinese pragmatism as it is of the country’s decidedly non-proselytizing religions—with neither Daoism nor Ruism rewarding one for saving souls—the Chinese objective in global affairs is one of profitable, undiscriminating commerce. The Chinese may not be entirely averse to interference in the internal affairs of other nations, but they have proven no more interested in this than is necessary to promote the flow of goods, services, minerals, and money. This pragmatic strategy is exemplified and implemented in the form of the Belt and Road Initiative—a modern reimagining of the silk road.

The goal of the Initiative is partially one of soft power, with the establishment of Confucius Institutes and language-training centers around the globe, but it is primarily commercial. And unlike the ever-profligate American Empire of Debt, the Initiative may improve taxpayers’ quality of life, rather than serving as a form of reverse socialism—extracting money from the citizenry and awarding it to massively wealthy corporate interests.

The Chinese elite of today are not complacent. They are no more self-satisfied with their state of knowledge and the sophistication of industry in their country than they are with their role in global trade. Rather, their national education plan consistently emphasizes the importance of science and technology and describes several programs to attract talented foreign researchers. These programs, certainly those to lure the best and brightest from around the world, are substantial and properly funded. The borders of China may now and long into the future prove impenetrable to the average Harbin-swilling, backpack-schlepping English teacher. However, the government is willing to leave the gates ajar wide enough to allow those with real competence into the country and to permit profit to enter not much more impeded. And if research and researcher are of real utility, the powers that be will have no problem overlooking parking-ticket caliber transgressions that cause America’s fainting-couch feminists and their university stooges to cry havoc. The Chinese are capable of engaging in economically and scientifically gainful international collaborations with the outside world (despite their growing insularity) even when American institutions are less comfortable with the matter.

Yes, China’s cycles of openness and closure must have done something to slow the propagation of foreign knowledge in China and Chinese knowledge to the outside world, just as they restricted her commercial activity and growth. But without the early consolidation of China into a single nation, this would have been impossible. There is no evidence to suggest that European powers would not have done the same, but that they could not. The lack of a centralized power in Europe able to unilaterally reject an idea or forbid an activity was a strength presenting as a weakness. It is what allowed explorers and innovators to shop their ideas to one royal household after the next, such as Christopher Columbus did several times before the Spanish finally agreed to sponsor him. Yes, the errors of the close-minded mandarinate and the Qing dynasty were real, extensive, and (at least to the people of China) tragic. And yes, the Chinese matrix of values development promoted incrementalism in legal innovation, and (possibly) in technology. But we should not assume that the resultant mistakes will be repeated.

By the Chinese.

The United States is another matter, and this leads to another possibility that would cause us to answer the question put forth in this section in the negative. The Chinese rate of innovation may not equal that of the United States at its best, but the United State may fall so far from her day of glory that the Chinese need not prove overwhelmingly inventive to best her. The current Chinese research funding scheme is quite similar to that of the United States—large amounts of money being distributed by a central authority. There is no compelling reason to believe that this top-down approach to science will not work as well (or as poorly) in one country as it does in another.

And there is some reason to believe that China may manage her centralized system of scientific funding better than will the United States. Politics as science is not science at all. At best, it is harmless idiocy. At worst, it can starve entire nations. Certain countries have learned this the hard way—China included—with that possibly being the one way this horrifying lesson can be learned.

Science can (and often does) serve political ends—from the development of better weapons to the creation of new technologies to control human behavior. Tyrants and tyrannies may well advance the fields of science and engineering. (The Nazis did.) But if research is to lead to the systematic discovery of knowledge—is to be of consequence—its backers must be willing to accept results that do not match their expectations. Scientists can be forced (to work more, to work harder, to publish manipulated or fabricated results that confirm this or that). Science—reality itself—is amenable to no one and nothing. Supporters of research forget this at their peril. A scientist (rather than a careerist with a science degree) who finds himself in the position of being beholden to anyone more interested in predetermined conclusions than in honest discovery would do well to find a different source of funding.

In China, this is difficult. In America, it is not much less so. But the Chinese have the advantage of having learned the wages of seeking consistency with ideology over consistency with nature. This was the result of an education that was expensive for humans and sparrows alike.

There is the distinct possibility that our science and research will suffer—has already suffered—under centralized control. The United States avoided many of the hardships of the 20th century. The closest we experienced to an agricultural failure was the Dust Bowl, which resulted in hundreds of thousands of plainsmen abandoning their farms, but relatively few deaths. And compared to China, Japan, or the Soviet Union, the United States was spared much of the agony of the Second World War. We did not suffer any great political upheavals equivalent to the Cultural Revolution, the Cambodian Genocide, or the collapse of the Soviet Union. Some of this mercy was granted by virtue of our having two of the best possible defenses against European and Japanese belligerence—the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans; however, much of it was the result of inefficiency. Our government has been too politically divided and too much a mess of overlapping jurisdictions and sometimes contradictory laws to solve our problems. Our Holy Roman Empire of judicial and legislative principalities has its advantages.

A weakness can be a strength, just as strengths are often weaknesses: The government too inept to find solutions is the one too disorganized to inflict them, in all their centrally planned horror, upon the people. And until a few decades ago, private, decentralized research played a far greater role in American advancement than the champions of government intervention might care to admit, establishing that science is not the exclusive bailiwick of government.

We should be wary of surrendering authority over knowledge to those within the siloed mandarinate matrix of values development. If this handover is completed—if science is made to conform to the correct thinking of fanatical sheep—it may not take much for China to at least keep pace with America’s scientific advances. We risk falling behind not so much from ignorance of our history, but ignorance of history in general. The mistake of allowing a knowledge elite to delegitimize amateurs and independents—the private researcher, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, to which President Eisenhower referred in his farewell address—would be grievous beyond measure. That of permitting the playfulness of the genuinely curious to be replaced by the ineptitude of the cadre, the upright misery of the ideological purist, or the sadism of the fascist would be no less so. Either stand to gift China a significant advantage in every meaningful realm of development.

None of this is to argue that the United States government should not fund science, basic research most of all (although award-winning basic research can and has been done by private industry). Rather, there should be no attempt to monopolize innovation, funding of innovation, or fair credit for ideas, regardless of the credentials (or lack of credentials) of those who have them. Nor should we allow the technocratic apparatus to become too adept at vacuuming up our best and brightest, as did the mandarinate of China: Every society needs a few discontented geniuses and outsiders. Little can change for the better without them.

Equally important is that science be supported to fuel discovery, not to produce predetermined experimental outcomes, and not with regard for the rightness, wrongness, or outright absurdity of the personal and political stance of the scientist. The apparent moral or ideological goodness (or acceptability) of the scientist is little indication of his professional aptitude, aptitude for creative discovery, or trustworthiness. Likewise, no one, regardless of prestige, prodigiousness, or frequency of publication, can be above skeptical review and attack. If we—the United States—cannot keep this lesson in mind, we will suffer mightily for it, as the Chinese and the Soviets did for long and awful decades.

Now that we have considered Chinese history and culture at length, both independently and in relation to other nations, we turn our attention to problems presently faced by China, both shared and distinct from those of the United States.

Problems, Problems Everywhere: China, the United States, and Continuity Concerns

Both China and the United States face challenges to their civilizational continuity—major existential threats. Some are unique to one nation, some are common to both but distinct from those shared by the rest of the world, and some are problems so integral to modernity that finding a nation without them would be nearly impossible. First, we consider the problems faced by both nations.

Stages of Grief, Stages of Decay: Social Relationships, Stability, and Economics in China and the United States

We will take it as established fact that Americans are isolated. There is research to support this, including that in the aforementioned Bowling Alone. America Against America makes similar observations.

Yet China is not immune to the disconnecting effects of modernity. The Chinese people have the benefit of learning from the mistakes of the United States. If they will is another matter.

The two most obvious issues faced in this domain are:

- The decline of family

- The (related) increase in the number of disaffected citizenry/young men

Despite the import of Confucian thinking, the Chinese family has been on the decline for decades. Even as far back as when Wang Huning was conducting his research for America Against America, divorce rates in China were on the rise. This was at least in part due to a 1981 law that made getting a divorce easier than it was years prior.

And the divorce process was simplified again in 2001 when work unit leaders were removed from the divorce approval process. (The work unit is a distinctly Communist entity that functioned within the planned economy of China as a critical organizational tool. Its importance has diminished in recent decades.)

Despite some efforts on the part of the government to stem the tide of divorce, including the introduction of a waiting period before a divorce can be finalized, Chinese divorce rates continue to increase, and they likely will for years. And just as is the case in the United States, the majority of divorces are filed by women.

Perceptions of divorce and divorced women are changing, with China’s first divorce reality television show, Goodbye Lover, streaming on Mango TV, which is under the control of the government-owned Hunan Broadcasting Company, in 2021. That a state-controlled streaming service chose to address the topic of divorce directly is not a trivial matter.

Those unfamiliar with Chinese television may not fully understand its role in the country and national psyche. To describe Chinese television as being uniquely propagandistic is inaccurate. It is propagandistic, but American television is as well, if not always for warmongers, at least for marketers.

In China and America, the medium of television is fundamentally the same in its propagandistic power, but the message differs. Granted, the medium may well be a message itself. But such does not prevent the message within the message from being carefully controlled and engineered. In China, the messages promoted are often patriotic, with romantic ones not far behind. The rationale for government-sponsored content promoting patriotism is self-evident. The utility of promoting romance is less so. And the United States produces its fair share of romantic films as well, so what is the difference?

Unlike American television shows and films promoting the abandonment of marriage and family to find the ever-elusive oneself, Chinese television programs consistently frame happiness within the context of a stable family. Family problems are not ignored, but they are generally presented as manageable and worth solving. There are deviations from this—The Piano in a Factory took an honest and critical view of the breakdown of relationships, but it was the exception more than the rule.

For a government-backed program to directly tackle the matter of divorce, presenting it as sometimes inevitable, constitutes a radical shift. It suggests that the Chinese government is well-aware that it simply cannot turn back the clock. It is now trying to make the best of what it likely sees as a bad situation. Marriage is dying in China, just as it is throughout the developed world. For those who subscribe to Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief, we can suggest that the Chinese government is now at stage three—bargaining—with the idea being that the demise of marriage can be, if not avoided indefinitely, delayed.

Both the government and the citizens of the United States have an advantage here. We are further along the grieving process, with some in a state of depression but a fair number having accepted reality for what it is (the fifth stage). And then there is the recently added sixth stage of grief—finding meaning—with more Americans turning away from long-term relationships and discovering and creating purpose outside the framework of traditional relationships.

There is no easy way to cross the bridge (or the river, if you will). The death of marriage will lead to complex social and economic issues, and mild traditionalism (the sort found in the developed world) will do nothing to stop it. Both Japan and South Korea have seen declining marriage rates, and this is despite them having cultures that are both traditional and closely related to that of China. And childbearing rates have dropped in Japan and South Korea alike. The counterargument that these cultures are too traditional and that more socially progressive policy and culture, with better support for families, can reverse this trend, does not hold water. In Norway—probably as socially progressive a country as one could find—birth rates have been dropping for years, and one out of five men in Norway will likely never have children. Sweden, as socially progressive a country as one could hope to find, has seen declining birth rates for 70 years. And spending more time around one’s partner exacerbated declining birthrates and family disintegration: The COVID lockdowns of 2020 correlated with a baby bust (definitely in the United States and presumably elsewhere) and an increase in the number of divorces filed.

Countries with high birth rates are consistently poor, largely African, and score low on measures of gender equality. Stated another way: Social and economic progress appear to be inherently incompatible with family stability and growth. No one, regardless of political leanings or nationality, has found a way around this.