(Part 2 of 6)

Khiem—Kim, as pronounced by Elmer—is an odd duck. Not foreigner odd—she didn’t sound foreign when she spoke (which was not often) and Elmer guesses that she was raised in the States. She’s odd odd—no eye contact, flat voice, keeps counting spoons. Maybe she’s just terrified. People do strange things when they’re afraid. But that doesn’t explain the tent she set up in her room. Maybe she just wants her privacy. Or she thinks Elmer will be tempted to try something sinister if he sees her in a state of partial undress. On a different farm, her fears might be justified.

Regardless of her reasons, this stray isn’t getting too friendly. The ones who did usually stole something. And she was a good cook. Amazingly so.

Anyway . . .

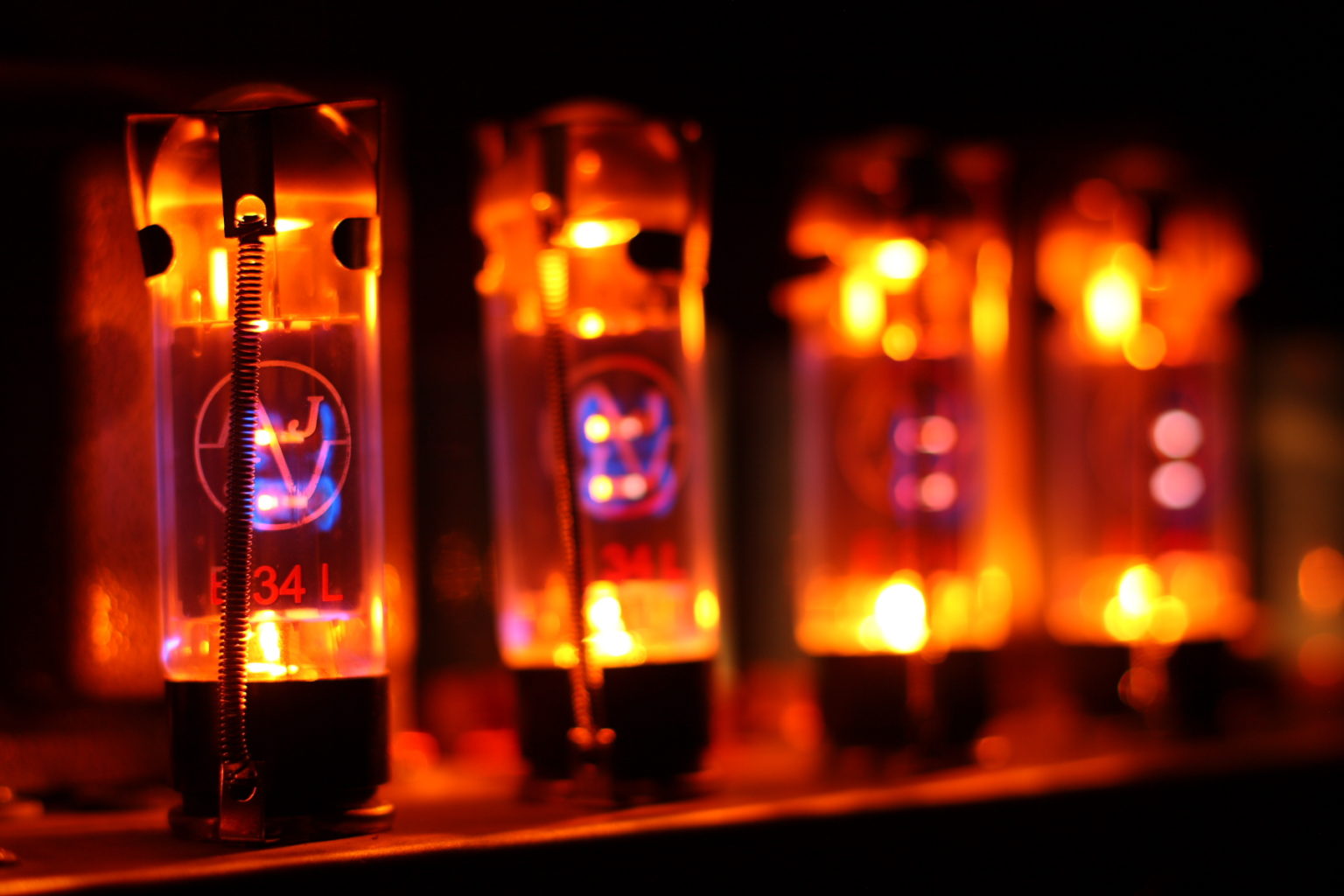

Elmer turns to the radio, a mess of wires and components he managed to find by scouring every abandoned house, every junkyard, and every partially gutted electronics supply house in four counties, soldered together with a finicky butane iron and crammed into a steel box. There are two directional antennas outside—Yagis cobbled together from scrap metal—aimed towards New York and California, respectively, and driven by an array of Sovtek vacuum tubes stolen (er . . . liberated) from a music store’s worth of guitar amplifiers.

Most of the gear is junk, really—everything except for the Vibroplex key—his money machine. Morse code is the only thing that works anymore. Everybody on the great net in the sky—a different sort of Skynet—can use it. Putting together a functional single-sideband transceiver would have been a challenge, with the resulting voice transmissions cutting through the noise of time and space far less effectively than Morse. And the duty cycles for AM and FM would have been too high for the pathetic equipment that formed the backbone of the new information dirt road. The generator is crap too, but it’s carbureted, which is the only reason it runs.

So Elmer powers up the machine. The tubes will need a few minutes to warm—just enough time for him to brew himself another pot of coffee, sharpen a few fresh pencils, and prepare himself for a solid eight hours of receiving and relaying messages from one coast to the other, and a few more sending out messages from locals to far-away friends and relatives. Occasionally, the senders got word back. But not often. The better part of the population seems to have disappeared into the void, unreachable by even the most determined operators.

How many people even know about the operators and about their relay network is up for debate. And not many people (operators or citizens) stayed at their city addresses for long—no food, no water, no fire control, no fun. A veil of ignorance had fallen across the world, and humanity was nearly back where it started. Information is cheap, until it becomes expensive. And then it’s priceless.

Which is why Elmer’s rates, no matter how absurd they might have seemed in the era before the storm, are entirely reasonable now. So Elmer is one of the richest men in town.

He considers asking Kim to fire up the stove again—about the only thing he hadn’t hated about Vietnam was the food and drink, the coffee in particular—and given her weirdly encyclopedic knowledge of the culinary arts, she would almost certainly know how to make a cup better than could Elmer. But she’s already retreated to her tent, and that deer-in-the-headlights look she keeps giving him is more than a little off-putting.

Elmer adjusts the hot incandescent lamp at his desk, pulling the light down to a tight cone over his notepad, leaving all the grimy wood paneling and war trophies of the office in near darkness—each and every photon is precious. He needs all of them he can get at his age. Elmer’s eyes reset again. One is inverting colors, and the other is reversing the image—like looking in a mirror. Great, just great! He reaches for an eye patch. He hesitates. Elmer isn’t certain of which eye is going to prove to be a bigger pain in the ass.

***

Phan Phat Trinh—Louis to the other guys in the band—and his wife don’t speak much on the walk home, not that Louis ever does. He had been warned about marrying an older woman—big sister, little brother romancesfailed more often than not—and this older woman was more challenging than some. Louis hadn’t wanted to barter away his daughter. The whole thing was the wife’s idea. Poor, innocent Khiem nearly bounced out of her skin at the slightest unexpected sound, and being asked to move a piece of furniture out of her room—an unfortunate necessity when the family had sold the better part of what they owned for food—reduced her to fits and tears. But what else could they do? They couldn’t afford to feed her.

“She’ll be fine!” The wife keeps repeating the sentence with so much conviction that Louis isn’t certain of whom she is trying hardest to convince. “The old man wouldn’t hurt a fly—a real softy. I know it! Besides, Khiem is our secret weapon!”

Looking up at the moon, in heavens wondrously unpolluted by the lights of man, Louis isn’t sure about this. You never knew what would catch Khiem’s fancy and what wouldn’t. She could learn at a remarkable rate on her good days, driven as she was by an obsessiveness that pushed the limits of human ability, but on her bad days, she’d curl up and wait to die.

The wife is drawing close—stomp, thump, stomp—Louis had never heard another woman’s feet hit the ground as loudly as do those of his wife. She could be almost silent when so inclined—those disproportionately large feet of hers could move with grace—but she was never so inclined around Louis. Perhaps she was once a secretary bird, and he, a snake or a lizard. One might assume that a single lifetime of kicking in heads would be enough, but only if one didn’t know this particular gal. She could keep it up for eons—through thousands of cycles of death and rebirth—and with a cheerfulness that might well defy all scientific (and most spiritual) explanation.

“Hey, you are running away!” The wife calls out to Louis in Vietnamese, trying to sound jovial when she says it.

Louis doesn’t answer.

She’s caught up to him. She could power past him, but she doesn’t. Instead, she merely keeps pace.

Louis likely misses Khiem more than Khiem misses Louis. Khiem seems to miss her routine more than anything else. But who knows? These female minds are essentially opaque to Louis: He doesn’t know what Khiem really thought or felt when he and his wife walked away, leaving Khiem with Elmer. Khiem’s expression, as usual, was impassive, her face a mask of apparent indifference, or anxiety, or frustration, or some strange emotion ordinary human beings would never be able to understand on even an abstract level, much less experience for themselves.

And he knows even less about his wife’s true take on the matter. The wife has plenty of expressions—her plastic, perpetually animated face; along with her never-ending liveliness and her slightly warped sense of optimism; had drawn him to her, despite her already being well beyond her prime by the time they met—but he doesn’t really know how much weight to assign any of them. He can never tell if she’s acting. The simplest operational assumption is that she isn’t, so Louis goes with that. And he’s lost too much already. He doesn’t have the heart to argue.

The pavement ahead is washed out. They hadn’t come this way—the main path was faster, but only a maniac would travel it unarmed at night—and neither of them had been down this road for months. Louis looks over to his wife. He wishes he had brought his rifle. Thieves sometimes hid in the ditches, at least that is what Louis has been told, rapists and murderers too. He thinks he sees something moving in the shadows. The wife doesn’t seem to notice.

***

People grow laconic when they’re paying by the word. Brutally, wonderfully laconic. There’s no more Why don’t you pick up more ice cream? Listen to me more! Weneedtotalkaboutourfeelings. Howmany boyfriendsdidyouhavebeforeme? Areyouabsolutelysureyouarentinfectious? Whataboutthewarts? ThelizardpeopleandJewsareresponsible . . .

Blah, blah, blah!

They might well carry on with this nonsense in meatspace, but on the relay net, all was elegance and directness.

Dad died Tuesday. Accidental gunshot. Oops! Best, Tim.

Jane had baby boy. Butt-ugly. Looks like neighbor. Jane infected. God help them. 🙁

The operators have more downtime than one might think, given that they are the last remaining reliable connection most people have with the world beyond the horizon, and the wait between messages is growing greater by the day. A few new stations pop up willy-nilly, but even more are disappearing—gas shortages, most likely. Some might get back online. Most won’t, not unless something changes.

So what’s an operator left to do? Shutting down for hours on end isn’t practical. Getting the generator restarted is a herculean effort, and there is no way to store and forward text when a step in the relay is down—paper for unsent messages accumulates quickly and delays are cumulative. Going to sleep isn’t an option: Elmer could miss a night’s worth of work (and income) doing that, and gossip amongst the operators is tedious.

But there’s weather. Weather and time.

Elmer gently removes his ancient Telefunken headphones, carefully gathering up the cloth-wrapped wires and placing them on his desk, and pushes back his chair, grabbing a pencil and notebook as he stands.

At the very edge of the cone of light are his targets. The first, a thermometer, hanging outside the window. The second, a rain gauge. The third—the only instrument inside the room—a barometer. During the day, he took measurements of wind speed and direction, carefully adding the information to his book, but he couldn’t do that after sundown. And there isn’t much of a breeze tonight. Elmer looks at his watch, closely calibrated to the old chronometer on his desk, and starts to write down the numbers.

Dit! Dit! Dit!

The time transmission has started: Elmer hears soft tones emanating from the headphones as his Seiko’s second hand sweeps past zero. Perfect. Perfectly synchronized.

Elmer shuffles back to the desk. Tomorrow, he’ll type up all the data, along with all of the telegrams to go out for delivery, on his West German Olympia. Might as well keep occupied, either that or die. Sooner or later he’ll figure out how to predict the weather. There’s a book on that around here somewhere.

Elmer thinks about the tent set up in the guest bedroom. He’d seen people return to the world—home, or what was left of it—with some peculiar habits. And he’s found that the best approach is to leave them and their eccentricities alone, so long as they weren’t hurting anyone. Kim might be recovering from something. Who knows? She might just be strange. Either way, she appears harmless enough.

Return next week for Part III, or buy Foresight (and Other Stories) today.

The Rules

The Rules is a philosophy and self-inquiry text designed to help readers develop mental discipline and set life goals. It does this by way of guided readings and open-ended questions that facilitate the rational and systematic application of each Rule.

Put another way: The Rules is a book designed to help men survive and thrive in the West.

Foresight (And Other Stories)

Four tales across time and distance. Always satirical and frequently dark, this collection considers the breadth of isolation and the depth of connection.

Brant von Goble is a writer, editor, publisher, researcher, teacher, musician, juggler, and amateur radio operator.

He is the author of several books and articles of both the academic and non-academic variety. He owns and operates the book publishing company Loosey Goosey Press.