Probably it is time I write something about the USSR.

I am 40 (born in April, 1982) and I am a survivor of…not communism, but of the collapse of the USSR. I also consider myself a Soviet person, because the first ten years are crucial to forming a personality and because I was a Young Octobrist, of course. Some older people, especially in Russia, will argue that the 1980s are not [classical] Soviet Union, but to be honest, it doesn’t stand to reason. Every decade between 1922 and 1991 was unique, so which is the reference one?

Anyway, I’m going to try to explain how I feel about the Soviet Union. Whenever there is a conversation about it, I criticise it among Russians, and praise it among foreigners. Russians have the right to judge it, foreigners – not so much, if you ask me. And here is why I think so.

The USSR was anything but an Evil Empire or “prison of nations”. Basically, it was a normal country for the most part of its existence. What I mean by a normal country is a place where there is a mean average level/proportion of human happiness and unhappiness. Judging by countries I visited, in every country there are happy and unhappy people, and, excluding war zones or disaster areas, the proportion seems to be about the same everywhere. By the way, I have always considered Cuba a normal country too (been there in 2007).

Back to the USSR though.

The Soviet system had some distinctive advantages: free education, free healthcare, [almost] zero inflation, zero unemployment, zero homelessness, free homes for people, peace (no hot conflicts), low crime rate, drugs were almost nonexistent, no mortgages, student debt, loans that pile up. All the benefits I mentioned were available and accessible for everyone, it is true.

The USSR was first to give equal rights to women both on paper and in real life. It happened right after the revolution. I could never think that as a girl I have limited choice of career options in life or that I am second-rate for any reason. When I grew up, I was surprised to learn about what happened during the Boston Marathon in 1967 in the States!

On the other hand, the USSR developed a range of flaws: cronyism often based on family or Party relationships, red-tape (still a problem in Russia, if you ask me), equal pay for unequal contribution based on standard rates, not on actual work and its quality (“уравниловка”), etc.

From mid 1970-s onwards people were irritated by an insufficient supply of consumer goods (fancy clothes people would see in foreign magazines, consumer electronics, etc). Of course, it gave rise to more corruption from those who could get stuff. The cause of this insufficiency is debatable, but when the whole Western world wages a cold war against your country, even minor mistakes in the economy and/or home policy can lead to a serious crisis.

As for democracy, I don’t think there was more or less of it in the USSR compared to the West. The West has always been better at appearances. They lie.

I will also briefly mention Stalin and the notorious GULAG issue.

First and foremost, camps were not invented in Russia. Poland had those back in 1920s, for example. Why GULAG got that much limelight then? Second, far from being an angel, Stalin was a man of his time, his counterparts were Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Hirohito, Churchill (a racist and warmonger who declared the Cold War on us) and some lesser devils from all around Europe. He was nobody’s fool and knew what was to come. His mission was to save the country and he was up to this job.

The GULAG part of Stalin’s rule did happen. The scale is blown out of proportion though. And the more I live the more I understand that you cannot ensure a fair trial to a Navalny-like scum while enemies are moving towards Moscow. There were innocent victims. Unfortunately. But was there a choice? I’m no judge. The same is true for industrialization. It was crucial to carry it out. Was there a way to do it better? Well, Putin seems to be trying to do Stalin’s job without Stalin’s mistakes. Let’s see what happens.

I will now say few words about propaganda and censorship.

Propaganda had its highs and lows in the USSR. Of course, during the war and right after it, it was omnipresent, later it got milder. Russians/Soviets also do have the sense of irony, as well as common sense, believe me or not. I now revisit Soviet movies with Ian, and I’m more and more convinced that totalitarian censorship is largely an instance of “fake news”. Movies often touched upon social matters and were quite critical of the reality, love and relationships were shown explicitly enough for people to understand that children are not brought to your house by storks. But there was a lot of taste, sense of measure, moderation and proportion. Of course, I’m speaking of the best movies, but there were dozens and dozens of those, and many don’t get old.

In the 1990s some directors started complaining about what was censored from their movies. And you know, in most cases I agree with censors. They simply did good editing. Taste, proportion, measure. And when unleashed, so to speak, many of those directors started generating total junk that no one wants to see more than once, if at all. So who was right? By the way, Soviet movies glorified women in all walks of life: mothers, researchers, teachers, actresses, managers, civil servants, soldiers, doctors, etc. When I saw the Pretty Woman, I felt it was a step back, actually. It glorified prostitution, comedy or not.

As for the church, my mother born in 1955 was baptised. Nuff said.

Now about the Cold War and who won/lost it.

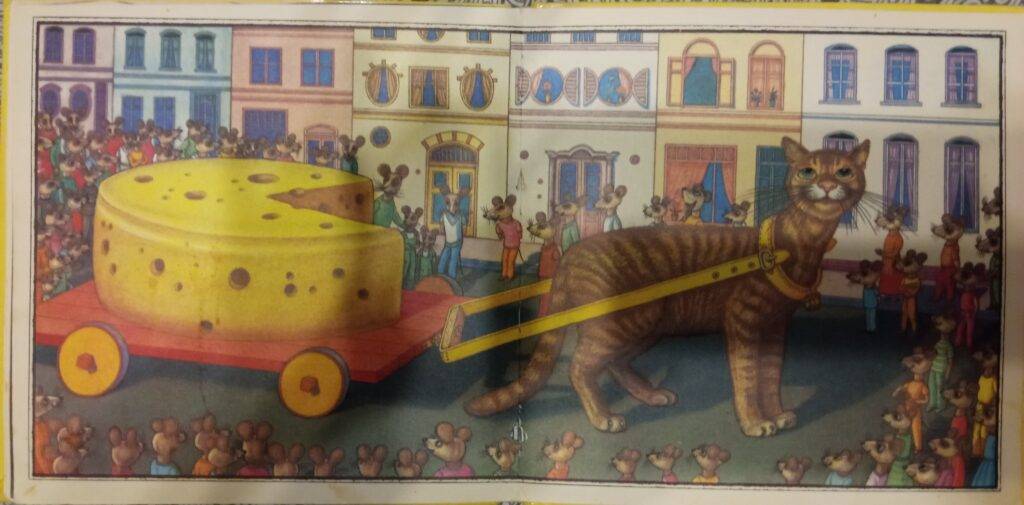

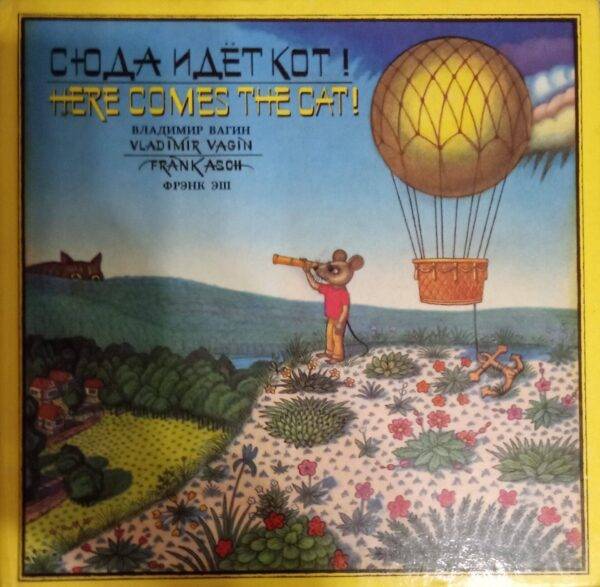

That part I actually remember. The Soviet people wanted peace more than anything else. And whenever we would notice improvements in the geopolitical situation, we were happy. Do you remember Samantha Smith? We do. I also remember the so-called Child Disarmament: kids were encouraged to give up toys that mimicked weapons. Soviet kids would get pen pals from the West, in particular, from the States in the 1980s. I still have a children’s book for preschoolers/elementary school children learning English. It was a bi-lingual comic called “Here Comes the Cat!” co-created by a Russian and American artists in 1989.

The Soviet people wanted peace and agreed to back off hoping that the West will do the same (non-expansion of NATO, for example). It was not about us losing the Cold War, it was about us longing to stop it. Then, around 1992, we learned that we lost it from the Western sources. Nice.

Finally, what destroyed the USSR.

I think you have all heard that there were protests around 1989. But what you probably don’t know is that those protests were not about disbanding the USSR, they were about making the Soviet Rule Soviet Again (soviet, совет = council, i.e. power of the people’s councils, most democratic thing ever, if you think about it). What happened later is yet to be researched. Most likely, it was a combination of treason and manufactured consent (I learned the term from Ian, actually). There was a referendum and the Soviet people voted against disbanding the USSR, but people in authority decided otherwise.

The 1990s followed. Some say the USSR was dissolved peacefully. No, it was a bloodbath with ethnic conflicts rekindled or started around the former USSR and beyond, with about 20m people in Russia alone not surviving the wild reforms and with life expectancy dropping, with ethnic Russians left outside Russia making us the largest divided people. So when I have recently heard that Russia did a very good job building capitalism, I could only sigh. Actually, our current economic strengths come from what was preserved, e.g. vertically integrated state-owned companies like Rosatom, Roscosmos, Gazprom, state-owned metro, power grids, etc.

To sum up, I would say that the USSR was a beautiful attempt of the people to build something better. I call you for respecting this attempt. Don’t be an ignorant moron or a professional Russia-hater on payroll like Julia Ioffe.

I envy Ian.

I hope he is happy here. It’s not easy, a lot of changes for him.

Having followed Ian’s Dad for 20 years and then meeting Ian has caused me to acquire affection for both and you as well. I have learned so much from you. I’m grateful to both of you. You make a handsome couple.

I thought a couple extra additions from a likewise Russian perspective could be useful (am Russian, am in Russia, though I was born at the very end of the USSR so could not know it in person).

On prison camps – the interesting thing here is just how distorted the whole idea was by hostile US propaganda. Prison labour is basically the most Russian-penal-system thing ever, if anything “simple” prison of keeping someone locked up in a cell for ages sounds like pure petty vindictiveness to most of our fellow Russians who ever touched that subject. In monarchy times prison labour was called “katorga”, which sounds suspiciously Tatar in etymology to me (I haven’t researched the word yet, just the sound of it) so is likely a borrowed format from the Horde; some people may know Dostoyevsky as one of the most famous inmates of such. They weren’t pleasant places to be but they were never meant to torture-murder people, they were just forced labour facilities doing things like mining, digging or logging. Bolshevik powers simply continued operating the same prison labour system, and had a lot more prisoners to handle with the whole Civil War shebang. Most Westerners don’t even seem to know that “GULag” is not a Russian word but an abbreviation for “Main Directorate of [Prison] Camps”. And that’s all they ever were – prison labour camps for convicts, not meant to kill or forcibly brainwash them. Over time, camps gave way to better-established prison facilities and prison labour could be more about simple manufacturing than outdoors hard labour, and this system continues today, they’re simply not called “camps” anymore.

But that doesn’t sound villainous enough for propaganda purposes, does it now? After all, the US loved its prison labour more than Russia ever did, chain gang culture being a ready example; Britain outright sent people convicted for petty charges to hard labour in Australia as a deliberate policy of populating it, and so on, and so forth. The US continues to have by far the biggest prison-industrial complex in the world to this day, far eclipsing Russia’s. So as part of the “Cold War”, we saw propagandists trying to demonize the USSR simply lift the concepts of Nazi German death camps for POWs and Jews and transpose them onto the USSR, and that’s how the concept of “the gulag” was born. Nowadays I see American conservatives online speak about Nazi death camps and USSR prison camps as synonymous and the same in principle.

An underappreciated aspect of the whole “purge” thing is that it was not evil Stalin killing and jailing people for fun, but a bitter intra-Party struggle for power and direction of the Party and the nation by different factions. And all those factions tried to wield the judicial apparatus as a maul in that fight. Of course, that’s sensible (if grim) as opposed to being a clear-cut black-and-white “mad commie tyrant” story as sold to us by the likes of Solzhenitsyn, so we couldn’t have that during Perestroika. I believe we will yet live to see the truth reassert itself in this.

On consumer goods – I will relate a curious observation my parents and their similarly-aged relatives shared with me and corroborated among each other. They were all born in mid-to-late 1950s, and all remember the 60s as a time of general plenty; as an example, my mother hails from a small village in the Smolensk region that was hit hard by the war (Banderite irregulars serving the Germans did the worst damage there, as it happens), and she not only noted that there were no signs of the devastation in their village that she could see as a kid, but also that they had things like fresh “exotic” fruit (i.e. things not normally growing in Russia, such as pineapples) available at all times, and at affordable prices, in the store they went to for supplies throughout her childhood – until the range of goods and produce somehow quickly started shrinking and worsening in the 70s. Even after they moved to the city in that decade, her family did not see the same level of plenty as they knew in a backwater region of the Smolensk area.

As a tangent on both these things – the now much-ballyhooed idea of “Stalin engineering famines to kill minorities and proud Ukrainians!” is of the same ilk as “the gulag” one, and again the truth is simpler and of very 1920s-30s grim-calculus-of-life nature. Industrialization cost money, resources and workforce, and the USSR had to sell its grain surplus and reserves for cash to keep it going – so when famines occurred in broad swathes of the USSR due to droughts and knock-on effects of losses from WW1 and the Civil War, there was little recourse to turn to. It was basically a “we have to make an industrial breakthrough even at this cost, or we’ll get crushed as a nation” decision, and the risks did end up occurring and hurting us. The present-day Ukraine was not even the hardest region hit by famines – that would be the Russian North and Kazakhstan, all of those had crop failures occur during times of lacking food reserves due to the need to sell them to keep industrializaiton going. In the short term, this created suffering, but without the industrialization, the USSR would have been crushed by Nazi Germany – so Stalin’s words about industrialization that I paraphrased above turned out to be all but prophetic. There were no “engineered famines to kill people”, it was a grim decision made to ensure survival and ability to develop in the future. Coincidentally, capitalist Imperial Russia did this all the time, selling the better part of its harvest to Europe even when there were food shortages in its own regions to finance something, it just wasn’t usually so life-or-death important.

While I cannot personally attest to what I’m about to say due to not having been there in person, I’ve grown up with all these events fresh in the minds of people who were all around me, and it honestly feels like the biggest cause of USSR’s demise on the people’s side was… naivety. The Soviet people were too optimistic and trusting, almost childlike in ther belief that the West wants peace and love and brotherhood among nations just as much as they did. Meanwhile, over in the West too many people were certain the Soviet population were zombified slaves programmed to hate the West at the very same time.

Final word on the way Russian/USSR words and terms are handled in the Anglosphere – I feel like many translations/transliterations made of them were deliberately designed to obfuscate or create a negative image. The word “Soviet” is the most ready example – it actually sounds like “sovet”, there’s no “ee” sound in it, but it was made to sound more unpleasant and harder to pronounce to invoke that sweet Black Speech angle. Compare and contrast how Afghans simply called it “Shura”, i.e. “council” but in Arabic – personally, I always thought “Shuravi” (people of the councils) sounds a lot more human and explanatory for what it stood for than the “scary alien” word Soviet. Just as important, though, is the Russian name for the part of WW2 between USSR and Germany – the English translation using the term “Patriotic” gives it connotations of propagandistic officialese, but in Russian the term for it is “otechestvennaya” (Fatherland/homeland), same as the war of 1812 but greater (hence Great). So the words “Great Patriotic War” invoke the image of fake Soviet propaganda in the West, whereas the actual Russian term has none of that and simply denotes it as the Greater of the two Homeland (existential for national survival) wars. There are more words like that, those are just two easy examples.

Sadly, though, I think this was and is to many people’s liking. Very few Westerners I’ve ever dealt with (and I’ve just written a huge comment in English here, so you can imagine I interact with English-users a lot for a long time now), in general, are interested in seeing Russia as “a normal country, a place where there is a mean average level/proportion of human happiness and unhappiness”. Most Westerners actively desire to see Russia as a sort of “evil Other” to contrast their own goodness against, or as a moral fable about the evils of whatever it is they hate (lefties claim Russia is evil because it’s conservative and hates diversity and freedom, conservaties claim Russia is evil because it’s a commie hellhole and hates capitalism and freedom). All too many resist it and want to hear none of it, considering any talk about it “Putin propagandist lies”, because to see us as just another nation and people would break a very convenient Hollywood-tastic worldview with a struggle of good and evil peoples, or simply a provincialist one where the “normal” people only live in the familiar West, and outside of it things are abnormal and wrong. The latter in particular is a base human insularity instinct, and I’m sad to see it’s so normal in a formerly “enlightened” culture the West represents – cultural development should overcome it, not encourage it.

Good points, thank you

This article and the beautiful reply above are music to this English speaking Britisher with a Slavic spirit. Thank-you Maria and ‘Red Outsider’ from my heart. More please!

Ian, thank-you for your blog which along with Yalensis at Awful Avalanche is one of two of my favourite daily reads. 🙂

QK

On GULAG and forced labor facilities > the funny thing is that right now the US has the very same forced labor system as the USSR had. It’s just that some of those prisons are privately owned and run and thus the profit from the inmates’ forced labor is flowing into private pockets.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prison%E2%80%93industrial_complex

By the way, I don’t understand what’s wrong with prisoners working. I don’t mean some terrible logging camp from a nightmare where people starve and work in the worst possible conditions, but labor in general. It is better than just sitting in a cell, really. A young person can acquire valuable skills. Also, it’s not totally unpaid. And, it is a part of compensating the damage that was incurred from a crime. So, overall, it’s not necessarily bad, as long as it is not plain sadistic.

> overall, it’s not necessarily bad, as long as it is not plain sadistic.

In theory I don’t see any problems with forced labor done by the prisones either. As you say, some kind of compensation for the damage done to society.

In reality that last part of your assumption is almost always missing from such systems, seeing as the prisoners don’t have many rights and even less ways to exercise the ones they’re supposed to have if those are denied to them.

good points, both of you.

Katorga is a loan from Greek katergon “forced labor, galley slave”, mentioned at least since 14 cent. in Novgorod [Max Vasmer, Etymologie of the Russian language, in Russian transl. by Trubachev]

I wish to make a few remarks and I’ll keep them succinct.

On consumer goods not being available in the Soviet Union; I don’t know if you’re just being ironic about dresses from western fashion magazines but the most basic goods were not regularly available everywhere in the Soviet Union. People were allocated staples, you couldn’t just rock up in a store as the shelves were empty, you’d have to wait for when a delivery was made, same with cloth or fabric, this was not readily available and again depended on a delivery. At some point, I don’t know which year, state enterprises distributed Bread, Sausage and a quart of Vodka to workers on Fridays creating an alcohol dependency problem which exists to this day but is being dealt with by the Putin administration. It’s the reason Aeroflot doesn’t serve alcohol on domestic flights for example.

There was an exception to the above and it belonged to the party members who could buy subsidised goods in the party store; everything was available for them at all times, I know it as the Comecon store probably named so in Comecon member states . As a party member of good standing you could even order a car or apply for a holiday somewhere with restrictions. In addition there was a black market and if you had the money, you could buy goods there.

On corruption, this was all encompassing; a staffer for a state enterprise would bribe a senior staffer for certain privileges and he or she in turn would bribe a yet more senior staff member and so on all the way to the top. I had a friend in Tashkent who was a millionaire from all the bribes and black market trade. So, if you had money and status in the party, you could have a grand life in the Soviet Union.

One thing that I don’t consider particularly attractive when told about it was that everyone was spying on everyone else, a more or less permament proletarian lifestyle audit so to speak. This system was clearly encouraged by the authorities to gather intel on its citizens, a bit like people in the EU during Covid on who was or wasn’t wearing a mask. You could be denounced if your thoughts and the expression of such thoughts were considered counter revolutionary, you might find yourself asked to come for an interview at the local party office to explain. Economic offences could also thus be recorded so it is a bit of a two sides to the story, I’d accept a milder version of social control.

On the dissolution of the Soviet Union, you don’t have to research far nor in the future; Stalin’s secret protocol in the Ribbentrop / Molotov agreement brought down the Soviet Union. The Estonians obtained a copy of the annexation agreements for the Baltic republics which had the proviso of needing to be ratified by the Supreme Soviet but never were. The Estonian delegation petitioned Gorbachev for independence referring to this ‘secret’ protocol which he refused to countenance. I remember Russian troups being sent to Estonia as they were going to proclaim independence unilaterally, these events precipitated the military coup against Gorbachev which saw Yeltsin of the RF rise to prominence in his opposition on the streets of Moscow culminating in the shelling of the house of deputies and the subsequent failure of the putsch attempt resulted in the vote for Estonian independence being supported by the other states but notably by Yeltsin’s Russian federation after which it too proclaimed independence from the Soviet Union.

I don’t have a problem with the people of Russia wanting a better life and peace with the West. They succeeded in uplifting themselves from serfdom under the Czars bringing education, equality and industrial development. Some general secretaries of the party were more successful than others in procuring consumer goods and provisioning better housing and more personal freedom.

In my opinion, it’s a pity that the Soviet Union could not reform itself without dismantling the entire state as it left it wide open to exploitation by the West, giving it an unearned “victory”. The old Soviet leaders really believed in the sanctity of international law and agreements whereas by contrast the “new” West of the malignant EU and warmongering US do not, they only seem to and only when faced by the formidable opposition of the Soviet Union.

Disclaimer notice:

For my sources, I have my family who are citizens of Bulgaria and friends who left Uzbekistan & Azerbaijan after independence. My now deceased uncle used to travel freely throughout the Soviet Union and Comecon countries and used to regale us with stories of foreign lands. I personally traveled to the Balkan.

People now miss those staples, so good they were). It became really bad only in late 1980s and I actually remember it. Otherwise..I have hundreds of pictures of my family from 1980s, some taken in the apartment we got from the State..we were ok). Neither of my parents was in the Party, mom was from the working class, dad from “inteligencia” (no party members in the family either).

Speaking of my irony…well, what we have obtained, all that glossy stuff, is definitely not worthy of what we have lost. And I’m not speaking about money value. It took us several decades and a world war to become Russians again.

Very interesting article and interesting answers. I grew up in a family that for some (to me) unknown reason feared the USSR. We are Swedes & Danes so not sure where it originated from, but when you are told to fear something as a child (I was born in the late fifties) it stick even if you as a grown up have no rational reason for it. When the USSR no longer existed Russia became the thing to fear because we learned that you couldn’t trust Russia regarding anything. It wasn’t until the special operation in Ukraine that my eyes (and mind) got wide-open for how heavily brainwashed I and other people in Europe are regarding Russia. When all ISP in EU got orders to not allow access to any main Russian information webpage this false narrative really crumbled down for me personally. Life gets very interesting when you realize that many things are not at all what you thought they where.

> Life gets very interesting when you realize that many things are not at all what you thought they where.

Interesting, yes. But also pretty terryfying. Cause once you realise that kind of thing it’ll make you question your basic beliefs about other things in life too. And that’s not a nice feeling, it fells like you thought you were on hard ground but suddenly you find out you’re in a swamp.

Which is why a lot of people will keep avoiding facing this side of reality – it takes both guts and a pretty stable psyche to take that kind of change in stride.

I’m talking from experience here. The people who were born and raised in the USSR – we all had to face that paradigm shift and back then there were millions of people who just coulnd’t take it, this break off from everything they were raised to know and to believe, the world just changing rapidly and leaving everyone to scramble trying to catch up.

I went through exactly what you describe. The process began years ago when Ian’s Dad, Larry Cummer wrote about the lies of our leaders.

I’m 68 and arrived in the USA in 1961 at the age of 7 1/2 from the Netherlands. We loved the USA before coming here because of our gratitude for saving us from the Nazis. My parents and grandparents told me about Zhukov and Chuikov. They did not hate the Soviets and knew of the suffering in the East.

Therefore I hated the Communists but not Russians. I was conditioned, programmed. I now understand America is the most propagandaized nation on Earth.

The USA needs to accept multipolarity and assume a defensive posture. Instead of contention, competition in doing good in partnership is the way forward. Great powers are ascending, namely Russia, China and India. Imagine what can be accomplished.

Currently NATO is a Suicide Pill for the World and that’s why I hope Russia wins.

I get that it can be terrifying and I absolutely understand that it can shatter peoples life. It does for many, no question about it. But I have been on a slow but steady path of waking up to a different reality since 2011 and you get used to be thrown off your feet time and time again after so many years. This awakening around how very deep the lies run and how utterly false the narrative is that your government (and the main stream media etc) is feeding to you was just the last icing on the deep state fake cake. That is why I see it as interesting more than devastating when I remove yet another layer of this false global narrative.

There is a line in the old song Bobby McGee that in my opinion is very true.

“Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose”

It is first when you have lost every layer of fear that you are truly free. At that point nothing can really rock your boat. I think many of us are very close to that point and thus find life more interesting than scary.

Nice article, and nice comment from Red Outsider, too. I have first hand experience in this, I live and have been living in Hungary from the early 70s, so as a young adult, I could see the end of the system. At that time we hated it. But what followed was a catastrophe in almost every respect. It was sobering. Now I (and a lot of my compatriots) have healthy respect for the socialist system (for Westeners: they never called it ‘communism’). As Red Outsider noted, the 70s (especially the end of the decade) was the the beginning when we felt the problems with economy. These were the main reason why people thought (now we know, erroneously) that capitalism was better. Those problems look ridiculous in hindsight, capitalism produced far worse problems and Western world is in recession from actually the dot-com bubble. It turned out that the welfare state was welfare for a small portion of the capitalist world, the rest got neocolonial exploitation, and even in that small portion it was more like an answer to the soviet system, and when that was gone, welfare was no longer needed. Ah, yeah. Democracy. Such a meaningless, ineffectual thing… It suspiciously looks like we have it for the looks only. The same with the freedom of speech. You are free to say anything as long as it doesn’t count. Otherwise you get crushed pretty soon. And the Market that knows everything, the Hidden Hand. What a ridiculous bs in the age when we have the most extensive communication system in the world, paired with the most advanced computing power. FYI, central planning was quite good even when the mechanical typewriter was the most advanced office accessory.

What a thread this turned out to be! Maria’s post is great and so are the comments.

Thank you all.

Very best regards!

I’m English.I came to the USSR in1989, studied for 1 year at Voronezh State University, went back to the UK in June 1990, came back to Russia – the Russian Federation in 1993, and have been there ever since.

Until 1984 I worked as a coal miner in the north of England. Then came a year-long strike. I was fired, dismissed, blacklisted. My union paid for me to study. I studied German in Germany for 1 year and Russian for 1 year in the USSR. It was just fate how I came about to study these languages, but I intended to live and work in Germany after my having graduated in the UK in 1991 and also completed post-graduate studies in 1993. But I was still unemployed in 1993, so I set of for Russia to work.

I had grown tired of Germany by the time I set off for the USSR, but I immediately fell in love with Russia and the Russians, despite the fact that I experienced the last years of Gorbachev’s perestroika and the awful ’90s of the “fast track to capitalism” in the ’90s. In the 1997, however, I met and married my wife, a Muscovite, who has borne me three wonderful children: Vova (23, now married”), Lena (22, still a student), and Sasha (nearly 15 and still a schoolgirl).

My old life ended when I was 36: my new life began in 1993. I never want to return to my native land: I have only been there on very short visits: 5 times these past 30 years. The happiest days of my life have so far been those that I have spent in Russia.

I am not a wealthy man. I earn about 35 000 rubles a month. My wife is the breadwinner.

I am 74 in 4 days time.

Soon I shall move to our dacha, where I shall probably live until October. It is situated 85 kilometres south-west of Moscow. Soon I shall be listening to the nightingales that sing in May in the forest next to our little country house.

“The past is another country” an English writer once said. I agree fully: I cannot go back to the past, nor do I wish to do so, and I have no wish whatsoever to return to my mother country. Russia is not my Motherland, but Russia is my adoptive mother. She has been very kind to me.