In light of present and recent circumstances—the ongoing war in Ukraine, the decades-long expansion of NATO, and the many claims of Russian interference in American elections—Russia and her actions (as well as the Western reactions to them) might seem to be of the most obvious interest to would-be prognosticators intent on envisioning the world of 2050 and beyond.

The thesis of this section: They—think-tankers, strategists, economists, and financiers—would be wise to put down their fortune telling cards and tarot and pick up a set of oracle bones.

A war with Russia has the potential to be an existential threat to the United States, NATO, and any country too closely tied to the economies of either. But the threat of Russia is easily described and avoided. All we—Russians or Americans—need do to avoid nuclear conflagration is learn to stay out of each other’s way. Our economies are not tightly integrated, and our social, educational, and cultural connections are so weak as to be meaningless. Like neighbors on the worst of terms, we can resolve our difficulties by way of avoidance. We need but to have the shared boundary of our properties carefully surveyed, erect the most imposing of privacy barriers, and avoid any acknowledgment of our detested counterparts when we drive directly into (or out of) our garages. Good fences make good neighbors. Forgetting as much may cost us our lives. Remembering as much is easy. If we are wise enough to choose the latter over the former—if we are prudent enough to overcome the bellicosity of our national spirit—remains to be seen.

In the previous essay, we considered the tendency of Americans to see all problems through the lens and metaphor of war. Language shapes thinking, shapes language. And this relationship is more significant and more fundamental than we may realize.

Every metaphor is a narrow-angle lens, but that of war is more so than most (a point we considered in the previous essay), occulting anything that cannot be identified quickly and from a distance as friend, foe, or materiel. Yet Russia’s vast expanses are singularly observable, if occasionally overwhelming, assuming we choose to scan the horizon.

China is different.

This truism is as easy to accept as it is to ignore. The manner and degree to which the United States and China differ cannot be reduced to the single issue of religion, race, or historical development. Rather, China is so unlike the West that the only way we—the occidental peoples—can hope to understand it is through methodical effort. Thus far, we have failed miserably in this endeavor, and this is, for reasons presently considered, at our peril.

This essay is the culmination of my modest efforts to better understand the Chinese perspective, how it has been informed by history, and how it will evolve. This essay (and the series of which it is a part) has been written to promote understanding and tolerance, if not necessarily goodwill, across cultures in an increasingly complex geopolitical climate. I am neither scholar nor expert. I write because I have found that others either ignore the issues and the history addressed herein or use their knowledge to promote elite interests and brinkmanship.

It seems that there are only two people ready to grab this most irascible of bulls by the horns—me and nobody. I would have asked nobody for help, but it seems he got the hell out of Dodge.

Despite the preceding bloviations, I have neither posed nor answered the critical question. I have only established that our connection to Russia is weak and that the tools for avoiding war with her are readily at our disposal. Now we must consider this:

Why China?

As the one real and immediate economic competitor to the United States (with India being years behind), China is an obvious choice for study in the fields of finance and trade. What is less understood is that China, unlike most other Asian states, unlike Russia, unlike the Middle Eastern nations, unlike any other technologically advanced nation, has a cyclical relationship with outside cultures.

The Chinese periodically allow intense cultural exchange between their educated classes and the elite of other countries, followed by much longer timespans in which the nation is effectively closed to the world except for limited (and strictly overseen) trade. Thus, the Chinese understanding of the West (and the Western understanding of China) is more informed by periodic snapshots than by a continuous video stream. The Chinese have their bouts of xenomania. The peoples of Europe and the Americas will occasionally find Chinese things or traditions fashionable, cool, or somehow resonant with the tensions and struggles of the age. Or they may declare some aspect of China—her people’s work ethic or her superior mathematics education—worthy of emulation. (And we are each willing to copy each other’s cuisine, although not always to the highest degree of fidelity.) But beyond these glancing moments of mutual interest, the Chinese and Western peoples are effectively (if imperfectly) segregated for years on end. Skepticism of cultural imports is not unique to China. And Asian fears of having their culture supplanted or corrupted by imperialist Western influence are not unfounded. And we will address what China can and likely will do to mitigate this risk later in this essay.

We continue with a statement will we consider (with variations) more than once in this essay: A nation’s strengths can also be her weaknesses.

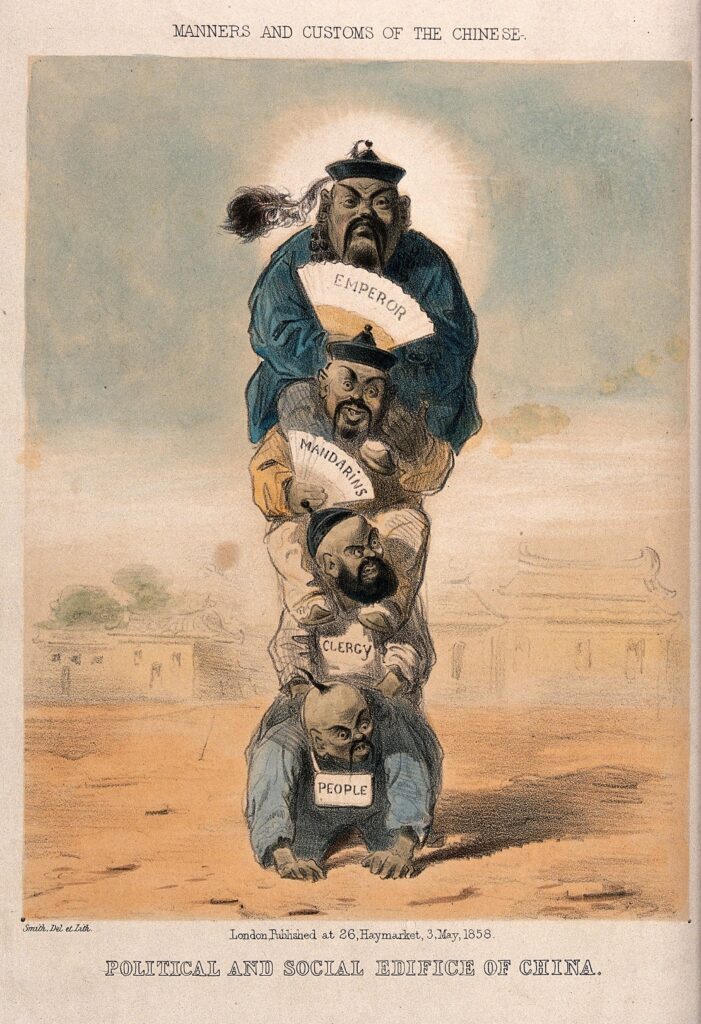

The mandarinate—China’s bureaucratic corps, trained and tested in Confucian philosophy and principles of governance—has been a unifying force in China for at least 1,000 years, when it supplanted China’s earlier system of extensive hereditary nobility. And since the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), during which public schools were established to train examination candidates unable to afford private instruction, it has provided a means of meritocratic social advancement for freemen of every social station. This was a great strength.

The mandarinate’s highly demanding entry standards, rigid hierarchy, and intense emphasis on scholarship made it a bulwark against the political upheavals Europe experienced throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. These same traits allowed the mandarinate and its civil service system to channel the energies of men who might well have otherwise disrupted the social order. As did this system stabilize Chinese society, so did it make the society dangerously resistant to change. Such is a major reason China found herself behind the Western powers by the beginning of the First Opium War (1839-1842 CE), in which the weaknesses and primitiveness of the Chinese army became undeniable.

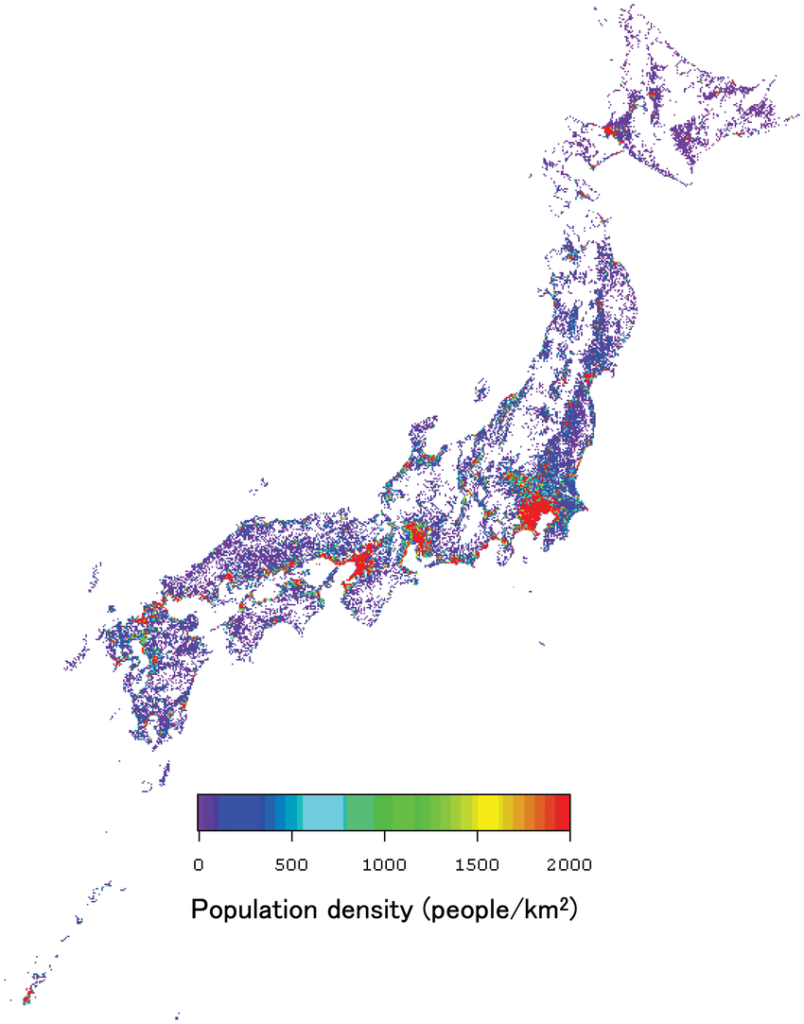

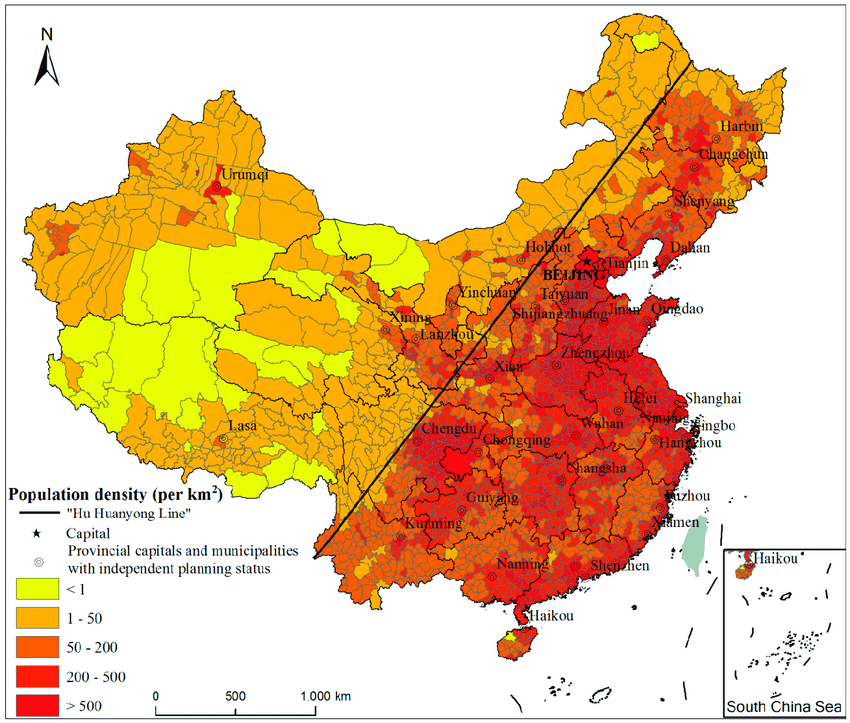

A significant difference between China and Japan (probably the most culturally similar of China’s peer nations) that made the former’s path to modernization rockier than that of the latter is China’s massive interior.

Japan is settled moderately along her outermost boundaries, somewhat less densely inland, and sparsely on her central mountain ranges.

China, however, is settled in such a way that foreign cultural influence can do little more than break along the shore before being pushed back by forces from deep within the country. As late as 2015, China still had a significant number of people living inland, far away from more Westernized coastal regions and cities, including Shanghai, which was famous for its jazz clubs and cultural openness throughout the 1930s.

This large interior population served (and continues to serve) as a reservoir of Chinese traditional culture. Even Chinese who move to the cities rarely lose their bonds to home. Many workers and students in the major metropolitan areas undertake the herculean task of returning home every Spring Festival, during which time they catch up with family and renew their connection to their home province. This yearly journey, which collectively constitutes the largest recorded migration of humans, both demonstrates and reinforces the Chinese commitment to sustaining extended family and community relationships. It slows the transition of Chinese identity from the relational and collective to that of homo economicus—the West’s consumerist, commoditized New Man (and Woman).

Cycles of Openness/Cycles of Closure

The Chinese tendency to alternately open and close their borders and culture to non-Chinese influence was previously mentioned, and the interplay between urban and rural populations was suggested as a cause for this. But the timing and patterns of this relationship would benefit from further elucidation. Consider the list below, a profoundly incomplete summarization of some of the most significant events in China’s cycle of openness and closure over the last 1,500 years, from the Tang dynasty to China’s Communist/Nationalist civil war (1949).

- Tang (open era/golden age of Chinese civilization) (618-830s)

- (630) Gaining of territory in Mongolia

- (712-756) Reign of Emperor Xuanzong (Regarded as a golden age of Chinese art, culture, religion, and cosmopolitanism)

- Tang (closing/declining era) (840s-880s)

- 840s Persecution of Buddhists (Led to decline in religious and cultural freedoms)

- 870s-880s The Huang Chao Rebellion and subsequent execution of poets (Destroyed cities and established declining respect for the arts)

- Ming (open era) (Early 1400s)

- Zheng He’s treasure ship voyages (Increased global trade and exploration to as far away as Africa)

- Ming (closing era) (Mid-1400s-1500s)

- (1430-1470s/1525) Banning of oceangoing voyages, destruction of Zheng He’s records, and burning of the last of his vessels (Ended most international trade and protected local industries from competition/influence)

- Qing (mixed era) (1644-1912)

- (1684) Establishment of merchant guild trade system (Allowed Qing to collect taxes on imports)

- (1689) Treaty of Nerchinsk (Defined Sino-Russian border, facilitated commerce)

- (1755–60) Expansion of China under Emperor Qianlong (Defeated Mongols and Turks, conquered Xinjiang)

- (1757-1842) Designation of Canton (Guangzhou) as China’s one international trading port (Greatly restricted foreign trade and influence)

- (1839-42) The First Opium War (Evidenced the weakness of the Chinese military and failed to stop the flow of drugs into China and concluded with the Treaty of Nanjing, which undermined Chinese sovereignty and remains a sore point in modern China)

- (1850-1864) The Taiping Rebellion (Led by Hong Xiuquan—a would-be civil servant who believed himself to be the Chinese son of God—and caused by the loss of the First Opium War, the influx of Christianity, and anxiety over China’s apparent weakness. Ended with more than 20 million deaths and resulted in a reactionary response by Qing)

- (1856-60) The Second Opium War (Ended in loss and humiliation for China and the unrestricted flow of drugs, religion, and foreigners—who were not subject to Chinese law—into the country, all of which were forced upon China by way of the unequal treaties)

- (1860-1874) The Tongzhi Restoration (Strengthened the Qing dynasty and extended its life, without implementing reforms of magnitude undertaken during the contemporaneous Meiji Restoration of Japan)

- (1898) The Hundred Days of Reform (Failed effort at modernization confirmed that the Qing dynasty was unable to adapt to the modern era)

- (1900) The Boxer Rebellion (Largely consisting of peasants from deeply impoverished Shandong, the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists blamed international influence and colonization for their dire straits and attacked foreigners, foreign properties, and Chinese Christians. Resulted in a crushing defeat by an eight-nation force and a weaker Qing dynasty)

- Republican/Interregnum era (open era) (1911-1949)

- (1911) Xinhai Revolution and establishment of Republican government (Established a nominal government, influenced by foreign ideas and Chinese returning from overseas, but failed to unify country)

- (1916-1928/1949) Warlord era (Resulted from the extreme weakness of the central—Beiyang—government. Nominally, ended in 1928 but not effectively ended until 1949, when the Communist government assumed power. No effective control of immigration during this time)

- (1937-45) Second Sino-Japanese War—The Second World War (temporarily paused hostilities between Communists and Nationalists while encouraging a strong sense of national identity and resentment of foreign influence)

- (1943) End of extraterritoriality for British in China (Terminated right of many British to do as they pleased in China)

- (1949) End of civil war/Founding of People’s Republic of China (mixed/closed era)

- (1949) Founding of the People’s Republic of China under Mao Zedong

More than one lesson can be drawn from reviewing the above list. First is that the openness/closure cycle of China predates the current government by more than a millennium. Second is that reasons for China’s periodic closures came about for a variety of reasons: 1) government policy to preserve the status quo or in response to internal political stresses (the burning of Zheng He’s treasure ships in the Ming dynasty), 2) government reaction to foreign attack/assaults on sovereignty/perceived threats to Chinese national integrity (the Qing dynasty restrictions on foreign trade to Guangzhou), or 3) popular sentiment (the Boxer Rebellion in the late Qing dynasty). China’s periods of openness can be attributed to reasons no less varied.

A critical point: The people of China have not proven powerless in determining the extent to which foreign influence and investment are tolerated in their country. The theory that China’s closures were purely the result of designs by the elite to isolate their subjects/citizens can be debunked by a cursory review of the historical record. No Chinese regime has had completely free reign to disconnect China from or integrate her into the world. When the government proves too protective of the status quo, the people eventually rebel and demand modernizing reforms or a loosening of restrictions. When the government is too accommodating of outside powers, resentment grows, and the Chinese take it upon themselves to stand up, sometimes with extraordinary violence, against foreign meddling, foreign meddlers, and any Chinese unfortunate enough to have been caught supporting either. This has remained the case, at last partially, up to the present day—something we should keep in mind when considering more recent history.

Sungmin Cho categorizes Chinese cycles of openness and closure using slightly different terminology—fang (放: relaxing) and shou (收: tightening)—and describes the history of China from 1949 to the present using these terms. His divisions are as follows:

- Nation-building Projects (Relaxing) (1949-1957)

- Great Leap Forward (Tightening) (1958-1961)

- Pragmatic Adjustment (Relaxing) (1962-1965)

- Cultural Revolution (Tightening) (1966-1978)

- Reform and Opening Up I (Relaxing) (1979-1982)

- Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign (Tightening) (1982-1983)

- Reform and Opening Up II (Relaxing) (1983-1986)

- Anti-Bourgeois Liberalization Campaign (Tightening) (1986-1987)

- Reform and Opening Up III (Relaxing) (1987-1989)

- Neo-totalitarianism (Tightening) (1989-1992)

- Soft Authoritarianism (Relaxing) (1993-2009)

- Hard Authoritarianism (Tightening) (2009-Present)

Cho’s analysis provides a useful timeline; however, reliance upon it may cause one to underestimate the influence of the people of China in determining their fate. One may come to see them as being victims of grand government schemes, not active participants in the process of policy creation, which they are, although not necessarily through formal means. A case in point is the Cultural Revolution, the dynamics of which were examined in some detail in the first essay of this series. While Mao Zedong was the instigator of the Revolution, he was not the sole motive force. Youth participation was so widespread and so vigorous (to the point of young people calling—sometimes successfully—for their parents to be shot) that he grew alarmed. And his effort to calm the waters of rebellion by sending millions of youths to the countryside was not of much effect, with the political disorder continuing until Mao’s death.

This does not establish that the government cannot actively oppress popular desires for modernization and global integration. It has and can. Rather, China’s cycles of openness and closure—or relaxing and tightening, as Cho calls them—are not always exclusively the product of orders from on high (in the modern era or earlier eras).

Cho’s analysis focuses more on the political than the economic. Despite changes in cultural policy, the Chinese government has worked consistently to forge an export economy since at least the establishment of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in 1980. The establishment of the SEZ allowed a once unremarkable fishing village near Hong Kong of around 30,000 people to become one of China’s most populous cities as of 2020. And before the COVID lockdowns, none of the many political changes in China interfered with the free flow of goods from Shenzhen, the world’s factory, to ports of friend and foe alike.

China is moving away from reliance on international trade. This is part of her long-term goal to increase “internal circulation,” meaning the design, production, and consumption of goods within China—relying less on foreign markets by the year. The much-discussed Made in China 2025 initiative is intended to decrease Chinese dependence on foreign technology and engineering. But this is part of a longer cycle of policy evolution in China, which oscillates at a lower frequency and with far greater stability than the political cycle described by Cho.

But none of this diminishes Cho’s assertion that China is in a period of closure/tightening, which is unlikely to see a sudden reversal. Cho’s prediction and the one made by this author—both of which will be addressed later in this essay—are similar in span but different in the methodology used to devise them.

Finally, there is the matter of a component of China’s economy, politics, and culture not addressed in conventional market projections or by Cho’s political analysis—her foreign language and overseas education markets. A review of trends in this domain supports Cho’s argument, in summary, if not completely in its mechanics.

Slow, Inexorable, Complex: Waves of Educational Policy in China

Changes to educational policy in China should not be taken lightly. This is a nation that has a god of examinations—one to which modern Chinese still pray. And the tremendous emphasis on education in Chinese culture makes trends within this sector an excellent barometer of official policy, economic conditions, and Chinese popular perceptions of the outside world. The primacy of education in China is also why the closing of almost all schools in China during the Cultural Revolution was historically noteworthy.

First, we will examine changes to law and policy in regards to foreign teachers, who constitute a relatively small part of a massive language-education industry. Next, we will consider changes, both planned and already implemented, to China’s foreign language educational requirements. After that, we will review recent trends in the number of Chinese students who wish to study overseas and the number of those who wish to remain overseas after completing their degrees. Finally, we will consider some of the factors that play into the decision-making process behind the last.

We turn our attention to the foreign teachers.

For almost 30 years (1985 to the end of 2012) obtaining a visa to work in China was reasonably easy, with working in East Asia—including China—becoming particularly popular with Western millennials after the 2008 economic downturn. There were educational, medical, background, and experience requirements; however, the enforcement of labor law was inconsistent, and working on tourist/travel visas was tolerated (if illegal) to a limited extent. In 2013, the visa system was radically overhauled. Although the overhaul did slightly liberalize permanent residence criteria, applying for a Chinese visa became grossly impractical in terms of time and money required to complete the process for almost anyone willing to accept a Chinese salary. And in 2019, restrictions on foreign workers increased further.

Some of these more rigorous policies were needed, and their implementation can be taken more as a sign of the maturation of government policies than as one of China’s closure. Processes for the verification of credentials and backgrounds (criminal and employment) were flawed, which allowed certain underqualified, impolitic, and flagrantly criminal people to work in China. More generally, skating by on questionable foreign credentials has been known practice of Chinese and non-Chinese alike in the country since at least the 1930s. Qian Zhongshu’s Fortress Besieged, a classic of modern Chinese literature set in that decade, incorporated an instance of this as a key plot point. The establishment of a systematic and reliable credential certification service is far more an aid to global exchange than an impediment. Yet when taken within the larger context of the last 10 to 15 years of legal, political, ideological, and cultural transformation, these implementations give supplementary heft to the thesis of this section. This thesis is, broadly speaking, the same as that of Cho: China is steadily withdrawing from the world, as she has been for some time, and as she will continue to do for several years.

Next, we look to changes in China’s public school foreign-language educational requirements to bolster our argument.

Two years after the reforms of 2019, the majority of online tutoring provided by teachers outside of China was abruptly banned. Nominally, this was to reduce the very real pressure on students to study after hours from a young age (and all the way through college) and lessen economic demands placed on parents to pay for private tutoring. Such has the added benefit of minimizing the exposure of Chinese students to foreign ideas and cultures—a goal the government has incrementally pursued for years. This prohibition changes the employment market for non-Chinese teachers, and it reflects a shift in the official values and narrative propagated by the Chinese educational system.

The history of English-language instruction in China goes back to the Qing dynasty. Training was largely provided by missionary-funded schools or foreign-backed colleges. Throughout the Republic of China/interregnum era, English-language instruction continued, with the government being too preoccupied with political instability and the Japanese invasion to draft a coherent policy on the matter. The Communist relationship with English has been more complicated. With the expulsion of almost all foreigners in the 1950s, English lessons were effectively banned and replaced with training in Russian. This continued until the Sino-Soviet split, after which English made a resurgence before the Cultural Revolution, during which time so much as casual use of the language might have caused one to be labeled a traitor. English as an academic subject was restored to pride of place after the Revolution, growing in importance until it became a compulsory course from the third grade in 2001—the same year China joined the World Trade Organization. A mere 20 years later, a Chinese lawmaker proposed removing English from the list of compulsory school subjects. This idea was received with more interest by the public than by education officials.

The role of government mandates in English instruction must be given proper note, thus the considerable attention to policy decisions in evaluating how much of a role the language has in China at any given time. The function of English in Mainland China is not comparable to that of English in Hong Kong, Singapore, and India—all former British colonies. Whereas in these nations/cities, English functions as a dynamic and nativized language (hence Indian English and Singaporean English being their operational dialects of English), it has remained an academic subject in China. It is sometimes used for international commerce, but it has little place in the larger community.

Assuming that China does not abandon English-language instruction altogether, a distinct China English will come into being if it has not already somewhat done so (a matter very much up for debate). This is a considerable if, with the present status and security of the language being uncertain. English remains a poorly acclimatized transplant to China, with its continued existence contingent on continued government support for at least a period of several more years. Were the government to deem ongoing study of the language unnecessary for the nation’s continued prosperity, it would fade from use and memory within a generation. China English would become little more than a museum piece—an interesting, irrelevant possibility of what might have become one of English’s most widely known (if rarely spoken) forms.

We are now nearly ready to consider the present condition of Chinese students overseas. But before that, we need a bit of context. Although the Chinese have studied (and continue to study) in Europe, Australia, and Japan in non-negligible numbers, we will focus exclusively on the United States. This is both for the sake of convenience and due to the focus of this essay series, which is Sino-American-centric. After summarizing the history of this relationship, we will consider the present state of affairs and probable future trends.

According to journalist Eric Fish, the movement of Chinese students to the United States can be divided into four eaves. The first movement began in 1872, when 120 boys were sent to schools throughout the country as part of the Qing dynasty’s Chinese Educational Mission. The Mission, while a well-intentioned effort to provide young Chinese with Western educations, was riddled with problems. First, the program was long. The students were supposed to spend 15 years in the United States (although the program was canceled after less than a decade). Second, efforts to maintain the young men’s bonds with their homeland—lessons in classical Chinese and Confucian philosophy—did little to prevent their Westernization and growing rebelliousness. Third, the Chinese students encountered discrimination both while living in the United States, where they were mocked and occasionally beaten, and upon returning home, where they were seen as traitors.

Next, the second wave.

Despite this decidedly inauspicious beginning, the Chinese resumed studying in the United States not long afterward, despite the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barring immigration from China and rendering her citizens in the United States ineligible for naturalization. This resumed flow of students was very much by American design. A considerable number of Chinese students in the United States from 1909 to sometime during or shortly after the Second World War were funded by the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program. (The exact date of the Program’s termination has proven difficult to ascertain, hence the uncertainty of the timeline.) The Program used money paid by the Qing dynasty as compensation for American costs and losses during the Boxer Rebellion and its suppression to pay for the education of Chinese in both China and at American schools, MIT amongst them. This was supposed to promote goodwill between the two peoples and lead to the creation of a Western-educated leadership class that would be more closely aligned with American interests than with those of the emerging regional power of Japan.

In practice, the effects were multifaceted. The Program had a lasting positive impact in China at least to the extent that it subsidized the establishment of Tsinghua University, which was (and remains) one of the most respected institutions of higher education in Asia. But the experiences of Chinese students in the United States were often disappointing and may have done more to turn them against America and her values than in favor of either. The Program did nothing to stop the rise of Communism in China or prevent China from closing herself off from the world after the rise of Maoism. And as was the case for those who participated in the Chinese Educational Mission, graduates of American colleges in this cohort were regarded with suspicion when returning home, including abuse during the Anti-Rightest Campaign and the Cultural Revolution.

From that period—the late 1950s to the late 1970s—Chinese students in the United States were rare, at least partially due to most Chinese schools being closed and few, if any, students being prepared (or allowed) to leave the country.

The third wave of Chinese students in the United States began five days before the resumption of normal diplomatic relations between the Mainland and the United States. This day (26 December 1968) is when 52 students departed China for universities around America. The third wave continued until the Tiananmen Incident, after which Chinese graduates of American colleges were seen as enough of a threat to the political stability of the country that many were (if briefly) discouraged from returning home.

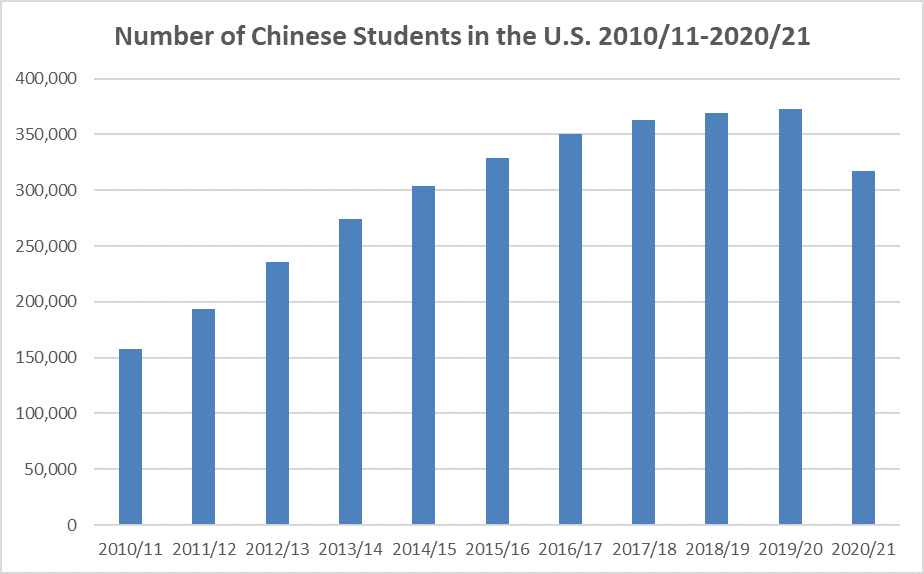

The fourth and final wave began with China’s most recent round of economic reforms. Driven overseas at least as much by a desire to avoid the aforementioned Chinese college entrance examination as by any wish to visit the Land of the Free Drink Refill, this most recent cohort of students is comparatively wealthy. Their predecessors may have been scholarship kids, but the present group is funded by their parents and paid (or has had paid on their behalf) more than $14 billion in tuition and living expenses in 2020. Such is enough money for America’s many glorified credential mills (er . . . colleges and universities) to become dependent upon it. The current crop of Chinese students in the United States is not as starry-eyed about overseas life as were those who came before them. Nevertheless, they have proven more than happy to trade whatever vestiges of Maoist-era modesty they have for American-style conspicuous consumption and buy the most expensive sports cars they can find.

It is this fourth wave that is now coming to an end.

Examining the events within each of these waves reveals several common occurrences and the inherent limitations of Sino-American goodwill building through higher education. Most obvious is the matter of the odd fit. Historically, American schools have been less successful at producing Chinese students who are well-adjusted to American life than they were at producing students who were maladapted to life in their homeland. This has been the case since the Qing dynasty (although such may be somewhat less of a problem today). Those who studied in the United States have on more than one occasion discovered that spending years in a foreign land with a different culture and values system from their own could come at considerable cost, financial and otherwise. And those who did not return—who chose to remain in the United States, have found that life as a permanent foreigner comes with challenges of its own.

Of the more than 317,000 Chinese students in the United States during the 2020-2021 school year, approximately 80% are expected to return home, a considerable increase from the 10% departure rate of 2001. This suggests that the Chinese who now study in America are less likely to be subjected to serious ostracism than were the sea turtles (those who, like their namesake, travel great distances but eventually return home) of generations past. The strength of the Chinese economy, disillusionment with the United States, and a concerted effort on the part of the Chinese government to increase patriotism all play their role in reversing China’s brain drain. And the number of Chinese students in the United States will likely peak in 2027 and drop steadily thereafter.

Comparing Cyclical Models, Making Predictions, and Other Acts of Tomfoolery

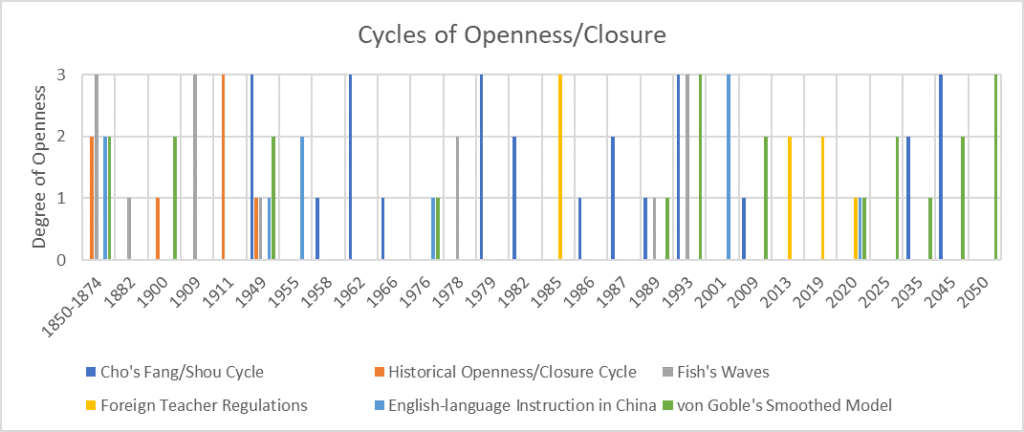

Cho’s fang/shou cycle, the larger historical openness/closure cycle presented in this section, educational market trends, and Fish’s waves of students somewhat overlap in time but differ in frequency. (The fang/shou rate of oscillation is decidedly higher than that of the others.) Visualizing their relationship is challenging without an illustration. Fortunately, an illustration can be had easily enough.

In the chart above, the numerical values along the y-axis indicate a discrete state.

0 = No data

1 = Closed state (minimal interaction with the outside world allowed)

2 = Semi-open state (some interaction with the outside world allowed)

3 = Open state (high degree of interaction with the outside world allowed)

This can be compared to the total number of Chinese students in the United States, which although along a shorter timeline, suggests an approaching period of closure.

This chart, based on data by Open Doors, evidences a trend of plateau and decline in Chinese attendance at American colleges and universities.

Cho predicts that the policies of President Xi Jinping will prove too repressive for the people of China and will inhibit economic growth. This will eventually lead to the rise of reform-minded politicians who will open China to interaction with the outside world. This pattern fits within his larger perspective of seeing the fang/shou cycle as being the result of competition between nationalist/conservative and reform-minded factions of the Chinese Communist Party. Cho may be correct in both his understanding of Chinese party politics and in his timeline. But one should note that his conclusions were published in September of 2020, before the second (and sometimes third) series of COVID lockdowns in China, the most extreme of which—Shanghai’s for example—lasted more than seven weeks. These lockdowns may be seen as evidence of excessive or unsustainable levels of control by the government. But the relative lack of protests, including in cities where food shortages were widespread, could as easily be taken as evidence of the success the Chinese government has achieved in cementing an unmatched level of control over its population. This control stands to grow stronger as China’s social credit and monitoring technologies mature, both of which are (to varying degrees) descended from the 档案 (dang’an) paper records system, which predates the Communist government.

Our estimate for China’s next opening (shown on the Cycles of Openness/Closure chart as von Goble’s Smoothed Model) relies on an averaging of overlapping datasets. In long spans where no overlapping data exists, an intermediate number was added except in cases where the political conditions in China had shifted so suddenly that interpolation of data would suggest a transitional state that did not exist. The chart has its imperfections, namely that different datasets are based on significant historical events, not samples taken at consistent intervals, meaning that some parts of the chart are slightly more chronologically compressed than others. Nevertheless, one can see general patterns emerge. One is that China has remained semi-open (state 2) more than it has been entirely closed (state 1). The other is that periods of complete closure rarely last for long. In all likelihood, the dramatic COVID shutdown of the last two years will not lead to long-term, complete closure. Instead, China is expected to partially reopen her borders by 2025, by which time normal air routes are expected to resume.

This does not establish that China will achieve pre-pandemic levels of engagement with the world. The number of Chinese students in the United States may peak by 2027, or it may never return to pre-COVID levels. This depends upon how much ill-will between China and the United States has grown over the last few years and how much the Chinese embrace Western technocratic education or return to their traditional Confucian educational paradigm. And the Chinese who attend college internationally may gain no understanding of (or appreciation for) Western culture, with many of them interacting little with their non-Chinese peers or the larger public. This is partially a result of language differences. It is also a result of values differences, personal preferences, the risk of being the target of hate crimes when straying too far from safe areas, and the chance of interaction with non-Chinese drawing the attention of Chinese and American authorities. The few brave souls who overcome these many obstacles may discover that Americans are quick to judge and condemn the Chinese ways of doing, living, and governing, based purely on mass media portrayals. Interactions of this sort reinforce the notion of China and her people being under attack and do nothing to engage Chinese students.

Considering the above, analyzing the data from Open Doors, and taking into account the probability that a supermajority of Chinese students in the United States after 2027 will return home, we can make a few predictions. The apogee of Chinese isolation will be from around 2030 to 2040, with the nation opening to outside influences gradually until 2050, by which time China will have entered a new era of engagement with the world. Trends in overseas education are but one factor included in the Smoothed Model. However, the tremendous emphasis in Chinese culture on improving the person both individually and professionally through education—a topic already partially addressed in this text and which will be touched upon again—makes it worthy of attention.

It is tough to make predictions, especially about the future. This difficulty is compounded by the comparatively rapid growth of technology, which is every bit as likely to reinforce and stabilize the Chinese Communist Party as it is to undermine it. And China, even after its great reopening, may never again interact with the world as it did in the 1990s and 2000s—an era in which China was still very much a comparatively underdeveloped nation. During this time, the United States and her allies could claim that liberal democracy and free markets were, if decidedly imperfect, the best humanity could offer in terms of governance and opportunities for happiness and prosperity.

The openness/closure cycle is unlike the periodic outbreaks of xenophobia in the West. To understand this difference, we must investigate the role of the people of China’s interior.

Coastal Action, Inland Reaction: An (Incomplete) Geographical Theory for China’s Openness and Closure

The role of inland China in slowing the implementation of the Hundred Days of Reform has been considered, and one should not ignore the political and cultural influence of the countryside throughout the 20th century and up to the present day.

Peter Turchin, the founder of cliodynamics—the mathematical study of history—has argued that revolutions come less from spontaneous acts of the peasantry than from elite overproduction. This—elite overproduction—is the generation of those who should be destined for positions of power (probably by virtue of their education, but possibly by inheritance of title) in excess of the positions available to them. If a society is to remain orderly for any length of time, it must both manage the expansion of the elite and rivalries between different factions of the elite. Traditionally, the meritocratic elite structure of China—the mandarinate—drew from throughout the country, relying upon a standardized body of knowledge that was national, not regional, in perspective and availability. It was also rigidly hierarchical, with admission to the upper ranks being extraordinarily difficult, and recruitment quotas being in place to prevent officials from any one region of China from dominating the structure.

The mandarinate was imperfect, which is not to say that it failed in its primary objective—maintaining stability and preventing a crisis of power concentration or elite overproduction for generations. The decline of its power and prestige throughout the last years of the Qing dynasty corresponded with the rise of a new elite who were Western educated, more engaged in global affairs, and decidedly less bound to the Confucian tradition. The tension that came into being between this group—with its aspirations of building a modern China—and that of those trained in the older tradition became evident almost immediately upon modern China’s founding.

Sun Yat-sen, widely recognized as the father of modern China, was educated in Honolulu and Hong Kong, spoke English fluently, traveled to Canada, Japan, and Britain, and was (possibly) an American citizen. And although his tenure as the provisional president of the Republic of China was short, he continued to be a major influence on Chinese political thinking throughout his life. Sun’s successor, commander of the Beiyang Army Yuan Shikai, was trained in the Confucian tradition (if not well enough to pass an imperial examination) and went so far in his retrogressive thinking as to entirely abandon democratic principles. He went so far as to declare himself the Hongxian Emperor (a title he held but briefly).

From the collapse of the Qing dynasty until the establishment of the People’s Republic, views on government and social progress, for lack of a better phrase, ping-ponged from the Confucian to the modern and back again. In everything from clothing to personal values to views on the rights of women, the country was in a state of flux, with the traditionally educated elites and their Westernized counterparts promoting different views of the future. The New Culture Movement, which advocated for the radical reform of every part of Chinese life—politics, written language, and religious beliefs included—was centered in urban areas and universities and consisted primarily of Westernized young people. The closely related May Fourth Movement, which was more focused on strengthening Chinese sovereignty and eliminating foreign control of Chinese territory, was supported by people with similar backgrounds and educations. There was considerable overlap, and some people actively supported both Movements.

It is not without consequence that the eventual leader of China, Mao Zedong was from a rural background but was educated in Communism. Communism is a Western philosophy that, depending upon how wide one believes the cultural divide between Eastern/collectivism and Western/individualism to be, seems to be better suited to the rice paddies of Asia than the wheat fields of Europe.

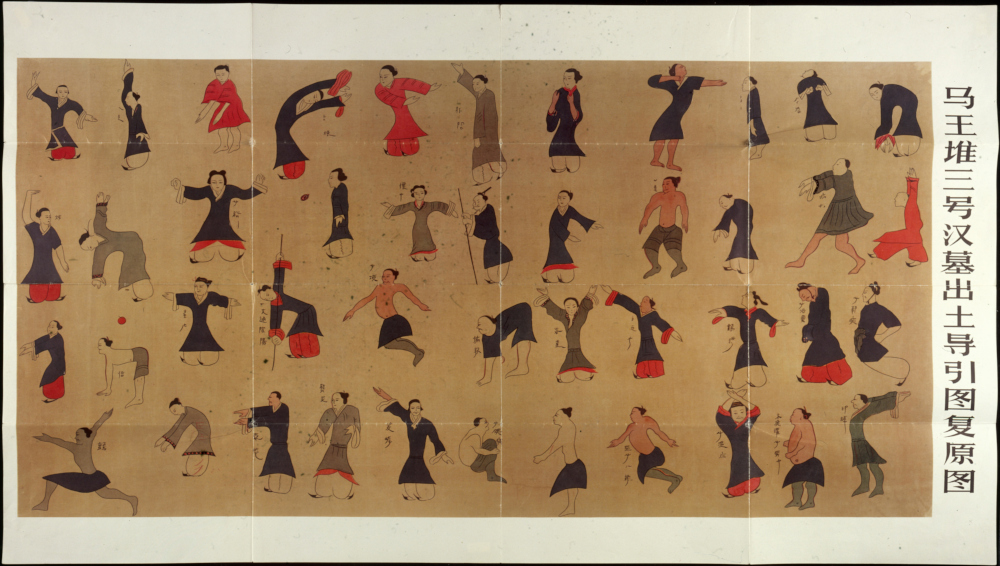

This wheat versus rice distinction is not merely descriptive, as differences in regional agricultural histories may affect the types of cooperativeness and innovation favored by a people. The farmers of the Chinese interior are unlike those of the American West and Midwest. American farmers demonstrated a willingness to work together when the need arose (barn raisings, funerals, and the like). But the need arises less often when one can rely purely upon local rainfall to water his fields than when his community must work together to manage elaborate canal and levee systems.

The values of the Chinese interior—that allowed farmers to work together in relative harmony for generations and that align them with Confucian thinking—are by necessity at odds with those of China’s urban areas. In the cities, where the impersonality of being one amongst millions fosters a certain obliviousness (if not complete indifference) to the lives and behaviors of neighbors and community members, individualism can grow, if not truly flourish. Where the bonds of community and extended family are weak, independence arises as a default. Periodic migrations from countryside to city serve to check the growth of such thinking. And this wave of traditionalistic/collectivistic thinking is in turn pushed back from the coastal regions by the tidal forces of foreign influence.

The described cyclical mechanism of balance is distinct from (if sometimes complementary to) the static equilibrium maintained by the mandarinate. And it has afforded China a resilience to Western influence unique amongst the Asian nations. This resilience has allowed China to mature technologically and economically (if slowly) while maintaining values and economic models radically different from those of the West.

Ignored Prophets and Broken Fingers: Getting Caught in the Closing Door

Much of the Maoist-era and present-day resentment of foreign influence stems from the Opium Wars and the imposition of the unequal treaties. The American impulse may be to dismiss this as ancient history, but this should be done with caution. Our eyes have beams of their own. A few Southerners are still sore over the Civil War, which concluded in 1865—more than 150 years ago. Considering this, arguments that the Chinese should forget their century of humiliation in less than half as long appear disingenuous, if not outright antagonistic.

Despite this checkered history, Chinese/American relations were never bound to eternal antipathy. For 80% of the last century, China and the United States were “allies, tacit allies, or constructive partners,” meaning that they had a functional, if not always cordial, relationship. And this relationship might have been better. John S. Service, a State Department employee who was born and raised in China and considered an expert on the country, predicted as early as 1944 that the Second Republic of China (the Nationalist government) would be defeated. He also correctly identified the incompetence and corruption of the Nationalists as a major cause of this failure. (That he failed to take into account the aforementioned historical development of China and how it primed the country for an agrarian mode of Communism did not make him any less correct.) For his foresight, Service faced the wrath of Senator Joseph McCarthy and a prolonged court battle to keep his employment in the Foreign Service—one that went all the way to the United States Supreme Court.

Had Service’s prediction been treated as a warning more than a betrayal, the American government could have worked to improve the governing abilities of the Nationalists (an uncertain option given America’s disastrous history of nation-building). Had that proven impractical, the United States could have exploited the eventually overwhelming differences between the Chinese Communist Party and the Soviet Union to build a working relationship with the rising regime. This would have required the American elite to consider the world outside the framework of ideology, which it seems capable of doing for the fascist right, but less so for any other group. One can debate the exact degree of harm or long-term benefit caused by Mao to China, but it is more difficult to support an argument with any historical evidence that his behavior was singularly atrocious. The American diplomatic and commercial apparatus should have had no trouble looking the other way—as they have any number of other morally questionable governments—for the sake of our nation’s interests. Doing so would have allowed them to cultivate a China less inclined to regard the United States with ill-will or hostility.

The point to all this: Despite the Chinese willingness to slam (nearly) shut their door to the outside world, the American elite have managed to get their fingers mashed but infrequently, and never properly broken. This speaks nothing to the latter’s credit. They (the American elite) are unwilling (or unable) to foresee the timing of such closings, even when doing so should be of trivial difficulty. Instead, this speaks to the pragmatism of the Chinese, who likely realize that closed doors may need to be opened again in time. Doing so is easier if blood and severed digits are not sticking to the frame.

But past performance is no guarantee of future results—as goes the world of investing so goes that of geopolitics. As the economic might of China grows, they will prove less predisposed to extend us the courtesy of overlooking our errors. And American interests will discover that the Chinese government, whatever its limitations, controls domestic corporations and corporate leaders and international organizations in its country fairly well. Businesses are expected to serve the people (in the government-as-proxy-for-the-citizens sense, not the satirical sense), rather than vice versa.

We should also bear in mind that a significant number of China’s closures were reactive more than proactive. If respected as a nation and civilization unto herself—not a subordinate demanding exploitation, redemption, or singularly unnecessary insult—China may well be engaged as a reliable trading partner and member of the global community. She should prove to be at least as willing to respect international norms, institutions, and boundaries as is the United States (with the last not necessarily being the highest of bars).

Knowing all this, we—those interested in learning both from China and how to work with her—can now consider some most pressing questions: Why are the Chinese withdrawing from the world? Why has China sealed herself off from outside influence and people in a way last seen in the reign of Mao? Has China simply grown hostile to the West as a matter of xenophobia and nationalism? Or is China’s closure part of a plan to avoid societal changes that, however ambiguously regarded in the West, appear as societal corrosion and decay to the people of a culture more concerned with harmony and cohesion than personal gratification? The answer may not be that the Chinese (tending towards insularity or not) know too little about us, but that they know too much.

America Against America/Knowledge Against Knowing

In 1988, Wang Huning won a scholarship to spend six months in the United States. Hardly unknown in China at the time, Wang was recognized as a rising intellect in the field of political science. Just three years prior, he became the youngest full professor at the prestigious Fudan University. And his writings were widely read and respected. Within China, Wang identified a decline in shared values and beliefs—a weakening of the collective consciousness of the Chinese people—as a potential cause for turmoil and decay. This decline was exacerbated by the considerable tension between traditional Chinese values, the modernist values of and around the May Fourth Movement, and the post-Cultural Revolution values of the Communist Party. He saw Communism—later, less severe iterations of Chinese-adapted Communism—as a third way, neither as ill-suited to the Chinese condition as Western individualism nor as hidebound to tradition (and incompatible with the requirements of industrialization) as Confucianism.

Wang supported Chinese Communism, but he did not hold the ideology and trajectory of 1980s China to be above reproach. He recognized that a hollowness in the culture—one that the social engineers of the day had been unable to fill—might become a reservoir of foreign or antisocial values if the Party did not take systematic action. And institutional reforms begun in the 1980s—which moved China away from a planned, centrally managed economy with lifetime employment (the iron rice bowl) to one of contractual, easily terminated relationships between employer and employee—deepened the void.

It is with his awareness of China’s evident crisis of direction and values that Wang conducted his tour of the United States.

Wang visited at least 30 cities and 20 universities during his brief stay—an average of one city every six days. Such is not long spent in any one place, but Wang was not interested in the specifics of any one place, but the common warp and woof of American life.

In his book, Wang is not blindly critical of the United States. Nothing in his text suggests that he hates Americans or that he wishes them ill, nor does he present the United States as an enemy to be destroyed. Rather, he alternates between admiration for the prosperity of the United States and curiosity as to the surprising degree to which life in America in that era was regulated. Regarding the first, he cites the impressive infrastructure of rural communities and the comparative technical sophistication of the United States, holding both as worthy of emulation. For the second, he notes the exacting requirements for pet rabies vaccinations in a community.

Beyond these superficial observations, there are some more salient ones scattered throughout. A few rise to the level of authentic insights. A sample of the many:

- Sexual liberation led to a weakening of the family, both by undermining traditional moral strictures and structures and by divorcing coitus from interpersonal attachment. This led to a rise in separateness¸ which itself led to an increase in divorce.

- Americans, those with families not much less than the rest, are often lonely. They are superficially friendly, but their relationships lack depth and durability. Mobility makes forming durable friendships, which is best done during the teenage and young adult years before one has a family, difficult. And American colleges, with their pick-and-choose options for course selection—as opposed to the cohort model of group course assignment—are poor environments for the building of long-term relationships. The young are segregated from the old, relationships are highly commodified (or monetized, according to Wang), and the workplace is ill-suited to anything other than instrumental interaction.

- American society is technocratic, with science and technology as the organizational principles of daily life. This is a strength and a weakness. Technology allows for the extraordinarily fine division of labor, and science and technology allow for degrees of individualism and choice that would be impractical in a less robust economy (as China was at the time). But Americans’ heavy reliance on science and technology, combined with their relative lack of other common values, has caused trusting the science (and scientists) to become a matter of faith, not reason. Wang considers this within his framework of futurism, which he defines as a willingness to invest in the impractical, especially in the defense industry and technology so that the future might be better. Other writers might see this as a trait of scientism—an unwarranted trust in science and scientists and their ability to resolve all problems. Wang argues that there is a tension between futurism and the traditional pragmatism of Americans, which addresses more immediate concerns. For our purposes, the best term for what Wang describes is technomania. This is yet another nonce word in this series (the first being omnipredator and its derivatives). It means love for (and fascination with) technology, tending to be based on an ignorant conviction more than informed understanding; a belief in technology as a magical force of problem-solving, rather than the result of human experimentation and endeavor. It is this—technomania—that causes us to believe that we can out-weapon any enemy and achieve improbable victories in impossible circumstances.

- America frequently fails her poor, drug-addicted, and disadvantaged, with homeless and desperation being prevalent in an otherwise extraordinarily prosperous society.

- Americans are ignorant of their culture, with little knowledge of either the Western tradition or the great works of the American people.

Wang makes note of other salient aspects of the American condition. Some of them, such as those regarding the problems faced by the Black and American Indian communities or the tendency of feminists to oppose the teaching of the classics, are difficult to dispute. Others, including his surprise at the homeless situation in the United States, are perennial, seemingly made by the Chinese of every degree of education or sophistication who spend any length of time in a major American city. And some were correct when made—the ubiquity of teen pregnancy and promiscuity in 1980s America—but are largely irrelevant to the United States of today.

Little of what Wang argues is wrong, and less of it is remarkable in its own right. To anyone who has read Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American (which was published a few years before Wang’s book, and which he references), almost everything Wang notes is profoundly obvious. More recent books—Bowling Alone by Robert Putnam, which addresses the decline of community, and Mary Eberstadt’s Primal Screams, which considers the relationship between sexual liberation and identity politics—contain better, more research-driven arguments for the essentially the same theories. Yet we should not dismiss Wang and his work as being without merit or consequence. There are no fewer than three reasons for this.

First, we should afford Wang his credit due. His stay in the United States was brief, yet he demonstrates a nuanced understanding of American life and thinking. Second, his book serves exactly its intended purpose—as a primer/introductory self-study course on the American way, suitable for those who have little firsthand with the United States or Americans. Wang’s writing may not be awesomely original, but textbooks rarely are, and what America Against America lacks in depth, it makes up for in breadth. Third, Wang’s book matters. The late Bloom was a cultural critic of a high order. Putnam and Eberstadt still are. But what (if any) impact, they have had on the United States, aside from serving as grist for the mill of endless and unproductive yammering, is uncertain. Wang and his book are a different matter. He is a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, which is a major accomplishment for an academic who did not rise through the political ranks in the ordinary fashion. And every bit as importantly, he has had the ear of three successive Chinese leaders—Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Xi Jinping. All had (or have) powers far more extensive than those of the President of the United States.

And when Wang spoke, they listened and acted accordingly.

What Wang saw as being fully arisen in the United States and emerging in China was a macroscale version of the crisis of meaning identified by psychiatrist (or anti-psychiatrist, as he is sometimes styled) Thomas Szasz. Szasz argued that this crisis is the root of what is now categorized as mental illness, which is itself a misnomer and a flawed (if socially expedient) way to categorize variations in behavior and thinking. Szasz’s position, much like that taken within this essay, is that the erosion of established values and accepted answers to existential questions—Why are we here? What is the meaning of life?—and their replacement with uncertainty is taxing. And it is even more so for the uncurious mind.

Szasz presents one possible means to lighten this burden: “more understanding, and appropriate action based on such understanding.” In effect, Szasz’s thesis is that the individual cannot go back to unsatisfactory answers of the past. Attempts to return to the allegedly halcyon of yesteryear will achieve nothing. However ill-planned the adventure of modernity may have been, the one way through it is forward.

As this applies at the individual level, so it does at that of the nation and her people.

The contemporary American strategy—common during Wang’s visit and more common today—is largely a combination of abandonment of the individual to his own devices (and the machinations of hucksters and abominations) and the medicalization of the human condition. The process of medicalization has led to the construction of what sociologist Philip Rieff described as a therapy culture. In such a culture, every form of mental and spiritual distress is categorized as an ailment in need of treatment, not a question of purpose to be addressed (if not always perfectly answered) through thought, examination, or philosophy. The convenient nomenclature of psychopathology permits the compartmentalization of every act, every pattern of behavior, and every person. And as Wang noted, the caregivers and professionally concerned—what he calls members of the welfare machine—those expected to fix our poor and damaged, are no more dedicated to their work than their employers require them to be.

Problems of scale and civilization become glitches of nerves. Our language is transformed from one of concrete discussion of problems and solutions, from God or meaning or philosophy to the absolutely personal. And this builds upon the American (and to a lesser extent, occidental) romance with individualism. Each man has his own excuse, his own ailment, and his own singular purpose—to heal himself or seek out those people (or drugs or occasional media products) that would do the same. Each woman’s distress is neurochemical or culturally imposed, but it is not her fault. Collective standards of conduct and value require collective agreement—tacit agreement at a minimum. Civilizations necessitate that we work together, but each man and woman can suffer alone until submitting himself (or herself) to the tender, infantilizing ministrations of helpful mother-tyrants. The last is exactly what Szasz warned would happen, and it is a singularly effective way to erode the rights and freedoms of the individual while claiming to protect them. Thus is paved the path to American tyranny—a tyranny of the worst sort, one that straitjackets the people but does nothing to arrest or reverse societal decline.

Wang was not (and is not) so restricted as are the increasingly roped and doped citizens of the United States. It is easy enough to destroy a culture through the promotion of decadence, perversion, and instant gratification. But building and maintaining a robust society is difficult without a strong hand. And a strong hand is what Wang and his government have at their disposal. When celebrities misbehave, they can be erased from public memory. If middle school and high school students are deemed to be in a state of spiritual or physical decline from excessive gaming time, the matter is addressed with a sudden, brutal urgency. If young men are found to be growing effeminate—a problem decried by many conservatives in the West (with some justification)—the government simply bans them from the media and institutes educational policies designed to make boys more manly. And if the extremist adherents of feminism begin to pose a threat to the social order, they are quickly shut down.

But a strong hand alone is not enough. For those with a love of power, these methods may seem ideal, and the ability to use them, the stuff of dreams. But such techniques have their problems. Used to excess, they almost invariably produce the opposite of their intended effect. More sophisticated, nuanced measures to stabilize a society and help in the construction of something new and sustainable—more guidance, fewer beatings—are available. And we will consider those later in this essay, when we conduct our investigation of brand and branding.

Not all of these initiatives are the work of Wang. But enough of them are either his initiatives or the products of those inspired by his philosophy and cautions against Western-style decline, that Wang can, if nothing else, be seen as their spiritual father.

Wang’s—and, by extension, the official—perspective on the West is more sophisticated than the schizoid (and consistent only in the extent to which it is ill-informed) China threat/China ally view promoted by Western media. The United States is neither a shining city on a hill nor a hellscape of capitalist decadence. She is a lesson to be learned, with some good elements, some bad ones, and some simply ill-suited to China and her people. Through Wang’s research and travels, the Chinese have learned something about the United States. And through their experiences working and studying in the United States and their exposure to Western media, the Chinese—the elite Chinese, if no one else—have learned more. They have learned more about us than they knew a few decades ago and more about us than we know about them. And they (or their leadership class) are choosing to pull away from the Western model of governance and culture.

The Chinese have an abundance of Western knowledge and knowledge about the West, and knowing what and whom they know, they seem to know that they wish to know us no better than they already do. To attempt a more Rumsfeldian phrasing (in case the prior sentence was not boggling enough): The Chinese elite know what they want to know about us. They know what they do not want to know about us. They know what they wish their people to unknow about us. And they know that which they do not know that they do not know is probably just as well left unknown.

What we should know is that the Chinese are no longer dependent upon us for knowledge of the technical, cultural, or economic sort. And as they have been intent to learn from us, so should we be determined to learn from them. The neo-authoritarianism and neo-conservatism (not to be confused with the American ideologies of the same name) of Wang and his cohort grew primarily in response to identified moral and economic weaknesses of 1980s China. Their designers also incorporated into them an understanding of the moral weaknesses and economic strengths of the West. Americans should strive for at least a matched level of understanding of China. We must do this so that we can understand the dynamic geopolitical situation and how to adapt to it.

Szasz’s imperative for more understanding may not always be applicable on the individual level. It, much like Nietzsche’s struggle of the individual against the collective, stands to be a great deal of work—too much work for those with less mental initiative. But such does not mean that understanding on the collective level and by those who wish to understand is an unworthy or impractical goal. As we learn about ourselves, so shall we be able to learn more about China. And as we learn more about China, so shall we gain a better, if indirect, understanding of ourselves.

Ultimately, neither the leaders, the intelligentsia, nor the ordinary citizenry of the United States have the same authoritarian tools at their disposal as do the Chinese political and intellectual classes. What we do have are sophisticated powers of storytelling and myth creation that dwarf those of the Chinese, who construct narratives comparatively slowly. National myth and national brand are critical to the survival and prosperity of a modern nation. The mechanics of national myth and brand development are examined in this essay, as is a sample application of brand development for the Chinese. How to apply these mechanics (and the national myths and brands they are used to create) to answer the existential questions facing the American people will be explained in Part III.

In the End, as in the Beginning, Everything is Myth: Defining the Chinese Nation

What is a nation? Wait a moment before turning to the dictionary. There is something to be said for constructing a definition of your own. A better (and easier to answer) question might be: What are the essential elements of a nation? Here are a few that come to mind:

- National boundaries? Those would seem obvious, even if they are sometimes imperfectly defined.

- Citizens or subjects, somehow legally defined and recognized? Without a population, there can be no nation.

- A military? Not all countries have them, but they would be the exceptions, and those nations are tiny, so who cares?

- A uniform and overarching set of laws? Such seems a sensible requirement, but what of international law? Can a country bound by laws beyond its making and regulation be considered truly sovereign? The United States government has argued in the negative, with this being one reason it has rejected participation in the International Criminal Court and questioned the legitimacy of its rulings. Six other nations—China, Iraq, Israel, Libya, Qatar, and Yemen—were also disturbed enough by this potential infringement of national autonomy to reject ratification of the Rome Statute, which established the supranational judicial body. The jury is still out on this matter of international law and national sovereignty (not that China or the United States would pay any attention to its verdict anyway).

- A common language? Even Canada lacks as much since the Official Languages Act declared her a bilingual nation more than 50 years ago. The importance of the less-used language (French) appears to be diminished by the day, for whatever that is worth.

And then there is the confounding matter of empire—the British Empire would meet almost all of the pertinent aforementioned criteria. But it was never a cohesive nation, and while many were subjects of the Empire, some subjects were more equal than others.

The problem with a definition by list is that it may be descriptively effective, but it is prescriptively deficient. It has no thesis. It has no articulated theme. A checklist may yield more consistent results than the “I know it when I see it” test once used by the United States Supreme Court to define obscenity, but not by much. And as one goes back in history, our checklist becomes less meaningful. For an ancient and relatively closed society, as was China, modern definitions of nationhood are lacking. An example: Before 1909, considerable uncertainty surrounded the question of who was Chinese (versus who was a non-citizen living in the country). The nation had customary law, which dictated that citizenship was passed from father to child, but left most other issues unresolved. Children of unclaimed paternity, women who married Chinese men but lacked certain citizenship of their own, and lifetime residents from other lands might have found themselves on an uncertain legal footing in the Celestial Empire. It is difficult to imagine a modern country allowing the definitive issue of citizenship—the most vital matter of who are our people—to retain this degree of nebulousness for any length of time.

China the civilization and China the nation are not perfectly overlapping concepts. The former predates the latter by thousands of years. And Chinese nationalism—nationalism in general—is a recent construct. One of the 20th century’s most respected sinologists, Lucian Pye, suggested that the distinction was of little relevance when he described China as a “civilization pretending to be a nation-state.” This may be an intuitively attractive description of the country, but it ignores the deliberate nation and national identity-building work of the last 120 years.

To determine when China became a real country—one as internationally relevant and legally evolved as any other—we must (paradoxically) turn to the realm of imagination.

Benedict Anderson and the Power of Language

Born in 1936 in Kunming, China, to an English mother and an Irish father employed by the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, Benedict Richard O’Gorman Anderson (professionally known as Benedict Anderson) was as much a man of many nations as one could be. Anderson was raised in California; educated at Eton, Cambridge, and Cornell; lived in Indonesia; taught in the United States; and spoke at least ten languages—Latin, Greek, French, German, Indonesian, Javanese, Thai, Tagalog, Dutch, and Spanish.

Most significantly, Anderson wrote Imagined Communities, which provides one of the most comprehensive, widely cited theories of the development of the modern nation. We consider Anderson’s peripatetic, polyglot life as more than a point of curiosity. His varied experiences informed his thinking in a way unique amongst Europeans and Americans. Anderson’s theory of nation creation was centered on language and shared, imagined (not imaginary) identity. How did he define a nation?

[A nation] is an imagined political community—and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign. It is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.

Benedict Anderson

In this way, the nation supplants the family, the band, the tribe, and the chiefdom with an abstraction, one in which the traditional bonds of blood, marriage, or interpersonal connection are of diminished importance. Humans have a tremendous capacity for organizing themselves into structures of size and scope that no other primate could imagine. Yet most of these non-family structures require some process of induction. Consider organized crime—the mafia, the triads, the yakuza. Family bonds may help one gain admission to these groups, and being of a particular ethnic or regional background may be a prerequisite, but mere family bonds or place of birth are not enough. Without taking the appropriate steps, one cannot become a member. Religious orders have rules of their own, as do corporations and other legitimate organizations. The nation is a peculiar construct. It is neither organic and biological in origin, nor is it truly an organization of free and voluntary association. Aside from naturalized citizens and those who choose to surrender their citizenship, the citizen is bound to country by accident of birth, yet blood may have nothing to do with the matter.

Anderson argues that the nation is a product, first and foremost, of vernacular language’s rise to economic and educational primacy. This occurred, according to Anderson, with the birth of print capitalism, which made the mass production of books profitable. The act of reading a text in one’s native language and seeing that language treated as a serious form of communication is historically novel. For the better part of history—up until Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of cast moveable type—books were too expensive for the average man to own. And the cost of producing books for the small market of a regional language—one which might have lacked a well-structured orthography or many literate speakers—made doing so uneconomical. Thus, the written word was a language apart from that of everyday speech for most. Only with the emergence of print capitalism could sufficiently sophisticated vernacular communication, communication that exceeded the strict limitations of individual human mobility and memory take place. And this—a common language that transcended the boundaries of class or region—is what allowed the shared discourse, culture, and values required of the imagined community to sprout and grow in the hearts and minds of the populace.

With language comes identity. The Latin-literate European elite who dominated their continent’s culture before the 20th century could regard themselves as members of a linguistic fraternity that, like the royal households, were more closely connected to each other than those subordinate to them. But the emergence of robust vernacular literature and culture changed this, as did the diminution of the notion of divine right.

The nation is a fundamentally new construct in that it—in practice, if not in theory—is egalitarian. The wealthiest man is no more American (or French or Chinese or Swiss) than the poorest, and what is celebrated as national culture is non-elitist by design. Consider the construction of national literatures.

Citizens of the United States may take for granted that there is a Great American Novel, as a category, if not an individual work. But why? The concept was not introduced until 1868—shortly after the Civil War. And it was curiously defined. The Great American Novel needed to be more than a novel that was great and (as one would expect) American. It needed to define a national character—the distinctive personality and behavioral traits of a country’s people—and the majority of significant American literature already published in the late 19th century was peremptorily excluded. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s works were dismissed as lacking a sufficient sense of character, place, and narrative—of not being American enough—whereas Uncle Tom’s Cabin was offered as a candidate.

If this seems deliberate, exclusive, and self-conscious, such is likely due to it being exactly that. Countries with their own language, one that is used little outside of their borders—Japan, for instance—have an advantage in this regard. Defining the boundaries of Japanese literature is easier than defining those of American literature, if for no other reason than that American literature risks being confused with that of another English-speaking people. An American novel could easily face accusations of being too British or (heaven forbid!) too Canadian.

A noteworthy component of Anderson’s thesis is that nationalism reached maturity, not in Europe (although the requisite print-capitalism did), but in the Americas. There, in South America first of all, the descendants of colonizers found themselves in a precarious position. Genetically and phenotypically distinct from the Mesoamerican peoples who constituted much of the population, they were told by the colonizing powers—Spain, Portugal, et cetera—to regard themselves as (lesser) subjects of monarchs they knew exclusively through print and proclamation. These kings and queens resided in homelands so remote that they might as well have been, if not on the surface of the moon, distant in a way that is nearly unfathomable in the jet age.

At its heart, nationalism entails a process of consolidation of regional identities. Anderson emphasizes the role of the creole pioneer—those who elevate (one variety of) the local language to the elite status. Who these are and where they live is a determining factor in which dialect of a language becomes standard and which others become provincial. In English, we can see this in our decidedly counterintuitive spelling system, which is essentially frozen in time and place—that time and place being late 15th century London, where William Caxton began operating England’s first printing press. And in France, the Francien dialect of French became the official language in the 16th century, relegating all other forms to inferior status.

But not all consolidation is linguistic in nature. The post-Civil War Reconstruction led to an expansion and redefining of Americanism, weakening the notion of state-specific identity and replacing it with a national one. A similar unification of identity happened in northern Europe when many small kingdoms that were formerly members of the Holy Roman Empire were forged into the singular state of Germany.