Jewish author Alice Sepold made a vast fortune for herself by falsely accusing a black man of rape. Anthony Broadwater, a former U.S. Marine, spent 16 years in prison and had to register as a sex offender. Only this week, 40 years after she first falsely accused him, Broadwater finally cleared his name and was exonerated by the New York Supreme Court. Despite lying and repeatedly contradicting herself, no one is willing to publicly state the obvious, so I will. Alice Sepold is a liar and she should have kept her kinky rape fantasy to herself.

So far, Sepold has not apologized or even acknowledged the innocence of the man she ruined for money. The numerous holes in her story, the innocence of the suspect, and Sepold’s total lack of remorse afterward, are more than enough. The public should discard her entire narrative as false. How many times are we supposed to believe the girl who cried wolf? Everything that Sepold said about anything should be considered a lie unless proven to be true beyond a reasonable doubt. If Sepold said the sky is blue, I would still look outside, and then schedule an eye exam.

For a detailed explanation of how Sepold ruined Broadwater’s life, check out this article at the Daily Mail. Here’s a succinct summary:

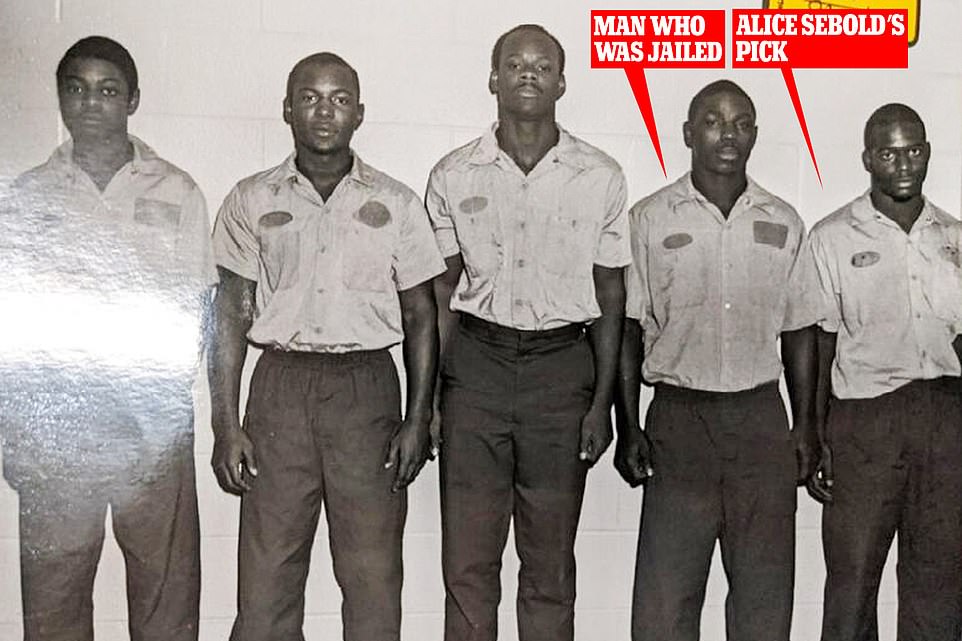

In 1981, Alice Sepold was an 18-year-old college student at Syracuse University. She went to the police and claimed to have been raped by a black man. The description she gave to police investigators and a sketch artist was too vague for them to realistically search for a suspect. Five months later, she saw Anthony Broadwater on the street and claimed to police that he was the man who raped her. However, she failed to identify him in a lineup.

Not one to let facts get in the way of her victim narrative, Sepold received coaching from the prosecutor, Gail Uebelhoer, and claimed under oath that Broadwater was the man who raped her. Sepold even insisted that Broadwater had taunted her the day she saw him on the street. In reality, Broadwater was talking to a policeman he was friends with (and the policeman confirmed this). Despite the inconsistencies in Sepold’s story, Uebelher moved forward with the prosecution and bolstered it with hair samples on Sepold’s clothing. Since then, this brand of forensics has been branded as pseudoscience, but that doesn’t help people who were already convicted with it, like Broadwater.

Broadwater went to prison. He was released, albeit as a registered sex offender, in 1999, but Sepold wasn’t finished destroying him for her own personal gain. That same year she published her first book, Lucky, a lurid and extremely graphic fairy tale about how he supposedly raped her. A rape fantasy isn’t quite enough content for a novel, or even a novella, so Sepold padded it with her fantastical (and often demonstrably false) descriptions of what happened during the trial. She even claimed that Broadwater put a “hit” on her roommate, who was then also raped. Sepold didn’t have any evidence, or even a plausible explanation for how a penniless man in jail can arrange hit rapes on people, but that didn’t stop her from writing all this gibberish anyway. I sympathize with the poor girl who was attacked in her apartment, however, there is one fact I take comfort in. I was unable to find any description of the apartment break-in except the one from Lucky. Sepold is such a compulsive liar that it is entirely possible that the second rape also only happened in her own head.

Sepold continued writing books. Her next one, The Lovely Bones, was even made into a movie. Her lies didn’t come under serious scrutiny until Netflix started an adaptation of Lucky in 2019. Karen Moncrieff came onboard as the director. Moncrieff is no stranger to controversy. She previously directed 13 Reasons Why, a series that many critics condemned for glorifying teenage suicide. Moncrieff immediately set about making strange changes to Lucky’s story. The biggest change was Moncrieff’s insistence that Broadwater be portrayed by a white man. Moncrieff’s strange behavior and oddities in Sepold’s original book caused one of the scriptwriters, Timothy Mucciante, to become suspicious. Moncrieff responded by firing him. Mucciante hired a private investigator to piece together what actually happened, and the rest is history.

I read Sepold’s book The Lovely Bones when I was in Afghanistan in 2011. It’s not a genre I would typically read, but I was bored and there was limited reading material. I borrowed the book from a very nice girl I worked with; she liked it, but was shocked by the first chapter. I don’t blame her. The Lovely Bones starts with the graphic rape of a child. It is actually a well-written book. But “well-written” and “good” are not the same thing, are they? The problem with The Lovely Bones is that it made absolutely no lasting impression on me except for sheer shock value. It is hard to forget the detailed description of a very young girl being raped and chopped to pieces, but that alone doesn’t make Sepold’s story a worthwhile contribution to literature.

There’s a deeper problem with Sepold’s work. There’s no substance to it. The Lovely Bones is like a joke with no punchline, or a nonalcoholic beer. The journey was interesting, but was the point? After the rape, Sepold actually has very little say. She has to string the reader along with more sex scenes.

You know how Hollywood R-rated action flicks like Beverly Hills Cop, Die Hard, Lethal Weapon and Under Siege have the obligatory scene when a female character goes topless for about two or three seconds? It’s art! Anyway, maybe this trope helps keep the viewer engaged. If you aren’t paying attention you might miss it. But there is apparently a rule written somewhere that you only see the boobs once, because those movies have something else to say. If Sepold made an action movie, she would have to include that scene multiple times because she actually doesn’t have anything else to say.

Thankfully the other sex scenes aren’t as bad as the first one, but often still questionable. The second most graphic sex scene in The Lovely Bones is when the little dead girl’s ghost comes back to earth and has sex with an adult man. What? It’s nice that she’s at the very least in an adult body, but describing a prepubescent girl in the shower with a grown-up and pulling on his pubic hairs is still weird. Especially because Sepold went to great lengths to establish that the girl isn’t aging in heaven. There’s no reason a person can’t grow up in heaven, that was entirely Sepold’s choice to make people stay the same. Oy, vey! Why was that necessary, Alice?

The Lovely Bones is an erotic story. To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with erotic stories and they can be quite entertaining if done right. What I’m saying is that Sepold is peddling porn while pretending to make some deep intellectual point about trauma, when she’s actually making no point at all. Her book shares a common problem with Cuties, 13 Reasons Why, and some of our film industry’s other more kosher productions. It’s like making a movie against puppy murder by murdering puppies on camera. Sepold’s opening chapter is hardcore porn for pedophiles. Is that okay as long as there’s a disclaimer that pedophilia is bad?

Sepold’s books are all stupid and all pointless, and actually that’s revealing about Sepold’s “rape.” She’s a talentless hack and knows that she’s a talentless hack. But she loves attention. Look at her Wikipedia page. She’s the most boring person on the planet. Her pretend rape encounter with Broadwater is literally the only interesting thing that’s happened in her life. Or didn’t happen, apparently. It’s sad and I would almost sympathize with her if she didn’t start a lynch mob against somebody. As a college freshman, Alice Sepold had money, privilege, and was conventionally attractive. But that wasn’t enough for her. She wanted instant fame without having to work for it. So she invented an imaginary crime against herself. Apparently, even that wasn’t enough either, so five months later she went out and found an appropriate Untermensch she could turn into her abuser.

Ian Kummer

Support my work by making a contribution through Boosty

All text in Reading Junkie posts are free to share or republish without permission, and I highly encourage my fellow bloggers to do so. Please be courteous and link back to the original.

I now have a new YouTube channel that I will use to upload videos from my travels around Russia. Expect new content there soon. Please give me a follow here.

Also feel free to connect with me on Quora (I sometimes share unique articles there).